While the decades preceding influenced the stereotypes of women in the limelight, it was the 1990s that moulded a lot of our current perceptions.

The decade ran amok with iconic women; sometimes characters were strong, often they were fickle, and occasionally they were both at once. From punk in the United States to the laddette culture in Britain it was nigh impossible for female musicians to avoid some sort of pigeonhole. It’s become a poignant and long running problem, not just in terms of sexism, but of discrimination in the entertainment industry as a whole. It’s the idea that artists and professionals need to fulfill a certain label, and become part of a scene to justify their existence. This article will attempt to sort through the humdrum and contingencies, to the female musicians that really represented in the 1990s.

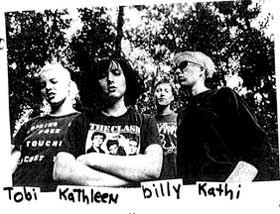

To most indie fans the obvious reference is the Riot Grrrl that enveloped Olympia at the time. Initiated as a reaction to the exclusivity of subcultures in America, Bikini Kill, Sleater-Kinney and Bratmobile symbolised the movement, thanks in no small part to their early 1990s fanzines. Promoted by the then new record label Kill Rock Stars, and already established bands like Sonic Youth and L7, Riot Grrrl quickly grew in notoriety.

Bikini Kill – Rebel Girl by melmtree

Encouraged by the key members’ political and feminist convictions, Riot Grrrl become known as a reaction to the predominantly male orientated grunge scene. Testosterone levels undoubtedly influenced the movement. In an interview at the time, Kathi Wilcox proclaimed:

I’ve been in a state of surprise for several years about this very thing. I don’t know why so-called punk rockers are so threatened by a little shake-up of the truly boring dynamic of the standard show atmosphere. How fresh is the idea of fifty sweaty hardcore boys slamming into each other or jumping on each others’ heads? Granted, it’s kind of cool to be on stage and have action in the front, much more inspiring than to look out at a crowd of zombies, but so often the survival-of-the-fittest principle is in operation in the pit, and what girl wants to go up against a pack of Rollins boys who usually only want to be extra mean to her anyway just to make her “prove” her place in the pit. This was the case when I was first going to shows, and it’s sad that things haven’t changed at all since. And I usually took the attitude of “Fuck them, I don’t care if I DIE in there cuz I can be in front for this band I want to see,” and I was kind of into the violent aspect of it anyway. But it would have been so cool if at one of these shows someone onstage would have said, hey let’s have more girls up in the front, just so I could have had more company and girls over to side could have seen better/been in the action.

So yeah, we do encourage girls to the front, and sometimes when shows have gotten really violent (like when we were in England) we had to ask the boys to move to the side or the back because it was just too fucking scary for us, after several attacks and threats, to face another sea of hostile boy-faces right in the front. Especially when it was at the expense of girls who really wanted to see us and liked us anyway, who stayed in the back. And it’s also for the safety of the boys, because a few times the girls have gotten a little out of control, like when we played with the rocking Tribe 8, if I was a boy I would stay far away from the wild chicks in the pit, FOR REAL. As far as why people are scared, well cool boys and the real punk rockers know that shaking up the scene can be a good thing and aren’t necessarily as reactionary as the poseurs who get all their ideas and fashion tips from Mtv. It’s just like real life.”

However, these women were also a product of their decade. On Kathleen Hanna’s Herstory page, the Bikini Kill and Le Tigre front woman reminisces, “While I loved school it was often frustrating. There were hardly any women’s studies courses at the time, and some of the male photography professors were openly sexist”. Likewise many artists were involved in feminist activism from an early age, having been introduced to the topic by their first wave Mothers. It was no coincidence that the young adult generation of the time rallied against inequality.

At the same time female musicians in Britain were battling not with, but in their own antithesis – Britpop. Women weren’t excluded from the genre, yet although the scene was less aggressive than grunge, twenty years down the line the two acts that continue to be championed as trend setters are the male Blur and Oasis.

That’s not for lack of female talent. Elastica, Sleeper and Garbage offered as much, if not more musically. They also met the benchmark in terms of sales: in 1994, Elastica’s self-titled debut was the time the fastest-selling debut album ever in the UK, and eventually went Gold. Garbage’s 1995 debut entered the national Billboard in the Top 100 and lead single “Stupid Girl” was nominated for a Grammy!

What made the difference was the amount of celebrity coverage awarded to these bands in the press. Blur and Oasis thrived off a well documented opposition; Jarvis Cocker’s actions ensured Pulp were heard, and – as always – high street music publications favoured men, and not women, for their front covers. Alternatively the biggest cache of gossip awarded to female musicians was when Justine Fricshermann’s love triangle with Damon Albarn and Brett Anderson of Suede erupted. Cynics might now dismiss that as the repercussion of her life choices, but ask yourself this – why did the press not present Fricshermann in a more appealing light? It would have been easy to cast her in the wanted, in demand role.

Courtney Love met similar problems to Frischermann when her love life inflicted on her career following her marriage to Kurt Cobain. The struggle for control that ensued has literally gone down in history; the Hole front woman is still persecuted as a “black widow” and accused of being fame hungry. Yet previous to meeting any of Nirvana, Hole had released their stellar and well received debut Pretty on the Inside, and Love had spent time in the soon to be hailed Babes in Toyland. You can revel in horror at dubious paparazzi shots all you like, but the fact is in terms of music – Love made her statement and mark well before her marital car crash.

While the independent industry rampaged with direct and indirect nuances, the mainstream profited immeasurably from the idea of girl power. A term coined by Top of the Pops Magazine to describe Spice Girls, a girl group who in turn were marketed as the alternative to the recently dissolved Take That, ironically from the discernment of the public girl power overcame all the obstacles women on the indie scene still faced.

Of course in reality they were very much an engineered product, and any involvement in it was neither feminist nor sane, but still what Spice Girls did for women in the pop industry was legendary. They paved the way for All Saints, Girls Aloud and The Saturdays, but more importantly they allowed their audience to believe they were in control. In doing so, they introduced the wider public to the idea of female personalities being equal to their male counterparts and competition. That – unnervingly – was one of the biggest achievements of the music industry in the 1990s.

…And because I love her and ending on Spice Girls isn’t exactly credible: