Mark Hollis passed away on this day in 2019. The phrase genius is often overused but Mark Hollis’s music with his group Talk Talk were timeless and towering and worthy of its connotations. Hollis possessed an incredible vocal talent, trembling and soulful, he had an ability to contort each note, infusing it with a shot of vivid emotional clarity, like a life-raft at sea, offering a centrepiece to the disparate sounds that floated around it.

But what was perhaps so constantly illuminating and impressive was the depth of his songwriting ability and his unwavering and uncompromising vision one that would take flight, something which constantly evolved Talk Talk’s sound, a grand ambition matched by a remarkably consistent high level of quality songs. So there’s an argument to be made that Talk Talk are the greatest British band ever.

As Ben Myers wrote in 2011, they were “a rarity in the 80s pop milieu, Talk Talk treated pop, not as a shallow medium through which to get laid/rich/a sports car but, thanks mainly to frontman Mark Hollis, a conduit through which to explore uncharted waters, often in painstakingly detailed production. They went from new romantic synthpop to the avant-garde by way of chart success.”

Born in Tottenham in 1955, Mark Hollis quit his studies of child psychology at Sussex University to pursue music. With the help of his brother Ed Hollis, he formed The Reaction in 1977. The Reaction released only one single, ‘I Can’t Resist’, in 1978. After recording one other track (a rough version of Talk Talk), Mark Hollis ended the band in 1979 to focus on writing his own songs.

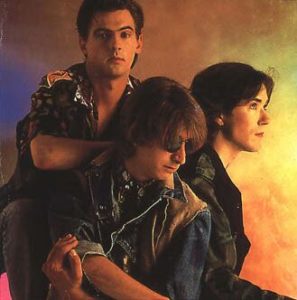

In 1981, Lee Harris(drummer) and Paul Webb(bassist) were introduced to Hollis and Simon Brenner(keyboardist) by his brother Ed and the band Talk Talk was formed. Island Music allowed the group demo time and after they impressed with their sessions and live shows, they were signed by EMI.

Talk Talk released a self-titled debut EP that they later worked into a full-length album. The sweeping synth-pop of their 1982 debut long player ‘The Party’s Over’, much of the record is underscored by a melancholic air, the sound of disappointment and wistful endings, which is ironic for a debut album.

Supporting label mates Duran Duran on tour around this time, the band charted in the UK Top 40 with two of the singles. Talk Talk’ which is brimful of naggingly infectious pulses, Webb’s bounding bass and the shout-along choruses are playfully buoyant: it’s a release of frustration. While ‘Today‘ bristles with a vibrant chorus of sumptuous synth lines, a rich propulsive beat and Hollis plaintive vocal, it has something in common with mid-period Depeche Mode.

The record was produced by Colin Thurston (who had previously worked on records by Duran Duran and Howard Jones) he was chosen by Hollis for his engineering work on David Bowie‘s ‘Heroes‘. Early Talk Talk were surfing the lines of new wave, new romantic and pop they coined a sophisticated form of synth-pop that sounds like it’s influenced by Japan, see the artful refrains, string stings and strident keyboards of ‘Mirror Man’. A very substantial and promising debut with standout moments, The Party’s over scraped the UK album top twenty landing at twenty-one in the chart, but that was just the start of their story.

After its release, the band added unofficial fourth member Tim Friese-Greene, who became Talk Talk’s keyboard player, producer, and Hollis’ writing partner. Although a major contributor to the band’s studio output, Friese-Greene did not usually play with the band during live shows or appear in promotional material.

“The main reason we used him was that he’d done three singles that we knew of at the time which was Tight Fit ‘The Lion Sleeps Tonight’, ‘Cry Boy Cry’ Blue Zoo and Thomas Dolby ‘She Blinded Me With Science’. What was good about him was he’d just produced three records that were in totally different areas of music all very well and he hadn’t imposed a production sound on any of them.” Recalled Hollis of Friese-Greene in an interview with Electronic Soundmaker in 1984, “You get producers like Spector or Steve Lillywhite and you know the producer in a lot of cases before you know who the band is. Also, he was obviously someone who was really good at listening to songs. It was just a matter of gettin’ together with him and seeing if he was a gambler.”

With Friese Greene’s growing influence and a rotating cast of players, each Talk Talk release would become more expansive and progressive reaching ever further into the horizon, and ever deeper into the subconscious worlds. They produced not just great pop singles(although they produced many), but a golden run of meticulously produced seminal records, taking strands of influence from jazz, classical, folk, blues and pop but embellishing everything to simply create music that sounded like, well, Talk Talk, long players as artworks, monuments, built to last.

Life-affirming follow-up ‘Its My Life’ is an audacious record by now Talk Talk had expanded the list of contributors and were moving more in the influence of sophisti-pop era Roxy Music, infusing intensely personal moments into their developing their own sound. Synthesizers and drum machines still underpin each song, but they are now crafting song suites littered with actual “real” instruments and samples, rhythms influenced by the African continent.

The title track alone is one of my favourite Talk Talk songs. It’s one of their great pop moments, that has perhaps only grown in impact over the intervening years since its release. Turning evocative production into a virtue, each instrumental part and note given a sense of space that was uncommon in an era of glossy pop. Thus ‘It’s My Life’ is built upon a groove of clicking drum machines, snaking baselines and Friese – Greene’s astounding synths that swirl and squawk above the head.

“It was Tim, on an Oberheim OBMx, but most the others were me on a Roland Jupiter 8, except one we called Tugboat” recalls Ian Curnow the band’s keyboardist in an interview “We try to use synths from the point of view of unnatural instruments. We try to use a synth sound as you would use a Fairlight or whatever – you don’t get a particular string sound where you say ‘oh, that’s obviously a string’, You play with the sound and make it into something that hasn’t been heard before.”

“One-half won’t do,” sings Mark Hollis in the pre-chorus, before the song lets flight into a glorious key change, life-affirming crescendos lifted aloft by firing drum machines, warm tumbling synths, while Hollis’s imperious tone shivers with a wistful impregnable power, ripe with existential yearning. Each note gives voice to a quivering vulnerability and a clinging to hope, embodying the contradictions of life’s constant struggle, alone and part of the crowd all at once (‘caught in the trap it never ends’). Criminally it was a miss on its original single release, only charting at thirteen in the UK chart on its rerelease in 1990.

‘Such a Shame’ clambers into your headspace with synth motifs, robust bass of I played it on my lap and plucked it with a screwdriver – that’s my secret” Paul Webb who recalls “I played it on my lap and plucked it with a screwdriver – that’s my secret!” welded to another fine Hollis vocal, wrought and wistful he sounds like he’s in pain but also bristling with a barely concealed rage: a feeling that he has to change to survive in the face of the obstacles life throws in front of us. The weighty chorus is counterbalanced by retorts “such a shame”.

The song was inspired by Luke Rhinehart‘s The Dice Man, one of Mark Hollis’ favourite books. The lyrics character’s personality changing on the roll of a dice, Hollis remarked it was “a good book, not a lifestyle I’d recommend.” ‘Renee’ meanwhile is all trembling cymbals sumptuous bass and regretful atmosphere has an Avalon like quality, sophisticated suites punctured by synth sweeps and a nagging, dramatic chorus.

Follow up ‘Colour of Spring’ is perhaps my favourite of their records, one that takes from their past but glances towards their future. They began their shift towards the majestic and sparse suites of sound that characterised their latter more experimental albums but still retained a grounding in an anthemic pop communality, in common with the likes of Tears for Fears.

What’s immediately clear from opener ‘Happiness is easy’ is the vivid clarity they achieved with these recordings, with Lee Harris’s dexterous percussion and Allan Gorrie’s twisty baselines and sudden splashes of piano and flamenco guitar providing a backdrop: it has a free (almost)jazz-like quality reflecting Hollis’ increasing passion for Miles Davis and Can, this approach even at this point standing out in a mid-80s music scene that was awash with synthetic sounds. Happiness is anything but easy and that’s the unbearable irony here, Hollis’s vocal is quivering: the lyrics (“makes you feel much older, sublime the blind parade/ It wrecks me how they justify their acts of war”) speak to both existential dread and weighty world themes, the sea sawing chorus balanced off by a queasy children choir, that lends it a sorrowful poignant universality, that is both sad yet offers hope and is perhaps at odds with how illusive Talk Talk could be as a group. At once unsettling and infectious. Embodying pain and pleasure all at once. Nothing is overdone, each part has its space, this is superlative songwriting.

‘I Don’t Believe in You‘ is another overwrought masterwork, fragmented flecks of piano and guitar strums over a strident drum beat and Hollis’ wracked voice, he sounds disheartened, beaten and distrustful here: it’s a theme that would shudder through this long-player.

‘Life’s What You Make It’ is another standalone single, that still sounds as fresh as a daisy. Built on the bedrock of a looping percussive framework of piano runs, that lollop continuously, this repetition has comparisons with dance music or hip hop, the percussion remaining a constant while garnished with elements on top. Baselines are sinuous like tree trunks and drums that hammer the roots further into the ground. This natural imagery is reinforced by the fantastic video, that places Hollis on a piano in the heart of a dark forest.

While a restless riff and Hollis’s vocal interplay is extraordinarily anchored by the central refrain he cuts you in two with extraordinary cries, at once wrought and joyous, introspective and embracing, its the cycle of life, its the duality of everything, the pleasure, the pain, its universal to nature and the human experience.

In a Belgian television interview in 1998, Mark Hollis said of his singing style that “The thing with the vocal is just y’know to, like you’re saying, treat it like an instrument. It’s not there to dominate. It’s just there to sit in the kind of landscape along with everything else, y’know, and it’s kind of like, start from a melodic point of view, then, think about the kind of y’know, the kind of inflections that it should have sound-wise, and similar if you’re looking at a clarinet, at certain notes, there might be a certain kind of way you want to hear that note, that note, y’know sound, so that when you write the lyric you have that as an actual, y’know, block that you must write to. You must write this lyric phonetically in order for it to sing, with a certain way. And then you must write the lyric in a way that, when you sing it, you’re going to have belief in it.”

‘Living in Another World‘ is another key moment from the album, vibrant, the Hammond organs, frenetic harmonicas and driving percussion and a majestic wounded Hollis vocal, trapped in a maze of modern life punctured by exquisite imagery about being ripped apart from the one you love and facing down mortality. (“(Forget)/That even breaking up was never meant/(Forget) But only angels look before they tread”) It produces a rush of traumatic imagery and yet perspective.

Two tracks here point to the minimal seas which Talk Talk would soon swim. The solemn ‘April 5th‘ and elusive ‘Chameleon Day’. Closer ‘Its Time‘ is a weighty recognition of time running out for him, us, and perhaps for humanity? Upon release ‘The Colour of Spring’ was a commercial success landing at number 8 in the UK chart, with EMI now affording them a bigger budget for its follow up. But instead of producing another chart scaling album, as David Stubbs put it in Uncut in 2002, “when they re-emerged, it turned out that they had done what every mega pop band talks about doing but so rarely does – i.e. what the fuck they wanted.

Retreating to rehearse the sessions for 1988’s Spirit of Eden were tortuous and protracted, EMI awaited the finished product, as the group worked far past its deadline, seemingly with no end in sight. Well over budget Hollis refused to allow label heads any advance tapes, and informed EMI that not only would there be no singles from the record, but that the group would be unable to re-create the complex arrangements on-stage so they would be unable live dates in support of the album’s release.

After 14 months in Wessex studios in Highbury London, what emerged was a leftfield masterpiece, that is perhaps their defining record. Moving away from any of their early synth sounds, ‘Spirit..’ was assembled from many hours of improvised instrumentation that Hollis and Friese-Greene had spliced together and arranged. If it’s a concept record it runs through the rising and setting of the sun in one day, with references to the naturalistic world(only aided by James Marsh’s strikingly vivid album artwork), Eden and spirituality, there are illusions to the first days of creation. Upon its initial release, the record was hugely critically praised, but not as commercially successful as its predecessors.

Phil Brown an engineer on the record told the Guardian in 2012, that he recalled sessions featuring “endlessly blacked-out studio, an oil projector in the control room, strobe lighting and five 24-track tape-machines synced together. Twelve hours a day in the dark listening to the same six songs for eight months became pretty intense. There was very little communication with musicians who came in to play. They were led to a studio in darkness and a track would be played down the headphones.” Asked whether Hollis is an awkward genius or a normal bloke? Brown replies: “All of the above! Stubborn, focused, but humorous. In some ways a genius, but it was a team effort – and it was a big, talented team.”

The result was six tracks of unhurried, ambient, adventurous soundscapes that trace a landscape that is as rich and expansive and undulating as it is astounding. Hollis’s subtle, cathartic therapeutic brand of songwriting that carves moments of tranquillity had reached a rarified air. More experimental than its predecessors, this is a record of pastoral moments, that takes time to drink in but once it does it makes an indelible mark. Its visceral elements pushed further by his collaboration with Freise Green have been a huge influence upon the post-rock genre, its suites of ambience a influence on the experimental ends of that sound. It is an extraordinary record.

“Spirit of Eden”, I kind of think that was very much like, in a way where all those earlier albums were trying to get to. And then having got there, I then think the important thing is that, y’know, you either, you either just stop making records at that point because you’ve kind of reached what you were trying to get, or from that point, you seriously redress, y’know, these other areas that you, that you go for.” Mark Hollis

Opener ‘The Rainbow’ rumbles so slowly and quietly into life you almost wonder if its actually started playing at one point, then suddenly a glacial guitar motif chimes and squeals, underpinned by a singular kick drum and pianos, a sense of confusion and disappointment runs across Hollis’s muted delivery. Then a transcendental ambient crescendo warms your face and you are back to silence.

As our late colleague and Talk Talk fan, Nikolai Rainbow puts it better than I could “Mark and Tim Friese Green really pushed the envelope. Halfway through its swirling miasma of dubby bass, swishing cymbals and otherworldly sounds, Mark was stuck what to play in the 8 bars in the middle of the song where a middle with would usually fall, he tried many different tones and permutations of notes before deciding that just one note would do, fed through an amp and splintering hither and thither, feeding on itself and forming a weirdly addictive atonal break that is absolute genius the way the track ebbs and flows is like the slow crawl of nature itself, and makes for a very compelling centrepiece to the album. No one else would ever have thought of breaking the rules in such an obtuse and refreshing way which make it only more special.” Its ripples of sound are pointed for their piercing brevity (“Sound the victim’s song/The trial is gone“). It’s a majestic piece of songwriting.

The gradually blooming ‘Eden‘ that’s burgeoning sound flowers into a moment of vivid clarity on the heels of wonderful brass. ‘Desire’ possess a startling release, the appreciation of space coming into slow focus before a crushing crescendo guided by squeals of everything rushing in its final two moments, its slow/loud dynamics influencing the entire post-rock genre. ‘Inheritance’ trembles with fragility, oblique lyrics perhaps ponder what would happen if we weren’t here and wonders how humanity would treat the earth we inherit?

‘I Believe In You‘ has a brittle celestial tapestry and a stunning vocal performance woven with soul and vulnerability, tender and affirming at points, despite the intensely personal lyrics, you feel like Hollis could be talking to you. But it’s actually a song about his older brother Ed. Ed worked as a manager-producer-songwriter for Eddie and the Hot Rods. He co-wrote the band’s first hit, Talk Talk. By the mid-1980s, Ed had become addicted to hard drugs eventually passing away. Suffused with grief there’s a vulnerability and sublime beauty to Hollis’s vocal tones and the heavenly organs he is bathed in as he sings, as he is consumed by the wastefulness of how his siblings’ light had been extinguished, too soon, it’s unbearably sad. “Hear it in my spirit/ I’ve seen heroin for myself/Is it worth so much when you taste it?”.

St. Vincent aka Annie Clark tweeted upon Hollis’s passing in 2019 “Spirit of Eden saved my Life. To me, it’s divorced from any people or places. To me, it’s headphone music in random cities all over the world.”

“The reason you’re doing it is for the love of music. It’s not, to like, try and get some kind of commerciality.” Mark Hollis

Hollis was famously uncompromising, sometimes tagged “awkward” he saw the work as the most important thing, rare public appearances and interviews, discomfort around press opportunities, he defied conventions of performance in videos see his refusal to lip-sync in ‘It’s My Life’ or the eccentric performance in ‘It’s a Shame‘. Yet he was also known to be warm funny and consumed by his love of his family and Tottenham Hotspur football club.

During the sessions for Spirit of Eden, Talk Talk got into a dispute with EMI, who were unhappy with how long the album was taking to produce and the increasingly uncommercial direction they were going in. Their manager Keith Aspden had attempted to free the band from their contract with EMI. “I knew by that time that EMI was not the company this band should be with”, Aspden remarked later. “I was fearful that the money wouldn’t be there to record another album.” After months of litigation, the band were released from their contract. EMI then sued the band, claiming that Spirit of Eden was despite reaching the top twenty of the album chart, not “commercially satisfactory“, Talk Talk wasn’t the “next Duran Duran” EMI had dreamed of, and the case was thrown out of court.

With the band now released from EMI, without the involvement from the band, the label released the retrospective compilation Natural History in 1990. It peaked at number 3 on the UK album chart and was certified Gold with sales of over 100,000 copies, it eventually went on to sell more than 1 million copies worldwide. ‘It’s My Life‘ was also re-released, and this time became the band’s highest-charting singles, reaching number 13 on the UK Singles Chart. A re-release of the single ‘Life’s What You Make It’ also crashing into the Top 30. Then the label followed this up with History Revisited remix album in 1991.

In 1990, Talk Talk agreed to a two-album deal with Polydor. They released Laughing Stock on the Verve Records imprint in 1991. By now, Webb had left the group. Having halted touring in 1986, Talk Talk had by then morphed into what was essentially an umbrella name for the studio recordings of Hollis and Friese-Greene, with a long rotating list of session studio players (including long-term Talk Talk drummer Harris).

“I can’t imagine not playing music, but I don’t feel any need to perform music and, I don’t feel any need to record music. I’m really quite happy just to play one note, and just to hit it at different volume levels. And just, y’know, see how long it will resonate for before it stops”. Mark Hollis

The sessions for 1991’s final album Laughing Stock were agonizing, Hollis and Freise crystalized their work still further, operating a policy of less is often more, they crafted an even more minimal and less commercial sound than their previous two records, Laughing Stock is littered with moments of genius, allegedly they were striving to capture a “vibe” recordings, each song stripped down to its skeletal form so that you can hear its throbbing heart.

“I like silence. I get on great with silence, you know. I don’t have a problem with it. It’s just silent, y’know. So it’s kind of like well if you’re going to break into it, just try and have a reason for doing it.” Mark Hollis

Opener ‘Myrrhman‘ broods, scratched guitars, mournful horns, strings, fragments of organ swirl in the mix, Hollis’s voice weather beaten the songs theme concerns suicide but is a thing of beauty: the sense of atmosphere is intense, the space vast it hangs in the air like plumes of smoke.

“It sounds like the bloke’s putting his kit together throughout the track”. Hollis explained how the song sets the tone for the record; it “creates a mood from which it then develops from”. Jane Wasser aka Joan as Policewomen says it “has a blues thing that makes me think of New Orleans. Like a big, old house full of ghosts and swirling memories. The spectre-y vibe.”

‘Ascension Day’ gradually consumes, its shifting jazz flecked textures shift from sensitive percussive strokes up a key into sudden bursts of simmering violent guitars and thunderous backdrops which see Hollis set sail into the unknown. ‘New Grass‘ shuffling drums and lucid guitars are like rubbing the sleep for your eyes opening the curtains and letting the suns rays flood in. Glorious.

Although Talk Talk’s last two albums weren’t commercially successful upon release, their influence has only grown in the intervening years. Peter Broderick told the Guardian “a couple of the Efterklang guys sitting me down in 2007, playing me Spirit of Eden and telling me how much of an influence it had been.”

Standing out from many of their contemporaries in an era of heavily commercial and novelty pop, as they evolved from synthesizer sounds to more organic live acoustic sounds over their albums, one that isn’t weighed down by the 80’s productional troupes that date many of their contemporaries records, we still hear the ripples of their sound to this day their ability to craft sparse meditative suites of sound that suddenly enliven or crescendo through a guitar part, woodwind, a percussive rustle, trembling vocal part: its this ability to weave together compositions so rich with intricacy and yet room for each note, their music still influences the sound of music today see acts as disparate as Radiohead, Sigur Ros, God speed You Black Emporer, Elbow, Grouper, Low, Bon Iver, Efterklang, Joan as Policewomen, No Doubt, M83, The Mars Volta, Arcade Fire, Wild Beasts, Anthony Hegarty, Perfume Genius, The Anchoress, Loma to name just a few.

Guy Garvey of Elbow Mojo music magazine that: “Mark Hollis started from punk and by his own admission he had no musical ability. To go from only having the urge, to writing some of the most timeless, intricate and original music ever is as impressive as the moon landings for me.”

Producing a golden run of records up there with imperial phases of Stevie Wonder, Prince, The Cure, Kate Bush and others Talk Talk produced timeless and affecting music with a cavernous depth, emotional heart and sensitivity that feeds the soul, wistful and life-affirming all a once, it recognises and embraces the tenuousness of being and vocalises it in all its dichotomies. These records marked Hollis out as one of the most influential songwriters of his generation and someone who touched people’s lives with the wonder, vulnerability, honesty and depth of his work. Talk Talk turned evocative production into a virtue, each instrumental part and note given a sense of space and breath that was uncommon in the mid-80s.

After a single solo album in 1998, this reclusive man retired from music twenty years ago, to look after his two sons. Cultivating an elusive myth by disappearing from public view after 1998, not playing live or cashing in on his success, Hollis was that rarity an artist on a major label that did things on his own terms.

As Graeme Thomson observes in a piece on his legacy: “Hollis’s distaste for image-building and promotion worked against the band at the time; now it’s become an advantage, feeding into the perfect myth of an artist who achieved all he wanted and then walked away.”

To listen to Talk Talk is to be transported to another place, an escape I can listen to their albums over and over and be taken out of myself, its music that transcends and offers a hand of hope in a sea of the often unseen, everyday struggle of life. The unforgettable talent and spirit of Mark Hollis and the work under the umbrella of Talk Talk will continue to echo down the decades. Talk Talk are one of Britain’s greatest bands.