I read an advert recently with the words “Musicians have been silenced for 12 months. We *will* enjoy their music together again” in the headline. It stopped me dead in my tracks. With the pandemic, the loss of live events, the dearth of suitable online experiences and the difficulty in making them work, it’s been a challenging year.

I can not imagine how difficult it must be for the artists. I can’t imagine how difficult it is to be unable to do what makes you, you, through no fault of your own, to be unable to do the thing that gives you life, that brings in some kind of income.

But that’s not what made me stop when I saw that advert. What made me stop was the thought that I may never be able to enjoy music or a gig again, not properly, not in the way I want to, not easily at any rate. And that leads me to a story that started many moons ago.

I discovered I had a Cholesteatomas when I was 11.

It shouldn’t come as a surprise in a world of laden schoolbags, BMX bikes and playground squabbles I had never heard of a Cholesteatoma before.

My memory of being 11 was of months of pain, discomfort, and every medical specialist my unrelenting GP could foist me upon; brain specialists, bone specialists, dentists, opticians, more dentists, the ear bloke, the second ear bloke. There were many doctors and many specialists.

I saw them all but my GP was convinced the issue was my ear even though the ear Doctors said it wasn’t. He eventually got me to the specialists specialist. I was in a ward having my head shaved and awaiting surgery within an hour of my first appointment and he barely told us what was going on.

It was a little alarming.

A cholesteatoma is an abnormal growth of cells that forms in and around your eardrum or deep inside the ear itself. I am frequently told how rare they are, but at this stage, after at least three of them, I remain unconvinced. Medical publications will tell you that if a Cholesteatoma is left untreated it can damage the “delicate structures inside your ear”, structures that are essential for hearing, balance and a host of other functions.

What they don’t say particularly clearly is that they can eat through bone, end up inside your skull or go the other way and crack open your brain cavity, causing much worse damage than hearing loss. If death is considered more damaging than hearing loss. Obviously.

They have a taste for nerves, both those that allow you to taste food and those that allow you to smile at weary strangers. Often, if the Cholesteatoma doesn’t get to your nerves first, the ringing, tinnitus, pressure and popping and general botheration of it all will have a good run at them, and that’s only if the surgeon doesn’t get there before any of that.

Those nerves often get in the way of scalpels.

The list of possible outcomes of a cholesteatoma includes many layers of nerve loss, hearing loss, facial paralysis and a lovely thing called CSF leakage, which is when your brain fluid makes its way into the world via the previously mentioned crack in the brain cavity.

This ‘CSF leakage’ isn’t the thing that can kill you. What has a very good chance of killing you is what makes its way back into the brain cavity via that same gap in your skull.

I was 11 when the first Cholesteatoma was found growing slowly in my ear. It would appear that after much toing and froing recently, that first, or possibly second Cholesteatoma made a move into my skull. That hitherto unknown development has led to months of tests and a terminal bone cancer scare. That’s a scary thing, when at an appointment for an ear problem you suddenly realise there are more medical staff than normal and the consultant uses the term multiple myeloma more than once.

I imagine the scream from inside my car traveller further than nature and mechanics intended.

There have been many scans and appointments to figure out what the shadows in my skull CT scan are, that and the sizable air pocket in one of the skull bones demand answers. If my surgeon knew any of this skull base business at the time of the first surgery he failed to mention it in any great detail in my medical records. That was par for the course in ye olden days.

I say I remember pain, but I probably had discomfort and noise, mind-bending, insanity creating, dark pit of despair circling, never-ending, out of tune, out of focus, unstoppable noise. The pain may be a figment of my imagination. I say that as I am currently recovering from yet another Cholesteatoma surgery I had a few weeks ago, and there was very little pain before that.

They say getting a Cholesteatoma is rare, getting two is “exceptionally rare” and racking up three or possibly four across both ears is near unheard of. I can’t tell you how lucky I feel. Where this brings us all is to hearing loss and living in a hearing world with very little of it to go around. I lost all the hearing on my right-hand side when the first Cholesteatoma was removed, and for about the last six months I have been almost entirely deaf on my left-hand side too.

Reader, I can tell you it isn’t and has not been pretty.

The past six months have been terrifying, eye-opening and inspirational in equal measure. You learn a lot about yourself when you lose something as fundamental as your hearing. You learn a lot about other people, their patience levels and their empathy, you learn to shield yourself from the impatient, the self obsessed and the hurried, you learn about who you can rely on very quickly and you learn to slow down.

You learn to slow down.

You learn that being near deaf in the middle of a pandemic with a never-ending whistle inside your head when everyone is wearing facemasks is an absolute pain in the arse. You learn that you can’t trust yourself to drive, or go out on a bike. Phone conversations are a thing of the past, headphones, even really loud ones, are a no-no, a translator is required for even menial tasks and it takes a very brave cold caller to ring your number or knock the door.

But it’s the music that kills me.

I’ve been going to and or working at gigs in one shape or another since I was volunteered to help the “stuff picker-upper” at a Watercress gig in The Empire in 1995.

As I write I’m currently running on about 15% of the hearing I should have, probably less, I haven’t had an unimpeded telephone conversation since before Christmas but I have been spared Zoom calls on account of the ears not dealing well with dodgy connections and feedback.

The soundbar for the TV has not been lower than 100% and subtitles can often get in the way of the picture. When they exist. They often don’t, even on new-fangled devices and streaming films. Imagine that. Scripts exist but we just can’t be arsed adding them onto the content on screen. I’m looking at you Amazon and Sky TV. It has been a long six months.

A very long, quiet six months.

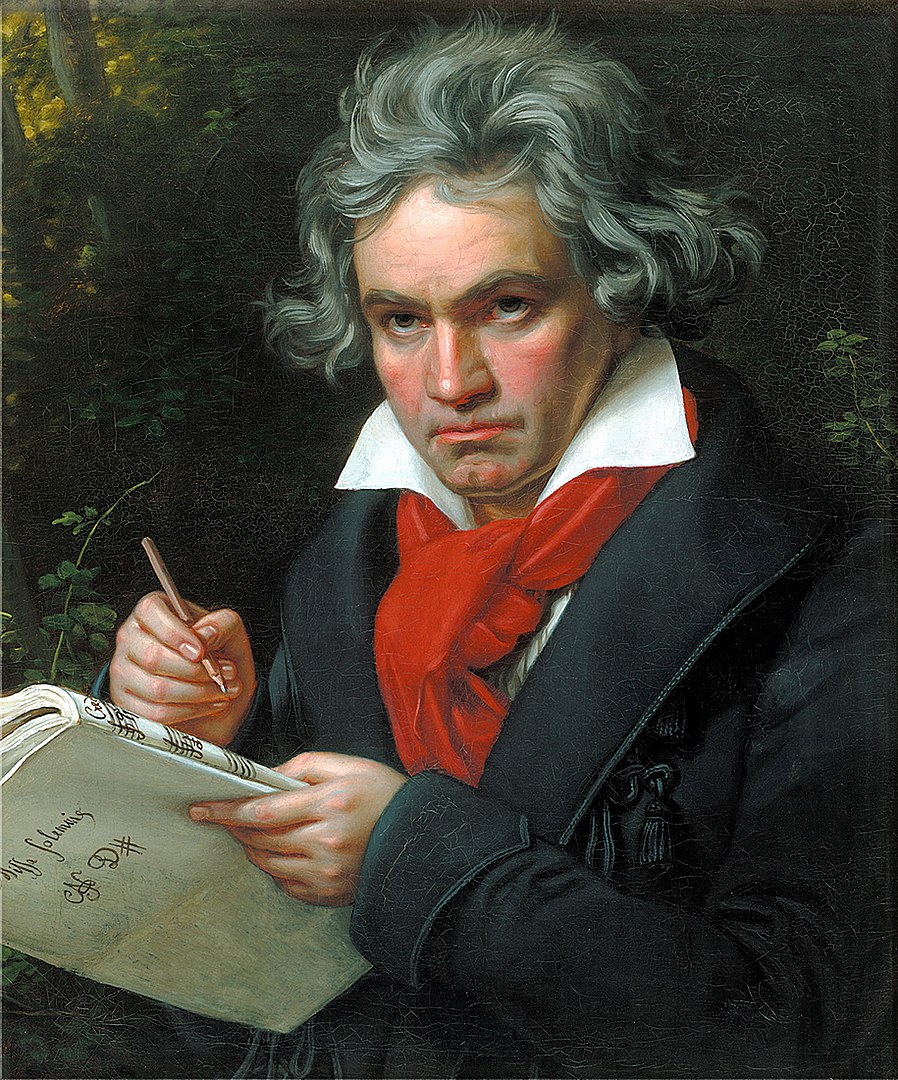

I was quite happy living on par with fellow deaf on one side folks like Stephen Colbert, Bruce Willis, David Hockney and, well, Beethoven. You learn to cope, to sit at points in a restaurant or a meeting where you’ll hear, walk on the right-hand side of everyone, get tech that allows you to switch everything to mono, that kind of thing, there are tricks, things you can do. It’s passable. Manageable. For the most part. For the most part, you put up and get by.

But near-total loss immediately isolating, scary, it feels like some other world where echo and distortion are paramount, where every sound feels like it’s coming through the outsize tank at Sea World, all muffled, dull, dead. Lost someplace.

I was at a gig a while ago on Penny Lane in Liverpool, to say it was a struggle is an understatement, the music was lost on me, the chatter among larger groups impossible and my ability to write a review to go along with my photographs a thing too difficult to rectify.

The point when the room went very quiet in awe of the artists on stage and I could hear none of the noises creating the awe brought forth a tear or two. It’s a heartbreaking thing when you discover the thing you love is just, just out of reach.

I think that’s where the problem is.

For me, for others I know, loss of hearing over the long term is manageable, this sudden loss feels like theft. Nothing matches your expectations, nothing matches your memory, distortion overrides reality, the muffled noise becomes the new you, the new soundtrack, the new reality.

It is a strange, frustrating world that moves at a spectacular rate while you try and read the garbled subtitles juddering across the screen.

The film Sound of Metal came up in an online chat not long ago, I was told by many friends to avoid it as it was probably too close to home. I was told by a few that the main character, Ruben, played by Riz Ahmed, was annoying, selfish even and that he was never going to be happy with an ‘attitude like that’. And that is the bit you’ll probably never understand.

That frustration, that anger, that sadness when you realise what has been stolen, that heartbreak at the knowledge that the thing you love will never sound the same again, the confusion over what you hear and what your brain tells you it should sound like is indescribable.

Insufferable.

So many of our memories are made up of sounds; moments in music; that first teenage crush, the first record, the first dance in a club, the first gig, the first song to track a breakup, the first dance at your wedding, a song played at a funeral, your favourite gigs, your worst gigs, Sunday night sessions, festivals on a Friday night, everything has a soundtrack.

Every day has a sound, if it isn’t the one you put in it’s there in the space around you, in nature, in the plumbing and on the high street.

What do you do when someone hits the mute button, when your life becomes one long zoom call where everyone is waving their arms about and you can’t unpress the button, what then?

Without wanting to sound like a cheap print off Wayfair or Wish, I am blessed that the deft hands of a surgeon seem to have saved most of the hearing on the left-hand side. We’re not there yet but the volume is increasing, the world is becoming louder again, it’s almost a little alarming how loud some things are. If the Cholesteatoma is gone then we win, for now; this is a battle, not the war, whatever sound we get now is a reprieve.

A temporary win.

For me to tell you to look after your hearing seems trite, it feels more important to tell you to enjoy every bum note, every cheeky joke, every podcast, album, interview and every single thing you can get into your ears.

More than that though, you should look out for them, get good earplugs, avoid the moshpits and the really big speakers and take your time with people who live in a world much quieter than yours. If you ever end up working in TV sort out the fucking subtitles.

More importantly, after months of silence, enjoy the show, get to as many gigs as you can, buy music direct from the artists and sing like no one’s listening.

Beethoven image by Joseph Karl Stieler – https://web.archive.org/web/20160623080009/http://www.archiv.fraunhofer.de/archiv/presseinfos/pflege.zv.fhg.de/german/press/pi/pi2002/08/md_fo6a.html, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=165990