It’s funny how so much of the music we listen to, which marks out whole episodes of our lives, becomes meaningless with time. With all the renewed interest in 1990s shoegaze bands, perhaps thanks to the return of Slowdive and Ride, it’s made me critically reappraise the bands that shaped my late teens. Unsurprisingly, most of it doesn’t really stack up anymore, at least not in the way it did at the time. But there’s always one album that cuts so deeply into your adolescence that it will take you back there every time you hear it.

For me Pale Saints debut, The Comforts Of Madness embodies the boundless energy, hope, fear and chaos of finding a way through that period. Pale Saints ‘split’ in 1993, after second album In Ribbons (or rather, founding member Ian Masters left and they carried on, with Lush‘s original vocalist Meriel Barham). It inevitably ushered a new musical direction for the band, sadly lacking all its previously dark, warped arrangements and Masters’s fallen angel vocals.

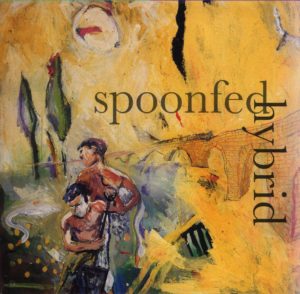

However, this break up made possible an enduring favourite album of mine, Spoonfed Hybrid‘s self-titled debut, from November 1993.

I was studying in Amiens, France, having a miserable time, when the album was released. I first heard the unmistakeable opening track ‘Heavens Knot’ late one night on a local indie radio station. Holed up at 2am in a spartan, tiny, cockroach-infested studio in Amiens, it was like a familiar voice from another time, cutting through the loneliness in a language I could understand. It wasn’t long after that, that I bought the CD from FNAC record shop. It seemed impossible, but fortunately for me Spoonfed Hybrid were big in France. I listened on repeat, dissecting the words and the colourful clashes of tones. As with every important album I’ve loved since, it led me onto other things and shifted my perception of ‘electronic’ music in particular.

Listening again today, it’s striking how it still sounds innovative, exciting and enigmatic. Over time, its reverie has become steeped in sepia, (the ancient treatment for depression, as well as the stain of faded photographs) and perhaps a little worn and fragile, but no less magical.

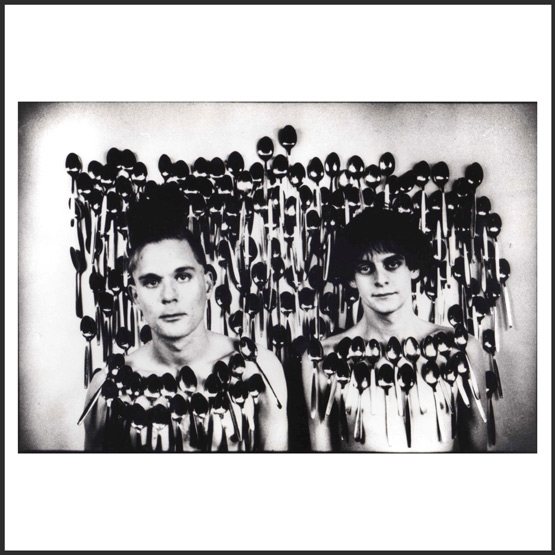

Fast forward 25 years, Spoonfed Hybrid, aka Chris Trout and Ian Masters reflect on the making of the album, the early days of digital recording and take us through this wonderful record, track by track.

For Masters, leaving Pale Saints hadn’t been that big a decision. “It hadn’t been creatively rewarding for a while, and I couldn’t see it about to get any better, so I struggled through the making of the second album, In Ribbons, mainly enjoying it, but I knew it was time to leave”. With no idea what to do next, in the months that followed Ian eventually teamed up with AC Temple‘s Chris Trout. The pair had originally met while Masters was still in Pale Saints. “I had interviewed Ian and Meriel for Ablaze! fanzine and given him a tape of my album ‘Belinda Backwards’ in an effort to impress him, because I loved their first album.”

What was to become Spoonfed Hybrid incubated, slowly, fed by beer and pub conversations about music, until, Masters says “it was apparent that we had both enough in common musically, and also enough not in common musically, to have a go at making some songs together”. But this collaboration would also be a step change in how Ian approached writing music. “I don’t think I knew anything about sampling or MIDI before I met Chris,” he recalls, “on my first visit to Neptune studio in Sheffield, which had, amongst a load of other gear, an Atari PC with a pirated version of Cubase, I saw what was possible with MIDI and samplers and was hooked.” Being the early 1990’s this was a simpler, more tactile era of digital music creation, when plastic stacks of floppy discs held all your important MIDI arrangements, ready to be inserted into computers which boasted 512K of memory. “I bought an Atari 520ST soon after” he adds, “and a cheap MIDI keyboard, and started to mess about. I even managed to sync my Fostex X15 4 track recorder to the Atari, so I could have real instruments and stuff coming off the keyboard simultaneously. Play a part into the Atari via MIDI and then make as many other tracks as you wanted, until either the song was finished, or your equipment was so overloaded that it all froze up”. And, freeze up it did, many times, according to Trout: “I’m not sure whether it was a shortcoming of the [cheap] computers or the fact that the software was a ‘crack’, but I am sure there must have been bedroom dance producers all over the country cursing just as we did when the thing froze up at an important moment and you had to reboot the computer and pick up where you left off.”

The shift in dynamic from songwriting in Pale Saints with four or five members, to writing as a duo, was liberating for Masters. “Chris and I argued a lot, but it never interfered with what was best for the music”. The ideas flowed through not having to write for a band, just writing for their own entertainment with no preconceived ideas about what it all should sound like. It wasn’t about doing gigs either, at least to begin with. Eventually, even to Masters’s surprise, Spoonfed Hybrid were to manage one tour. They enlisted friends and very able musicians to help with the performance complexities of some of the tracks, but for various reasons, the tour was not very successful.

In a process that would today be labelled ‘DIY’, most of the songs on Spoonfed Hybrid were programmed at home on the beloved Yamaha PSS-795 keyboard, which would have set you back all of £100 in 1992. As Trout puts it, plainly, it was “the kind of keyboard you can buy from toy outlets and home shopping catalogues.” The album’s tracks were written and recorded initially in Ian’s bedroom at 33 Harold Avenue, Leeds 6, then developed, shaped and reconfigured over many hours in Duncan Wheat’s central Sheffield studio, Neptune. Wheat, who sadly passed away in 2012, became very much a third member of Spoonfed Hybrid in the process, and was the only choice when it came to finishing up the album at Palladium, the residential 24-track in a big detached house just outside Loanhead, Edinburgh. Responsible for pretty much all of 4AD’s best albums of the late ’80s and ’90s, Palladium was run by Jon and Ann Turner. Trout remembers Jon as “an affable fellow, and mates with Fish out of Marillion, so we lived under the ever-present threat of the great man dropping by for a chinwag.”

However, Spoonfed Hybrid was never released on 4AD but its (arguably cooler, for collectors) off-shoot Guernica, the home of one-off projects by bands not otherwise signed to 4AD, like Bettie Serveert, Underground Lovers and Insides. Twenty-five years on, it seems remarkable now that the album wasn’t part of 4AD’s solid catalogue of that period. Soon after the tour, Masters moved further north, effectively putting an end to Spoonfed Hybrid, although they had a couple more releases; one on a French label called Le Tatou Colérique, and another in the USA on Farrago, sold mostly to us dedicated fans who had fallen hopelessly, headfirst into the first album.

Spoonfed Hybrid, 1993 (Guernica) a Track by Track guide

words by Ian Masters and Chris Trout

1. Heaven’s Knot

Christ Trout: ‘Heaven’s Knot’ was the result of music being made out of the same stuff as maths.

Ian Masters: It was one of the first tracks we started messing around with at Neptune Studio in Sheffield with Duncan Wheat. One guitar chord, panned hard left and right, playing a strange counterpoint pattern.

CT: We’d taken a single staccato distorted guitar chord – not even a chord, two notes together, a fifth – and looped it so it repeated rapidly. I’d wanted to be the Pet Shop Boys for several years, and this was yet another failed attempt. Playing around with the sampler, it transpired that if you played a certain lower looped note along with the original one (its repetition of the original sample slower because it was lower) you got the cross-rhythm of three playing against four that is the basis of the track. The rhythms went out of time if you wanted to play any other note along with the original one, but we could fix that later. The chord sequences are all over the place, I’ve no idea how Ian managed to turn it into something that sounds like a bit like a song by adding the vocal. About two-thirds of the pieces on this album were very much Ian’s babies, with my bits added later, but this one was assembled collaboratively.

IM: For some reason, it always makes me think of Xmas. We were convinced that if 4AD put this out as a single, it would be a hit. They, of course, were having none of it.

CT: Before we decided to ask our friend Duncan Wheat to produce the record – he’d recorded the demos, knew how to work the machines, and was really as essential a Spoonfed Hybrid ingredient as anybody – we’d briefly considered asking Rob Gordon, a Sheffield-based dance producer attached to FON Studio. We couldn’t use Rob in the end, but I’d have liked to have heard what he would have done with Heaven’s Knot. What we did would not sound good in a club, I think it’s safe to say. It would, in fact, sound like a very large bluebottle, although probably still better than the misguided dance remix of the track (‘Token She-Van’) that we released later.

- Naturally Occuring Anchors

CT: For Naturally Occurring Anchors, which in its initial form was mostly just one guitar part and the vocal.

IM: …The harsh guitar editing on the song was decided upon at finding that the mixing desk in Palladium studio could be programmed.

CT: We recorded maybe six or seven guitars playing the same part, but with radically different sounds, and then used the studio’s automated mixing desk (all the rage in 1993, these things) to cut increasingly quickly between the different sounds as the song progressed, giving the whole a Cubist quality it hadn’t previously possessed. The automated lights on the desk blinking on and off were very pretty, so we turned all the studio lights off to watch them when we ran the finished mix to tape. One of the guitar sounds involved hitting the strings with a drumstick with one hand while fretting the chords with the other, which was far too complicated for either Ian or I to pull off alone, so we ended up with him lying on his back on the floor with the guitar while I knelt above him with the drumstick. Jon passed the window with his beard and his lawnmower while we were doing this, and gave us ‘a Look’.

IM: The title comes from a book on Neurolinguistic Programming I was reading. I thought: “I’ll have that”.

- Tiny Planes

CT: There’s a certain set of mildly eccentric guitar chord inversions, two or three-finger jobbies played mostly between the fifth and tenth frets with lots of open strings, that I think of as my own, largely because I’ve used at least some of them in more or less everything ever. Tiny Planes was an exercise in transposing those inversions to the keyboard and making a song out of the result.

IM: We kept some of the Yamaha PSS sounds, but replaced a lot of the others with the ones from a Kurzweil module available in the studio, which were of far superior quality

CT: (basically the same thing for fifteen times the price). There were a fair few where we liked the sound from the Yamaha better,

IM: …mainly the ones with quirky character.

CT: It’s funny, even I think of Spoonfed Hybrid as an “electronic” album in a way. It was made using a sequencer on a computer, but it isn’t really one at all. The keyboard sounds are, almost without exception, imitations of acoustic instruments. In fact, apart from the bass that lasts for all of 30 seconds in the first verse of Heaven’s Knot, I don’t think there’s a single synth sound on the record and we only used the fake electronic oboes etc because we couldn’t play those instruments and had neither the budget nor the charm to acquire people who could.

- Stolen Clothes

IM: Finding the chords on this song almost did my head in. I could hear them, but didn’t know how to play them at first.

CT: It originally had just one acoustic guitar, but at Palladium Studios we set up to record the four of Ian, Duncan, the house engineer Iain McKinna and me playing in the control room at once, and recorded the sound of the room as well as the close mics on each guitar. I’m not sure whether the room sound made much difference to the resultant composite guitar sound, but it was a nice campfire moment.

IM: The tabla, played by Duncan Wheat, really lifts the song. Duncan was almost a member of the band, and it transpired that some of his suggestions came from the synaesthesia he experienced, seeing sounds as colours: “This song needs more red.” There also appears to be just one piano note on the song. How could that have happened if you had a keyboard player in the band?

- Lynched

IM: The vocal level on this seems so low now, especially at the beginning. I don’t remember that much about making this. It seemed to me that it could be used in a David Lynch movie, so I named it that. The percussion is a sample of a spoon being dropped into water, slowed down, first take!

CT: As far as I recall, almost all of what you hear on the finished version of Lynched apart from the vocal was in the bag before we went to Loanhead. I remember listening to it through the open French windows of the control room from my deck chair, thinking, hmm, that could do with just a wee touch of bamboo flute, and going inside to announce my vital creative insight. They humoured me. The bamboo flute was permitted. No, of course it wasn’t a real one. I like the short-wave radio on this song. The sounds remind me of crickets and tropical birds.

- 1936

CT: 1936 was the first piece of music Ian and I made together. We obviously liked it enough to have another go.

IM: The string arrangement was done on the PSS at home, as we couldn’t afford the London Symphony Orchestra, and wouldn’t have been able to write the sheet music for them if we could. The song opens with a ticking noise from the PSS keyboard, which we decided to keep.

CT: The whole thing is built around the same riff, in the sense that the notes the sequencer is playing don’t change, they’re just moved from the rattly sound at the start to the drums and then the orchestra stabs.

IM: What was this song about? No idea, not even after consulting the lyric booklet that came with the Japanese CD version. Who cares? Move on.

- Getting Not To Know

IM: “Too much thinking leaves very little time for living.” Yes indeed. I love the guitar solo Chris did on this. I’ve always thought that 90% of guitar solos were totally unnecessary, and don’t add anything to the song, but this one made the tension higher and higher until the release at the end of the song. The engineer, Iain McKinna, played the nice flamenco-ey guitar at the end because no-one else could.

CT: Neither Ian nor I would have had a prayer. I’ll have sat there going, can you do it more like Roddy Frame?

IM: Ostensibly, the lyrics to the song are about my old band mates.

CT: I always thought they were about his family!

IM: Spoonfed Hybrid live member Ross Orton, who went on to do production work with Tricky, Arctic Monkeys, played drums (well, Octapads) on this.

CT: Because it’s essentially a Rock Band Song, it suffered the most from the weedy production. I like the Escher effect of the descending strings at the end: it sounds like the note is going down and down and down, but really it’s just the same thing three times.

The little interlude prior to Somehow Some Other Life was played by Ian on a metal chair (IM: or was it a radiator?) with four thinnish vertical struts for its back. If you held the chair hard against the floor and plucked the struts, it sounded a bit like a double bass. I dabbed a plectrum at the strings of a fucked autoharp.

- Somehow Some Other Life

IM: One of the features of MIDI programming is that it’s very easy to get hypnotized by looping bars of music, so that’s probably why this song has that kind of repeating pattern all the way through.

CT: For the song proper, I was required to provide a mini E-Bow concerto for the middle section and a wall of howling feedback for the end. So, by way of preparation, I asked Jon to drive me to the foot of the nearest of the chain of small mountains (the Pentland Hills) that you could see from the studio, and indeed from anywhere in Edinburgh that faces south. My intention was to climb the first one and decide from there how hospitable the ridge looked. I imagined myself as a kind of post-rock Julie Andrews, gathering slithery snakes and comely curlicues of pure mountain feedback into my basket to take home for the family. I did get to the top of the first one, there was an easy path from the visitor centre thing at the bottom, but, June or no, the wind was hammering in direct from the North Pole, so I didn’t give the ridge much thought. I just sat down, rolled a fag, smoked the fag, went home.

- Pocket Full Of Dust

CT: I never knew until I read Martin Aston’s Facing The Other Way a couple of years ago that Ivo had refused to release Spoonfed Hybrid on 4AD proper because he didn’t like my singing on A Pocketful Of Dust. I don’t like it much either, to be honest, it was much better on the demo. So it goes.

IM: Ivo said he didn’t like Chris’ voice, but I don’t think there was ever a “Lose Chris’s voice and I’ll release it on 4AD” conversation. It was a team effort. The piano part was written on the piano at my Mum & Dad’s which has, over the years taken some punishment from my clumsy hands. As a consequence of the words being written by Trouty, this has as many words as most of the other songs put together. I never asked him what the words were about, but was surprised when he managed to write such impressive lyrics to it.

CT: The passing cars on the intro were recorded by our own fair hand, taking a microphone with a long lead out the front of the studio. It was dark, and it was June, and it was lowland Scotland, so it must have been reasonably late. And it wasn’t what you’d call a busy road at the best of times. I think we managed to capture two or three, faintly. The studio would have had more BBC Sound Effects CDs than you could shake a stick at. But you’ve got to do all the fun rock’n’roll stuff when you have the chance. Less disciplined artists would have thrown the Sega Megadrive through the French window and pissed on the cat. I’ve heard that Dead Can Dance used to do that all the time…

- Ecnalubma

IM: A coda to ‘Heaven’s Knot’ with bagpipes. Chris played the bagpipes wearing only a kilt.

CT: They weren’t actually bagpipes. I think the sound was supposed to be an accordion. There was a games room upstairs where we had a second computer running Cubase through the faithful Yamaha, and it was there that I made Ecnalubma out of the ghost of Heaven’s Knot and some lovely fake Yamaha bagpipes.

IM: And the title is of course, ‘Ambulance’ backwards, but you already knew that, didn’t you…?

- Boys In Zinc

IM: Probably my favourite track on the album. Starting from a fairly random series of repeating notes, it really seemed to bloom in the studio. I stole the title from maybe a poem about soldiers coming back from war and the lyrics came from there.

CT: I received Ian’s parts on a floppy disc in a padded envelope, with no other information. It’s the only one we did in this manner. I searched in vain for some kind of recurring pattern in the glockenspiel part that forms the backbone of the song, some basis upon which to construct an understanding of the thing’s shape and purpose. Zilch. And of course there were no mobile telephones in those days, so a quick “what the fuck’s going on here then?” text exchange was out of the question. So I wrote the string parts in a seat-of-the-pants style. Does it sound good? Keep it, then. You don’t need to know what the chords are unless your job is to play the chords. If I’d known what the chords were supposed to when I wrote the strings for this, the result wouldn’t have been nearly as harmonically interesting.

IM: Ashley Horner (of the Edsel Auctioneer) made a nonsense video to this one with a lot of walking around on a beach, probably in Newcastle (?), which may be on YouTube still.

CT: It was mainly Druridge Bay and Blyth in Northumberland, with some bits in a studio at Newcastle University. Ashley’s girlfriend Jane was studying marine biology, and took us to the fish quay in North Shields at some ridiculous time of the morning. She seemed to know and have a mutual respect with all the people who worked there. The talk was of the decreasing size and failing numbers of the catch. We didn’t get any footage we could use there.