“In the age of alluring, magical machines, a society that forgets art risks losing its soul.”

Camille Paglia

A stone in the shoe of many a hard line feminist, and the left wing sanctimonious elite, Camille Paglia critiques observes and opens up debate on a myriad of cultural topics. This isn’t to say that she carries a torch for the right, or feels any attraction to the centre ground either: her voracious propound essays on censorship, ‘sexual persona’ (Paglia’s groundbreaking barbed behemoth and antithesis to those hardliner feminist, whose summary riposte reads, “Art and pornography, not politics, shows us the real truth about sex”), and religion have fired broadside attacks on all sides of the political and ideals spectrum.

Rebuked and almost trashed out of history by her many detractors for the perceived threats that her ‘common sense’ conclusions on controversial subjects, have constantly fallen foul of the established rhetoric. Indecorous in the way that a native New Yorker, borne of an orthodox Italian heritage, isn’t afraid to lock horns and voice their opinions, the atheist gay feminist scholar has bloodied the noses of Naomi Wolf, Germaine Greer and Julie Burchill, to name just a few.

From the very outset Paglia has championed film stars (Elizabeth Taylor), pop stars (Madonna, well at least through the 80s) and the often put-down pop art of such iconic figures as Andy Warhol – who Paglia argues rendered the avant-garde redundant when he finally merged low and high art together – over the more traditional forms of theatre, ballet, literature and upper echelons of art.

Throughout she has, and continues to do so in this new book Glittering Images, lift these mass cultural idols to the level of their more established and snobby counterparts: Paglia has no time for the dry-laboured rhetoric and pomposity of the upper and middle classes camarilla that still dominates the arts.

Scornful of the education system in the USA, Paglia rails against, what she sees, is the negative impact that both postmodernism and post-structuralism have had on modern art and history, which she believes strips away the linear connections and concomitant narratives from these disciplines, isolating key events and theories from their wider context and relationship. But this ‘bite-size guide’ is not only for the student, its true aim is to re-asses and start a greater debate on the importance of art and the spiritual, transient magical experience it can give the viewer.

Paglia begins with a manifesto forward that lists all these many gripes, starting with the digital age, which she believes is overloading the viewer, allowing little pause to examine or study the relentless cycle of imagery we’re fed daily. By no means a luddite, Paglia welcomes the onset of technology, yet she advises extreme caution: “Culture in the developed world is now largely defined by all-pervasive mass media and slavishly monitored personal electronic devices. The exhilarating expansion of instant global communication has liberated a host of individual voices but paradoxically threatened to overwhelm individuality itself.”

The clarion call is for a rebalance in the way we see, and for self-education, eliciting that it’s time to wrestle back art from the elite, despite and because of the ongoing cuts to the creative arts and stranglehold by the privileged.

She chooses 29 exemplary images from the last 3000 plus years, each accompanied by a short historical/contextual essay. Certain synonymous Paglia opinions and traits are repeated through the featured wall paintings, sculptures, architecture and site-specific works.

The journey sets-out, quite literally, with a semiotic explored dissection of Queen Nefertari’s travail through the Egyptian afterlife (from a relief in her Luxor tomb), and stops off in ancient Greece (‘Charioteer Of Delphi’, ‘Porch Of The Maidens’), Renaissance Italy (‘Laocoon And His Sons’, Donatello’s dishevelled ‘Mary Magdalene’) and the modern era.

Why some inclusions may surprise and compound many, Paglia’s forthright and stubborn manner is very pervasive, especially when arguing the case for George Lucas’s Mustafar-set lightsaber duel from Return Of The Sith.

Aware that video games, digital movies and televised sport have more energy and appeal than post-modern art, Paglia’s belief in the imaginative innovations made by the director can be a little tenuous.

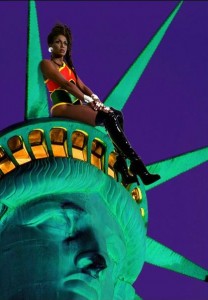

Regardless, she sets out a positive and engrossing biographical-laced case for Lucas; admiring his embrace of technology to craft an expansive, self-mythological world that’s managed to touch and enthral millions around the world, appealing to every culture. This inclusion speaks volumes about Paglia’s denunciation of modern art itself, which she feels has little to offer other than its reliance on past art movements and shock – She has signalled-out the lavish money-art of artists such as Jeff Koons and Damien Hirst for the biggest vitriol, whilst the infamous ‘Piss Christ’ photograph by Andres Serrano is deemed childish – Paglia maybe an atheist, but she often feels compelled to denounce attacks on the Catholic faith. In fact only one artist from the last thirty-years, Renée Cox (‘Chillin’ With Liberty’), makes the list.

Despite Lucas’s omnivorous nature to borrow (The Jedi is itself a quasi-mix of eastern religions and Taoism, whilst RSD2 and C3PO are based on Akria Kurosawa’s buffoon peasants characters from his film Hidden Fortress), and that most fans of his Star Wars franchise remain hostile in part to the prequels and lumpy laden dialogue, the emotive fantastical Mustafar scene is indeed a most diaphanous and explosive visual treat that alludes to Dante’s inferno.

Incredibly well written and researched, the selective ‘Glittering Images’ are a launch pad for philosophical and educational debate: the burgeoning voice and emergence of black artists in America is discussed by the work of John Wesley Hendrick (‘Xenia Goodloe’) and Cox; and the portraitist to the Great Gatsby jazz-age, Tamara de Lempicka, is given a respectful overhaul by Paglia, who believes that her glamorous nature and carefree spirit has shrouded the painters talent to capture the times but also reference the great masters via the Art Deco style – a style that because of its traditional adoption by the far right is often sneered at and left out of art history by “leftist resistance”.

However, I’m not entirely sure that Paglia’s guide will reach the desired audience, or have an effect on anyone other than the converted. And though I’m well aware that this digestible spread can’t hope to please everyone – it would be fatuous to list the catalogue of missing luminaries (nothing from any British artist) – it does at least throw-up some insightful erudite summaries and conclusions; explaining the development of performance and installation art and covering a wealth of movements from the impressionists to the abstract expressionists, shedding new light and useful observations on art works we’ve grown blasé towards.

Out Now

[Rating:4]