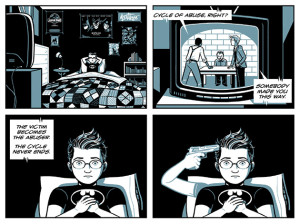

Trigger Warning: This interview deals in parts with issues of abuse. Please read at your own discretion.

In the comic book world, Dean Trippe is what you would call a comic book artist’s comic book artist. His work is highly stylised, recreating classic characters and scenes from the cornucopia of comic book lore, and casting a knowing glance (or pen) at industry tropes. However, as evidenced in Trippe’s extremely personal collection of comics, “Something Terrible”, he’s also using the art form as a form of therapy, bringing catharsis to a series of childhood events that would leave most of us psychologically broken. We caught up with him over email following a successful Kickstarter project that will finally see “Something Terrible” brought to print.

Whose comics are you reading at the moment?

I’m keeping up with Scott Snyder and Peter Tomasi’s Batman titles, and a lot of Marvel books. I thoroughly enjoyed Kieron Gillen and Jamie McKelvie’s Young Avengers run, and I’m into Jason Aaron and Ed McGuinness’s Amazing X-Men. Looking forward to Jason Latour’s run on Wolverine and the X-Men. Kurt Busiek’s Astro City is probably my favorite superhero title, because it’s so unlimited and cohesive. A few other titles I’m digging: Ms. Marvel, Batman: Black and White, anything with Miles Morales Spider-Man, Hawkeye, Daredevil, All-New X-Men, and Greg Pak’s Action Comics has brought be back around to liking Superman, even in this weird, half-rebooted continuity.

Your kickstarter just got funded. It must be an exciting time for you. How does it feel knowing that you’ve affected so many people with your comic, Something Terrible?

It’s a pretty wide range of emotions, to be honest. I was on a pretty big high for a while there, feeling like I’d done the most Batman thing I could possibly do with my set of talents and personal trauma, opening up about being sexually abused as a child, using comics as a medium to expose the only secret I’ve ever really kept in order to help others process similar experiences. Now, after the Kickstarter, I’m feeling overwhelmingly humbled by the response. I knew I was making a decision that’d change my life forever, that I’d always be tied to this topic that is so personally horrifying, but that it was worth it in order to DO SOMETHING to make a difference for other people walking around with the same secret memories and fears. And it’s happened.

For a little while there, I felt like Batman, though, like I DID IT. Now it’s running on its own, spreading every day to more and more people who desperately needed to know that they could put down their invisible guns. It feels different. It’s difficult to articulate outside of my nerdom, so here are two analogies: In order to tell the story and run the Kickstarter, I needed to adopt a mental image of feeling bulletproof. Now I feel kind of untouchable, intangible. Haha, I had to be diamond-strong Emma Frost to do this. Now that it’s done, I’m like Kitty Pryde. I don’t need to deflect anything or project an image of strength, anymore. While I was doing all this, I was wearing all black and gray, superhero shirts every day. Now I’m back to my secret identity, just a mild-mannered farm boy in glasses and plaid.

Like most media embraced by younger generations, comic books tend to be frowned upon (historically, at least) by both the older generation and the so-called artistic community. What do you think has changed that in the last decade or so (if it has changed at all)?

It’s been through some cycles. Comics used to sell in the millions, crossing all genres, read by children and adults alike. But, yeah, by the time I was growing up, even other kids looked down on comics. I remember trying to explain it to my buddy’s girlfriend in seventh grade. Everyone likes art. Everyone likes literature. These are respected. But comics put them together, and lets each carry the part it’s better at. And superheroes, my favorite genre, come down to the basic idea of using all of your abilities to help everyone you can. That’s the best thought humanity has ever had. Imagine a world of people living with that simple code. Just whatever skills you have. Just whoever you can help. That’s it. You don’t have to save the world, you don’t have to wear a cape, just do what you can, as well as you can.

This last decade has brought a shift, I think, as superheroes left the deconstruction era of the mid-80s to mid-90s, and entered the reconstruction (though there are plenty of holdouts still cribbing sad superhero stories from Frank Miller and Alan Moore), with guys like Grant Morrison, Kurt Busiek, and Mark Waid. Heck, even Moore was telling uplifting superhero stories with ABC Comics. The return to letting superheroes be super, letting them be what they say they are, rather than trying to drag them down to our level, that was the coming-of-age era for a lot of the hot writers now, which are informing the Marvel films, which are cultural touchstones for people outside of hardcore nerdworld. We’re in the era of the nerd, though. If you ask elementary school classmates of the President of the United States what they remember about him, it’s that he was the kid who could draw Batman and Spider-Man.

In just their first few years, superheroes infected popular culture, but now dominate it, thanks to poor artists and writers co-creating, revising, adapting, reconceiving, redesigning, and remixing them for three quarters of a century, across every medium. I think it’s a fairly progressive cultural movement, honestly, always forcing this American mythology and all their iconography to stand up for what we’re supposed to be, especially when we aren’t. Our greatest fictional heroes, created by children of Jewish immigrants just before and just after WWII. It makes so much sense. They’re infused with the belief that anyone can rebuild themselves and find a way to make a difference in their community using their specific talents. I swear, man, these are the best stories we’ve ever told ourselves. The global, cross-demographic audience superheroes now enjoy is a good sign for the future.

Something Terrible is an incredibly personal tale. How hard was it to share that part of yourself with the world at large?

It seems like it would be tough, and there were certainly pages that took me longer to deal with the emotional feedback the images generated. When I figured out what Batman said in that scene, for example, I just cried forever. I haven’t stopped. Of course he came to save me. He’s Batman. But the moment that took the courage was just deciding to do it, about a year and a half ago, now. I’d wanted to find a way to talk about it, to give other victims a look at how my experience of processing and rebuilding and eventually being freed from that nightmare, felt to me, but once I knew it had to be a comic, that, OBVIOUSLY, I had to use the skill I’d been developing for nearly as long as I’d been dealing with that pain, it was mostly downhill from there. I know where I was when I decided. That me was the one who made the decision. I’m proud of that me, because I didn’t know how this would go AT ALL.

What was it about comics that appealed to you over, say, books or movies?

I’m an avid reader and a huge fan of film, because more than anything, I like good stories, told well. The medium is almost incidental. But I will say, there’s something so special about comics. Comics have the one-to-one feeling of books, it’s just the storyteller(s) and the reader, working through each page at the pace of the reader. Morrison describes it as a hologram, and I like that a lot. Every reader has a personal experience, combining the images and words in their head, co-directing the pace, subconsciously creating passage of time between panels. Comics also have the ability to create even more unlimited visuals than film, with no budget. Film is only now catching up to the ability comics have to show us our best ideas from fifty years ago. But the static image also has a power film doesn’t. The directors and editors of films are completely in control of the pace, but the ability of the comics reader to pause and ponder the meaning of each visual is unique to comics. Again, I love all these media and others, but comics give us visuals novels don’t and the personal, text-based, silent experience that film doesn’t. Film and novels do things comics can’t, too, of course.

There’s also something so democratic about comics that I adore. Anyone can make one. People often ask me how to get into comics, and the answer has always been and will always be: make one. You could be a comics creator today. Just make a comic. I started doing single panel cartoons in third grade, comic strips in fourth or fifth, multiple page stories in seventh, and my first full comic in eleventh grade. I was surprised when I got to art school to major in sequential art and found other student who’d never made a comic. The only difference between a comics creator and a comics fan is the creating part. We’re all fans. You’ll need something to draw on, and something to draw with, but that’s about it. You barely even need an idea. Just draw what you did today. Done. You’re in.

You identify a lot with Batman in the comic. Can you tell us why?

Maybe. I mean, it’s a lot. I always felt like Batman was my guy, because he was a child who decided not to let his tragedy define or break him, but instead set out to rebuild himself into someone who could’ve saved himself that night, and use those skills to help everyone else. It’s not guilt or revenge or whatever else creators like to impose on Bruce. He needed something that night that didn’t exist, so he became that thing. A superhero. He wrapped himself in the darkness he feared, and set out to wage war on all those who would threaten the innocent. It’s religious for me. Bill Finger’s Batman origin story is seriously the best story I’ve ever heard. I love his friends and family, I love how his rogues reflect broken mirrors back at him, showing him the easier paths his trauma could’ve taken him down. But lately I’ve been thinking about why it was Batman over other heroes, and there’s a new thing I realized about him. Batman’s a character who could appear in a story and save a kid from being abused in any form. It’s hard to tell that story with Superman or Spider-Man. You could do it, but it’s almost like the crime in my own secret origin is too dark for them. I know those guys are big enough heroes to save us, and keep saving others, but Batman, being grounded in more of a real-world criminal setting—as much as I love seeing him in space or time traveling—Batman was born of a horrible crime, and fights crime in a city riddled with dark crimes. Those crime scenes can’t tarnish his boots the way they would Superman’s. He knows how broken things are. He’s not hopeless, he’s making a difference, he’s saving the world on a regular basis, but he’s capable of true empathy with every victim, and even though he feels all the pain, he never, ever stops. Batman is something else, man. He’s not an anti-hero. He’s an eight-year-old’s idea of what the world needs. And it really, really did.

Which Batman story series would you say affected you the most?

The 1989 Burton/Keaton Batman flick is what hooked me. I’d been a fan of Batman as much as any kid, but that’s the one that gave me his origin, which felt so familiar to me, as a victim of childhood trauma. I’d say the stuff that most informed my understanding of Batman, though was Paul Dini and Bruce Timm’s work on Batman: The Animated Series. In comics, Chuck Dixon and Grant Morrison did the most stuff with the character and his world that have kept me locked on for so long. In middle school, I used to carry around Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns in my backpack like a bible, though. I think a lot of people have their own interpretation of that story. For me, it was about this: Batman is incorruptible. You can join the mission or get out of his way. Even if you’re his best superfriend. Batman can’t even lose without winning.

There’s a new generation of artists and writers out there who clearly started out on the road as fans themselves (Moffat and Gattiss spring to mind, with their work on Doctor Who, as well as Kevin Smith, Joss Whedon and J.J. Abrams who appears to run the Galaxy these days). What advice would you give for anyone who wants to follow in their heroes’ footsteps?

Get into it. Work on all the elements of the craft you want to be a part of and tell your own stories. That’s what those guys did.

You’ve got a very distinct style, which brings to mind 50s Americana. Can you let us know which artists you drew inspiration from?

Yeah, I was drawing Butterfly for a few years before my friend Vito Delsante pointed out to me that I was basically doing Silver Age comics and didn’t know it. The biggest influence on my art and writing was Batman: The Animated Series, which was obviously modeled on and influenced by more classic and retro styles. My favorite artist of the Silver Age is Wayne Boring, who had a huge impact on the look of the character, and drew in a beautiful, clean style.

Finally, catharsis, or at least escapism, seems to play a big part in your work. What do you have to say to anybody who might feel trapped in a similar situation to the one documented in Something Terrible?

If you’ve got an invisible gun to your head, put it down, and try on one of these invisible capes.

https://twitter.com/deantrippe

https://www.facebook.com/ilikedeantrippe