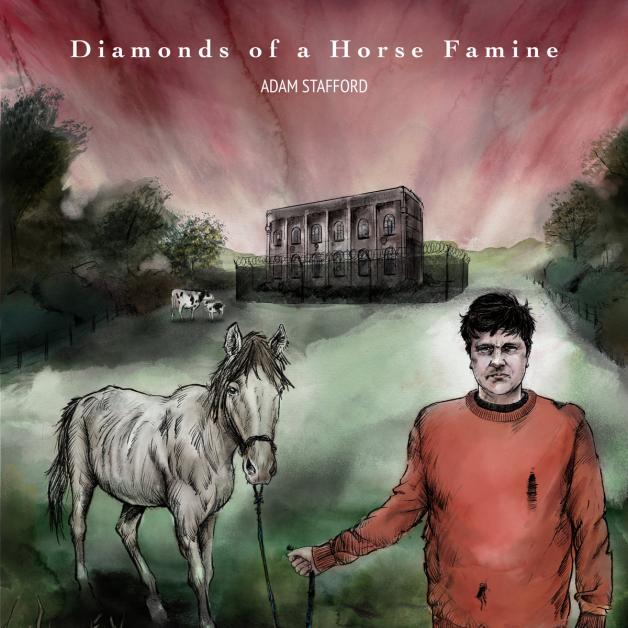

There’s no shortage of negatives about 2020, but let’s focus, for a moment on some of the positives. It’s been a time to work on other projects, some of which may have fallen by the wayside or been forgotten about, or to look at something completely new. In the case of Adam Stafford, it’s been both. His experience of lockdown has proved to be one of renewal, revolving around the discovery of a little red book hidden beneath some tupperware in a cardboard box.

This little red book turned out to be a snapshot of a past life, full as it was of old lyrics and memories. providing the possibility for reassessment, which was wholly embraced by Stafford. Armed with a box of cassette tapes, packed with hundreds of demos, he spent his time re-learning some of the songs, taking fragmented ideas from the past ten years and chop, re-write and re-sculpt until an entirely new album was born. Whilst the mind might boggle at what was included in the book and not shared with the world, some of it stretches back a very long way indeed. Although it had never recorded, the title track was written when Stafford was only 19 and is technically the oldest song on this collection.

He has likened the process to a detective looking over an old case. He also decided to start singing again, mindful that some of his audience had complained he’d stopped. The record was written, performed, recorded and mixed by Stafford at home in Falkirk during May and June of this year. The album opens with the cinematic ‘Thirty Years Of Bad Road.’ It’s beautifully constructed, as is much of the album, even as it deals with themes of addiction and inertia. Balancing dark and shade, both lyrically and musically, it sets the tone for the rest of the album.

Whilst a comparatively short album at 34 minutes, the benefit of that is that, by and large’History Of The Longest Days‘ whilst a decent tune suffers from a slightly self-indulgent wooziness that actually obscures the song underneath, rather as if the tape had got chewed up in the middle of it. While this was probably the intended effect, it’s a shame as it detracts from the song itself.

Yet there’s a lot on display here. It’s a lo-fi sounding record which embellishes rather than distracting from the overall sound, for the most part. It connects with that magnificent Scottish melancholia that infects so much of the excellent recorded Scottish sound from Mogwai to Boards Of Canada, even if the album may be closer to the likes of Nick Drake and Elliott Smith, though the comparisons to Ry Cooder‘s soundtrack to Wim Wenders‘ Paris, Texas are perhaps closest.

So does this detective find himself? Yes he does, and as the last bars of the closing ‘Summer On Elm Wood‘ fade away the book is left open for the possibility of further adventures, or the tantalising threat of what might have been…