Over the course of the last few weeks, as covid-19 has continued to take a devastating toll, people’s appreciation of the NHS, unsurprisingly, has gone up. It shouldn’t have taken a global pandemic to make people realise how crucial the NHS is, of course, but even those who, perhaps never having had to use it themselves, didn’t comprehend just how vital it is have now come to understand its value. If it is at all possible to take anything positive from dark times such as these, maybe it’s that when this is all over, people’s thinking over what is really important will be realigned a little, that people will be more aware of the institutions that truly need protecting in this country, and be more appreciative not only of an institution as great as the NHS, but also be left with a greater recognition of how important people whose value may previously have been unrecognised really are. Not just doctors and nurses, but also bus and train drivers, farmers, shop workers and cleaners.

That all remains to be seen of course, but in the short term at least, people are genuinely appreciative of frontline workers in particular and, wanting to show this appreciation, have done so in many ways. Hundreds of thousands of people have offered their time and energy by volunteering in various capacities, while many have donated to crowdfunding efforts to provide staff with much-needed PPE.

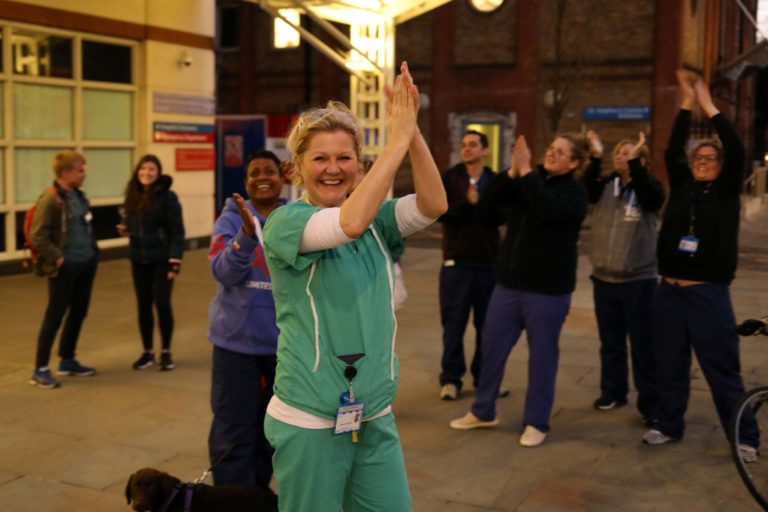

Another way has been to step out of their houses at 8pm every Thursday since lockdown began to show their gratitude by clapping. Not just for NHS staff, but for other carers and key workers. #clapforcarers has trended each time, and, propelled by Twitter and Facebook, thousands have taken to their front step to join in, and a lot of the footage has been genuinely heart warming.

As with anything driven by social media, however, a downside has quickly become apparent. Not content with simply showing respect themselves, a trend has developed for ‘shaming’ those who choose not to join in. The response to any non-participation has been to take it as read that anyone who doesn’t turn out to clap, by definition, doesn’t appreciate the NHS and other key workers.

Some people not participating may indeed not appreciate key workers, and may spend each Thursday evening turning the sound on their television up, whilst shaking a clenched fist vaguely in the direction of their street, but the assumption that this is the case with every individual is a troubling one. Who knows why any individual or household may decline to join in? Perhaps some regard the act as virtue signalling that achieves little. Someone not clapping may be a frontline worker themselves, but not wish to join in with public acts like this due to, say, chronic shyness. Maybe they choose to show their appreciation by consistently voting for the party they feel is best placed to protect health and social care, or by donating money to appropriate causes. Maybe they simply choose to show their support in their own, private way.

But a growing hysteria around non-participation is evident, and one suspects that, even if these hard-line clappers knew anybody’s reasons for not opening their door bang on 8pm, it wouldn’t be good enough for them. If a neighbour isn’t showing appreciation in the prescribed way, then it simply isn’t valid.

It’s an unpleasant side to what should have been a straightforwardly pleasant act, and an example of how we can no longer simply engage in public displays of…well…anything, without attacking those who choose not to engage, as well as engaging in ever escalating one-upmanship to prove who is the most engaged/grieving/outraged. Turning #clapforcares into a means to shame other people or using it as a means to escalate an existing neighbourly dispute, as I suspect is happening in some cases, instantly offsets any positivity the initial act itself may have generated.

Across social media I have seen people judged, insulted, condemned and, in one case, have even seen someone tweeting the house numbers of people on their street who didn’t take part. Quite what the intention behind this was is unclear, and it feels like something of a stretch to suggest this is a first step towards some sort of pro-carer vigilante justice where non-clappers are dragged from their houses to be tarred and feathered in the street, but it left a bad taste.

It’s easy to be left with the feeling that some people simply won’t be happy even if everyone on their street took part. The next stage of this shaming will be for these people to shame their neighbours for not clapping loudly or enthusiastically enough. And if they do increase their claps-per-second ratio to a level deemed sufficient by the clapping extremists, or they clap until their hands are sore and bleeding, they will then be criticised for not bringing out the utensils to bang, and perhaps then for not bringing out the utensils.

‘Sorry, Carol, but the sound emitted by that le creuset casserole dish is just too dull for my liking. You need a good old fashioned frying pan, or you don’t love our NHS like I do’.

It all brings to mind the shift in attitudes around wearing poppies. For as long as most of us can remember, wearing a poppy was a simple, symbolic way to show our respect for those who had died during World War One and subsequent wars and conflicts, as well as a way of raising funds for the British Legion. In recent years however, even the simple act of remembrance has been complicated by people for whom no expression of respect is ever quite respectful enough.

It’s hard to pinpoint exactly when this ‘my grief is bigger than your grief’ began, but increased immersion in social media has undoubtedly played a part, as has the symbol disturbingly being increasingly co-opted by the far-right. Poppies used to be poppies, mostly one size, small enough to pin onto your shirt. People were rarely shamed for not wearing one, and if anyone was casting a critical eye at all, then simply wearing one was enough. Now, unless we are wearing a poppy the size of a tractor tyre, we are still not being respectful enough for some.

What was once a solemn act of respect and remembrance was hijacked by a baffling brand of poppy fascism, one that has resulted in many people now choosing not to wear one at all.

Just as choosing not to wear a poppy, for whatever reason, doesn’t mean you don’t care about those who died during wartime, choosing not to clap, bang your pots and pans or blow your whistle doesn’t mean you don’t care about key workers.

The true test of how much people value the NHS when this horror is all over will not be how many times they clapped, but how they vote in future. With no election likely to happen any time soon, however, for now, #clapforcares is a nice way of showing appreciation. It means something to those on the front line, and to those being treated by them, and I’m in no way denigrating the act itself.

It’s an example of people coming together at a time when we have to stay apart, and when we can use every last drop of positivity we can find.

So let’s not turn a positive into a negative by shaming Geoff at number forty eight, just because he chooses to exercise his right not to participate.

Let’s not ruin a good thing, people