The discovery that it was free to borrow films from our university library was (ignoring the literature, those friendships, that first parentless leap into the social unknown) a discovery that opened up the depths of history like an estuary into an uncolonised continent. That is how I felt, something like tugboating into the Heart of Darkness, as I entered the jungle of international cinema. Being twenty-one years old, pretentious to the point of parody (which may not have worn off), with all the cultural confusion that follows that horrible moment when teenage rebellion finally dissolves itself, it was no accident that I was ensnared by film noir, Werner Herzog and, most revealingly by the Nouvelle Vague: Truffaut, Godard, Melville. But there, on the edge of that particular seduction, just outside and slightly ahead of the Cahiers du cinéma avant-garde, was a French director who offered the most personal relationship: Louis Malle. At twenty-one, standing at the precipice of working life, staring dumbfounded into the void of the future, Malle’s Lift to the Scaffold [1958] was both a pleasure and a parachute.

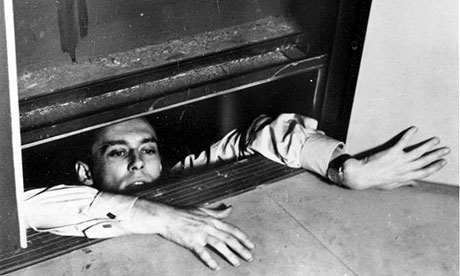

As the Guardian pointed out this week, Lift to the Scaffold is pure, distilled Francophilia. The nightlife of 1950s Paris shimmers under the insomniac glare of its clubs and cafes, blinking epileptically in the face of broken lovers, postwar strays, the débutantes and the damaged. A Hammett-esque locked-room murder motif is encircled by the aspirations of its hero-villains, sympathy intertwining with insecurity, masculinity with fear, escape with its ultimate impossibility. The austerity of lead Maurice Ronet (later to captain Malle’s Le feu follet [1963] with the same severe rigor) acts as a perfect mirror to Jeanne Moreau: the icon of beauty pushed too far, the dame archetype appearing baggy-eyed from scene one, stunning in the very composition of her face as she wanders the Champs-Élysées. Hints of the unrest that would surface on the streets of Paris ten years later find in Lift to the Scaffold some early exposure: the ghost of post-colonialism, the business of war, a reticence to surrender, acceptance of fear of the State, the psychologies of Cambodia and Algeria. Violence provides a shortcut for class ambitions, but as for the hero trapped throughout the film in a broken-down lift, when violence unbalances the system (the same system that simultaneously demands class stability whilst defining people by the cars they drive) even the loaded dialogue of a lover is a misfire. For the first time onscreen, the double-edge of Paris’ timeless Cool (as supported in a genuinely ground-breaking way by Miles Davis’ original improvised soundtrack – the first of its kind) appears side-by-side with its peacetime guilt. (Louis Malle funded his production company with money from his family’s colonial sugar business, and its ‘hazy’ links to slavery, as the Guardian have pointed out unglossed, as if mandatory trivia). Lift to the Scaffold is, beyond a stylistic jewel, a subtle evocation of how Paris was (and, cinematically, still is) a place infused with dreams, not just in the playful reverie of his Zazie dans le métro [1960] but as a kind of Yoshiwaran fantasy-construct (see what’s left of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis [1927]) where the illusion of action as divorced from consequence must always, inevitably, come crashing down.

With Miles Davis driving from the sound booth (through a single overnight recording session of untold significance), Ronet and Moreau dripping with desire shot-to-shot, and Malle’s cinematographic nuances shaping a monumental potential for the coming Nouvelle Vague, it is a surprise that the director doesn’t enjoy the same auteuristic credibility as Godard or Truffaut – especially considering they were all commercially successful at the time. Regardless, the importance of Lift to the Scaffold, as well as Malle’s other early ventures (Les Amants [1958] and Le Feu Follet [1963] – both masterpieces), is rarely understated and will always (as long as the lot of them are available to tight students with an inclination to pretension) remain in a state of perpetual rediscovery.

Lift to the Scaffold is playing in cinemas throughout February and March; the trailer and a full list of screenings can be found here:

http://www.bfi.org.uk/whats-on/bfi-film-releases/lift-scaffold