Nothing about the 1990s could have been so quintessentially British as Britpop. The clue, no doubt, is in the name. Britpop did more than just respond to its surroundings: it created them. The Oasis-Blur conflict of 1995 (memorialised now as some kind of local Desert Storm) lent an NME-friendly face to the North-South divide and re-garbled a familiar question: what exactly is happening to our class system? Meanwhile, the happy-go-smiley sop of bands like the Boo Radleys and Dodgy provided a domestic comfort that stood in direct contrast to America’s ever-growing assimilation of ‘counter-culture’ (fuck you, I won’t do what you tell me) into the fashionable norm. In a dark corner by the loos, whistle-tooting Madchester, gurning ecstatically from the Haçienda outwards, quite literally reshaped the face of the British party scene. But, for a decade that exported ‘Britishness’ in a way that hadn’t been achieved since the 1960s, ‘Cool Britannia’ emblazoned on the Union Jack like esoteric slogans at an away match, it was also a decade where not everybody was sure who exactly was British, and who wasn’t. In Northern Ireland, a series of failed ceasefires showed the world that outside of Kuwait and Bosnia, warfare-in-the-streets was still very much a Western pastime, even in the land of the Cool. For the talents of our beloved ‘Norn Iron’, the 90s would be a period of self-definition surpassing anything that the music media would drum up on the mainland, and would have an effect on the Britpop bubble in ways no one could have expected.

After the international explosion of Van Morrison in the 60s, the willy-fiddling grease of The Undertones in the 70s, and the transcendental fuzz of Energy Orchard in the late 80s/early 90s, many of the sounds that would shape the future of Britpop had already migrated from the Protestants’ corner and were seen wandering the North of England. Bands with their roots stuck firmly in Northern Ireland, such as D:Ream and Ash, were already gigging and recording. But the most unexpected contribution to the age would draw from none of these, nor even from the Troubles themselves. It would be immaculately-conceived, finding its roots in literature, tailored suits, French cinema, the eighteenth century, Noël Coward and the stiff upper lip. It would subdue the hard-to-swallow theatrics of Morrissey and Pulp and infuse them with a subtle, public school humour that released the apolitical potential of Northern Ireland at a crucial stage.

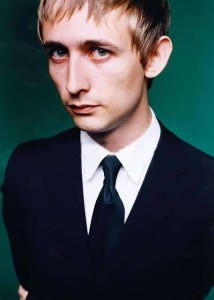

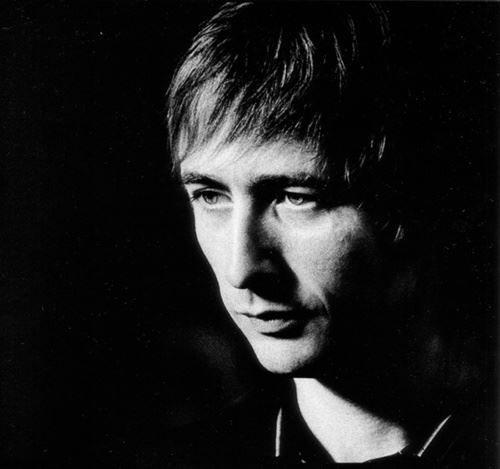

In 1993 (the year Professor Cox’s boys encouraged us that Things Can Only Get Better), The Divine Comedy – the schizophrenic nom de plume of Derry songwriter Neil Hannon – let loose the seminal Liberation album, a title that does as much to realise the artist’s libertarian attitude as it does his role as the fop’s own Lazarus. It flew neatly under the radar, perhaps because of Hannon’s retroscopic image as a literary crooner, or else because the album’s incessant references to dead authors (from Fitzgerald to Wordsworth) didn’t do enough for the class-sensitive masses. It wasn’t until Casanova [1996], and the success of its first single Something for the Weekend (buffered by tangerine TFI Friday furniture Chris Evans), that The Divine Comedy seemed suddenly relevant. The single is a timeless one, an immortal masterstroke of the tongue-in-the-cheek, and yet, one that settles so perfectly into the development of Britpop that it could be likened to a Bakewell cherry. Against the backdrop of The Lightning Seeds’ Three Lions, Jarvis Cocker versus Michael Jackson, and Oasis at Knebworth, Something for the Weekend lends Britpop an intelligence that legitimises its humour, a melody that validates catchiness and a frank awkwardness that celebrates the British way.

The Manchester Bombing of the same year might have provided an ideal cue for political expression, but The Divine Comedy chose to remain dandy. A nod to the conflict was left until the century-closing Fin de Siècle [1998], appearing only deep within the shadow of the band’s truest commercial success, the ‘only one they know’: National Express. The hook is still hummable by almost anyone alive at the time (normally not without a sense of irony), but it would be unfair to dismiss this rabble-rouser of a tune as simple cheese. It belongs in fact to a very special kind of cheese: a cheese of quality, an epoch-making cheese, a fine accompaniment to the rich Beaujolais of the region’s more sombre endeavours. The tightrope of the Romantic and the slapstick (that Hannon has not always kept in perfect balance) was an important alternative to the macho-istic ‘everyman’ model of some of Britpop’s leading frontmen – an alternative that went hand-in-hand with the young auteur’s political ambivalence. It drew from pop what needed to be drawn, and from Britain those aspects of high culture that we should never, as a nation, be quick to ignore.

Britpop had its time and place and, as it evolved out of itself, Northern Irish bands influenced by its grandiose presence found more success than ever. Bands like Ash and Snow Patrol, rising from the corrupted legacy of the Cool Britannians (and whose careers have run simultaneously with the peace process) have continued the personal, apolitical motif of music for music’s sake. As for The Divine Comedy, the albums following the turn of the millennium have continued to impress, exploring tragedy and comedy in equal measure and ploughing a persistent (if cult) route through the course of British music. Hannon’s osmosis into popular culture through Father Ted, Tomorrow’s World and the I.T. Crowd (theme tunes all drafted by the ‘bright young thing’ himself) means that the artist’s relationship with the general public may always remain a subliminal one. Fans have been waiting for a new album since 2010 whilst Hannon’s pursues his whimsical and essentially irrelevant project The Duckworth Lewis Method, and eventually, it will arrive. In the meantime, The Divine Comedy of the 1990s, running side-by-side with the comfort and controversy of the Britpop proper, is definitely deserving of a rediscovery. The pomp, the delicacy and the depth of those early albums provide us with some of the most unashamedly-sumptuous pop songs of the entire decade and cement Northern Ireland as not just contributors to the Britpop movement, but pioneers.

Relive Something for the Weekend here:

![Book Review: Blue Book One: Dreamhouse [Blue Tapes] 33 Book Review: Blue Book One: Dreamhouse [Blue Tapes] 2](https://www.godisinthetvzine.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/dreamhouse-cover1-150x150.jpg)