Welcome friends to part three of my Rolling Stones potted odyssey; celebrating the bands 50th anniversary of mixed fortunes. This third episode in the series begins with Jean-Luc Goddard’s Sympathy For The Devil documentary and covers the death of “little boy blue” Brian Jones, Stones In The Park, Altamont and a survey of their most memorable and notable releases.

21. Rock & Roll grows up as Jean-Luc Goddard adds gravitas.

The existentialist poster boy and revered founder of the “La Nouvelle Vague “ style of film-making, Jean-Luc Goddard’s faux-documentary/political tableau on the Rolling Stones most accomplished (arguable I know) opus, Sympathy For The Devil, is an often uncomfortable ride. Adding a gravitas, almost unparalleled in the Rock & Roll world, to the Stones rhetoric, Goddard’s semiotic and various themed set pieces traverse Maoism, Marxism and Black power through a series of labored narratives and readings. Memorable shots include the surrealist Scrapyard sequence in which black militants arm themselves to the sound of revolutionary texts, as a gaggle of white women are dragged to their impending execution. There’s a myriad of these controversial scenes, including the most unusual bookshop ever (customers flicker through pulp fiction, super hero comics and top shelf material; mingling with Maoist rebels and their hostages, and fascist saluting kids), which mope and gravitate around the Stones Sympathy For The Devil rehearsals.

Just like The Beatles, Get Back, the previously entitled One Plus One fly-on-the-wall film shows all the hidden tensions and implosions steadily building within the group – the ghostly, fading Brian Jones almost redundant, relegated to a sulking walk-on part. As a captured moment in time (theatrical release, 30 November 1968) Goddard perfectly captures the philosophical and experimental spirit of the music scene; as the Stones progressed from the raw primitive, howling teenage love paeans of I Wanna Be Your Man, to the existential angst and fears of Beggars Banquet within just five-years.

22. Brian Jones Takes The Final Dip Of No Return

Cast adrift from his band mates in a miasma of jealousy, conceit and lackluster, Jones’ capacity for self-destruction was becoming a real drag. The rot had already set-in before Beggars Banquet, and continued unabated with further drug busts and raucous behavior, addling Jones until he was all but useless to the Stones. In June of 1969, with an impending US tour on the horizon, Jagger, Richards and Watts paid a visit to Jones East Sussex home, Cotchford Farm (once home to the author of Winnie The Pooh, A.A Milne) to discuss his future: A future without the Stones. The dandy coifed blues scion had sunk into the alchemist cabinet a little too often, fully aware that he was in no state to get back on the road. As it turned out, the Yanks refused him a visa anyway.

Bloated and now bereft of his musical comrades – the revered British blues pioneer, Alexis Korner is adamant that Jones was in an upbeat mood, preparing to form a new group with him – Jones sunk into the mire, literally. July 3rd 1969, Jones body was found lying motionless at the bottom of his swimming pool. He was 27.

No one will ever know the whole truth of the events of that night, though many have tried to concoct and suggest countless conspiracies, from tomfoolery turned tragedy to motorcycle gang revenge. Jones friend and the man responsible for overseeing the building work that was taking place on the former Stones country abode, Frank Thorogood remains the most likely candidate – the last person to see him alive after joining Jones and his houseguest Janet Lawson for drinks; a supposed and unconfirmed confession on his deathbed is held-up as further evidence of his guilt. Arguments over delay’s in receiving money counter-charged by Jones’ suspicions that items from his home were being stolen and that the builders were taking the piss, may have fueled the speculations that Thorogood finally lost his rag and did the contrary rock star in. Though the case was reopened, only a few years ago, no charges have ever been brought, the original corners verdict of “misadventure” remaining stoic – a pertinent condemnation and summary of Brian Jones life in some ways.

23. Honky Tonk Women / You Can’t Always Get What You Want

An A and B side that any group would gnaw their right arm off for, Honky Tonk Women and You Can’t Always Get What You Want was the perspicacious interregnum between Beggars and Let It Bleed.

‘Tripping the light fandigo’ on a ranch located in the Matao surroundings of Sao Paulo during their Christmas/New Year break, Jagger and Richards sucked-in the humid, arid Brazilian air for inspiration. Intrigued by the local gauchos, the ‘Glimmer Twins’ began work on a slinky, boozed-up country song entitled Country Honk.

Between that holiday and the sessions for Let It Bleed, this Hank Williams imbued number became the prowling Rock & Roll anthem to the ‘gin-joints’ and pick-up bars of Memphis, Honky Tonk Women: The Honky Tonk reference both a raw bawdry musical style and appellation for the prostitutes who traded their wares in these establishments. Two versions were recorded, the original hoedown making the LP, whilst the electric became the single.

Recorded around the same time as Beggars Banquet, this jangly refrained Stones calling card seemed an ideal candidate for that album. Delayed till the following year, You Can’t Always Get What You Want, became the flip side track of the Honky Tonk Women single and was the finale curtain raiser on the Stones final album of the 60s, Let It Bleed. Commentators and critics are only partially correct when they suggest that this is a lamented swan song to the end of a decade, as there’s also a clear allusion within the melody and lyrics towards an uplifting optimism. Add to this the choral reverence of the London Bach Choir, whose angelic exhalations are both innocent and pretentious – Richards own ambitions in the Dartford School choir were cruelly taken away when he his voice broke at thirteen; a moment that he still harks back to and sadly laments, as testified in his recent biography.

Amusingly those prissy choristers got cold-feet when the single was released; asking for it to be withdrawn after it dawned on them that the Stones were not as pure-as-the-driven-snow. Good sense prevailed and they withdrew their fatuous outrage.

24. Stones In The Park

Brian Jones premature and out-of-the-blue death just days earlier didn’t stop the Stones from fulfilling their commitments to Blackhill Enterprises, whose free concert in London’s Hyde Park was set to attract an audience of 250,000. Headlined by the Stones and featuring King Crimson, The Third Ear Band and Family (amongst many other head bands), the counterculture concert was turned into a memorial to Jones. In true flamboyant regale, the band opened with Jagger reciting from Shelley’s most famous elegy, Adonais: “Peace, peace!/He is not dead/He doth not sleep/He hath awakened from the dream of life.”

Thousands of butterflies were then released and the band stalked onwards into one of Jones favorite songs, Johnny Winters’ I’m Yours And I’m Here.

A mixed performance made more poignant by bereavement, the Stones trialed numbers from their upcoming LP, Let It Bleed, and favorites from the back catalogue; breaking-in, so to speak, their newly acquired band member, Mick Taylor (formally of John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers). Immortalized by Granada Television, the concert was given the rather iconic, Stones In The Park title.

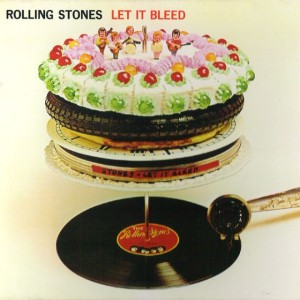

25. Let It Bleed

Knocking The Beatles Abbey Road off the no.1 spot on December 5th, 1969, Let It Bleed continued the good form laid-down by Beggars Banquet. The Stones now sounded like a band that had nailed their style, settling into the worn Rock and Roll, and swaggering country blues, blueprint, which would see them through the next forty years. It will come as no surprise that Brian Jones contributions, before his final night swim, were scant: Autoharp on You Got The Silver, and percussion on Midnight Rambler.

His replacement, Mick Taylor, entered the fray at a late date – most of the Let It Bleed sessions already in the can – though his licks can be heard to great effect on both Country Honk and Live With Me; but contrary to belief, Honky Tonk Women – which Richards swears Taylor helped to change into the electric version – was already in its complete form when he joined. Richards had been forced to incorporate Jones’ guitar parts since 1966 – pushed to the limit on tour as Jones jettisoned the guitar to flirt with the marimba and shakers! -, a dual role that doubled his workload and pissed him off. Taylor than, would be an asset, taking a load off Richards laden shoulders.

Texan sax player Bobby Keys and the great southern drawling journeyman, Leon Russell, made guest appearances as the Stones reliable, silent partner, Nicky Hopkins jingle-jangled away on the ivory.

The sickly oozing decorated cake/record-player cover (baked by an unknown Delia Smith) conceived by artist and ad-man, Robert Brown John, is a surrealist statement that seems ill at odds with the, mostly, conventional music within. Imbued by their roots, Richards bluesy lament to his voracious, cultured firebrand, muse Anita Pallenberg (who he took off Jones, and if it’s to be believed, also had a thing going with Jagger), You Got The Silver, sits well with the bands earthy cover version of Robert Johnson’s, Love In Vain.

That ‘honky-tonk’ scuzz is repeated on the goer, Live With Me, and bad acid-trip paean, Monkey Man – “All my friends are junkies” – whilst the sneering miscreant leery ode to a roaming prowler, Midnight Rambler, features southern-boys style harmonica and watery veiled vocals.

Greil Marcus called it, “the greatest rock and roll recording”, Gimmie Shelter is perhaps the crowning glory of that album…

26. Gimmie Shelter

Opening the Stones Let It Bleed, the maelstrom churning Gimmie Shelter was the heralded backdrop to the tumult times. Envisioned as an apocalyptic soundtrack and inspired by the street fighting protests, Vietnam war, and spirit of revolution, the Richards/Jagger plaintive opus inadvertently became the film makers savior – check any post-Vietnam or social unrest documentary and film to find it adding a poignant buzz, though the recent Eastenders promotional segue way doesn’t count.

Jagger is shadowed by the actress/singer Merry Clayton, her ‘Orleans rich gospel shrieks and soaring wails adding a touch of voodoo soul.

Unfortunately, Gimmie Shelter would also encapsulate the end-of-the-dream, the song title becoming the synonymous moniker for the tragic Altamont disaster; a concert relished by the devil himself.

27. Altamont 666

Almost singly held responsible for chucking a bucket of cold sick and stinking shit all over the 60s dream, the Stones disastrous and tragic free festival at Altamont nearly sank the band’s career for good.

Alongside the rabid malcontent ravings of Charlie Manson and the horrendous murders of his “Family” converts, Altamont is second only to the opening of Pandora’s bloody box and Satan’s resurrection in many reporters, critics and, even, fans eyes.

Whether they were ever asked to play or the band’s egos went into overdrive, the most eventful weekend of the counterculture’s golden age (alongside a year later, the Isle Of Wight Festival), Woodstock, didn’t feature the Stones. In some ways they were out on their own, adrift of their contemporaries; outsiders.

Touring America at the time, with a documentary film crew in tow (a big mistake) the band announced plans to perform at a free event on the last leg of their exhaustive tour.

Things started to go awry when the original site, the San Jose State Practice Field, decided to pull the plug, leaving the Stones promoters to seek out a new venue. Golden Gate Park was next on their list but various guarantees and filming rights issues forced a change at the last minute. Though it seemed like they’d snatched victory from the jaws of defeat, the eventual Speedway site of Altamont in North California would soon become the synonymous by-word for fuck-up.

Devoid of even the basics in facilities and ill-prepared for an influx of 300,000 plus heads, hippies, cranks, dopers and fans, the Altamont site didn’t even offer up a stage for the band to perform from. A ramshackle, boot-high platform was built at the late hour, right at the bottom of a slope; another big mistake – the crowd pushed down like that wave from Hokusai’s colour woodcut, battering the shoreline stage, with the bodies washing-up crushed at the feet of the Stones.

But just to add an oil tanker’s worth of lighter fluid to the tinder box of bad omens, a decision was made to let the local Oakland chapter of Hells Angels take on the role of security.

Rather generously the Stones asked Santana, The Flying Burrito Brothers, Cosby, Stills, Nash & Young, The Grateful Dead (who never even played, shocked by the ensuing violence) and the Jefferson Airplane, to join the party. The untethered, unruly Angels showed just how big a mistake Jagger and company had made when Jefferson’s Marty Balin was punched unconscious by one of the thugs. This was only a warm-up as cars were stolen and a litany of crimes committed, whilst some poor unfortunate drowned in an irrigation channel.

The piece de resistance however was saved for the headliners, whose fraught and trembling set was constantly interrupted by the crushed audience and antagonistic security. The Angels’ ranks included the intimidating Sonny Barger, the archetype outlaw motorcycle gang leader and protagonist of Hunter S. Thompson’s infamous ‘gonzo’ exposé (an episode he was lucky to escape alive from), and his brood of high and rotten drunk, foaming-at-the-mouth, minions; their moody wrath turned on the hippies, who they began beating to mush.

Whether showing-off or so out of it he just wasn’t aware of his actions, the lime-green suited Meredith Hunter chose the most inopportune moment – to his fatal cost – to pull out a gun. Hassled by the so-called ‘security’, Meredith pepped-up on methamphetamine, triggered a brutal shit-storm of violence, as he was set-upon and pulled apart by the knife and cut-off pool cue stabbing Angels; whose cries of self-defense actually saw one of their clan, Alan Passaro, acquitted of all charges, even though a man lay dead.

The shocking moment in which Meredith is murdered was inadvertently captured by the Stones documenters, Albert and David Maysles and later used as evidence in the case; it was also shown to a dejected and remorseful Jagger (his reaction is caught on the documentary) whose face said it all, the shock sinking in gradually as what should have been a strident peacocking performance to back their incumbent title of best rock and roll band in the world, turned into a living Hieronymus Bosch nightmare.

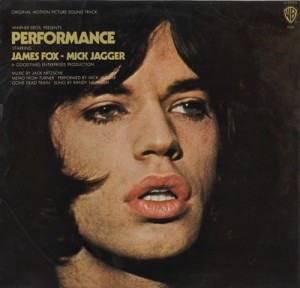

28. Performance

Exaggerating his own pruning, flirty and languorous persona to good effect, Jagger eased into the role of…well, the role of Mick Jagger. Playing an eccentric former rock star named Turner, who dwells with his two concubine lovers in a bohemian London mansion, Jagger didn’t have to dig very deep to find his inspiration.

The drudgery of sex-on-tap and acid is interrupted by the, hinted, ado-masochist gangster-on-the-run Chas (played, rather strangely, by that Eton-attired and well-bred doyen, James Fox). Homoeroticism and psychosis go hand-in-hand with the deep metaphorical questions on identity.

Filmed in 1968, the controversial, halcyon tripping British movie had to wait until the summer of 1970 before it surfaced. Richards nemesis (his autobiography details their falling out) Donald Cammell directed Performance alongside the visionary auteur, Nicolas Roeg, ramping-up the nudity and winding the Stones pirate king up by pairing his then girlfriend, Anita Pallenberg (whom Cammell had also dated once), with Jagger and encouraging them to ‘do it’ for real. Cue a scenario of tit-for-tat sexual liaisons, as Richards paranoia that the two were having it off, led him to sleep with Jagger’s own muse, Marianne Faithfull. Tensions subdued and everything went back to normal, well as normal as can be expected.

29. Brown Sugar

Debuted at the doomed Altamont gig, the pouting, peacock strutting Brown Sugar leapt from those bowels of hell to strike gold for the band in 1971.

Forced to break ties with their manager, Allan Klein, the groups second decade didn’t start well. On top of this their Decca epoch was running out, intensified by contractual problems, small print, and rapacious creative accountancy problems that left the band in chaos, and unable to control their own back catalogue. Further courtroom battles continued throughout the 70s, as Klein worked out a cute move that filled his pockets for years and years.

Cutting free from their obligations the band set-up a new label with the exalted and respected inheritor of the Chess Records legacy, Marshall Chess. Rolling Stones Records first release would be this cuckold salacious classic, a loose tribute it’s believed, to Jagger’s on/off, secret girlfriend, Marsha Hunt (who by all accounts was a sultry Amazonian firecracker).

Brown Sugar is one of those proto Stones swaggers, a real sweaty saucy affair and amongst their most cherished and memorable numbers.

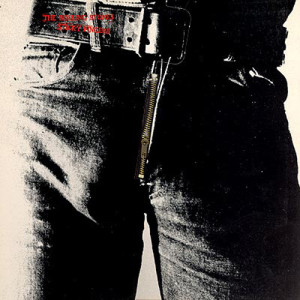

30. Sticky Fingers

Partially inspired by the consanguineous like relationship between Richards and the country-rock pioneer, Gram Parsons, Sticky Fingers eases its self comfortably into an indolent Nashville-tinged musical landscape. The Stones ninth studio album – complete with Warhol’s sleazy innuendo cover – pays its dues to Gram in many ways, beginning with the moving balled, Wild Horses, its title taken from him – the Stones graciously allowed him to record a version for his own Flying Burrito Brothers album, Burrito Deluxe the year before. Another imbued ode, Dead Flowers (“Send me dead flowers to my wedding/And I won’t forget to put roses on your grave”) plays close to the twanging jaunty spirit of Gram era Byrds; a Sweetheart Of The Rodeo lesson in atavistic country blues.

The only good thing to come out of the Stones 69 tour was their impromptu hiring of the, now legendary, Muscle Shoals Studio in Alabama. With new songs to record and feeling hot, the group was desperate to lay down some recordings without any fuss and with the utmost desecration. Down south in the swampy outlands of the “heat-of-the-night” country, the effete, foppish Stones laid-down a number of diaphanous solid, languorous blues and soul numbers; the Muscle Shoals sound and sweltering air of sweat and blood seeped into every note. Set-up by a shit-hot tight rhythm section of local session musicians, the studio would see Artha Franklin, Wilson Pickett, Canned Heat and The Staple Singers, shuffle through its earthy, unpretentious doors. Tracks such as the Otis Redding (arguably a reworking of Redding’s I’ve Been Loving You Too Long’), Stax redolent balled, I Got The Blues, and hung-loose, jamming southern boogie, Can’t You Hear Me Knocking, are just two examples of the Stones inspired short-stay down Alabama way.

Other impressionable numbers included the bottle neck plaintive Sway, which featured a begging and plaintive solo from Mick Taylor; and the poetic peregrination, moonlight Mile. Sticky Fingers would drag a heavy burden of weariness from life on the road and the increasing heavy use of drugs; adhered to on the dirge-y Sister Morphine. A bad trip too far, this craning and swaying muffled lament was originally recorded by Marianne Faithfull (who had to fight to get her rightful writers credit, after she helped to form this burgeoning Jagger/Richards song) and released as a single in 1969. The Stones own version features the same slide guitar cameo from Ry Cooder, though its pretense is a little wish-y washy and pretentious.

Many of you will of course howl disgustingly at this, but after Sticky Fingers the rot set in, with more misses than hits. Even Exile On Main Street is iffy despite the reverence and critical acclaim poured on it. The declining spiral of hedonism, disinterest and lack of ideas left the Stones adrift, unable to deal with the changing mood in music. They would return to where it all began: Rock and Roll. But more of that next time in part four of this potted Rolling Stones tribute.