It is now thirty years on from 1994. The story of 1990s’ music in Britain is well documented and defined, a retrospective tale that fuels a nostalgia industry that sells us a potted view of “scenes” of the time, with playlists, reissues, and festival line ups. But in reality the story of the ‘90s is far more diverse, more eclectic than retrospectives can allow, because there was brilliant music of all different kinds and genres in the ‘90s (plus a lot of very bad too).

I have always been a fan of artists that used strings and extra instrumentation and throughout the ‘90s there were records that used such arrangements, whether they’re crate digging using samples to splice with different sound to create something new, or adding synths to recreate the sound. Whether featuring one player, a quartet or a full orchestra, whilst live instruments clearly have a character it’s hard to recreate, personally, I don’t particularly care if strings are created in a studio or by an orchestra as long as they sound good. At their best they can enhance a sound palette, adding textures and notes that a normal set up cannot do, pushing sounds and songs to a wider scope. At their worst they can be shmaltzy, cheesy and unnecessary, but we will get to that.

So to tell an often untold story, I have been interviewing some of those artists and acts and the often behind-the-scenes musicians and composers who helped arrange and orchestrate some of the best records of the era. It’s the fascinating story of musicians who were eager to augment their sound, who as well as mining British music lineage also looked beyond these shores for influence; who spliced samples to create a bricolage of sound; who used the innovative advances in technology to recreate string sounds. They were funded by ambitious labels around the mid-part of the decade who could afford full string orchestras, who could take it further to try to outdo their rivals, and for a short period gate-crashed the charts and the mainstream.

This is their story, this is their symphony for the best, most forgotten and occasionally worst arrangements of the era. By the end of the ‘90s the bandwagon had careered off the road and into a ditch, and during its pre-millennial malaise it had faded out with a whimper. But the use of strings in pop, independent and dance music endured and as the 2000s’ digital technology was used to recreate orchestration, even from home, the sound of strings from the ’90s still retains a time capsule character. I have also picked out some of my key examples of string-led pop songs of the 1990s.

The well told “Britpop tale” of the mid-part of the period dominates the narrative but what of the outsiders and the acts that predate and never did belong to it? Whilst the influence of George’s Martin‘s work with The Beatles and the re-use of Mod iconography was indelible and has been well documented throughout the decade as Suede biographer David Barnett says at the time “every band wanted to sound like the Beatles“, but musicians and music fans also looked beyond these shores and beyond the ‘60s for inspiration too, from classical music, to the scores of John Barry and Ennio Morricone, to Phil Spector‘s Wall of Sound and Motown, and the The Beach Boys, to Scott Walker and Serge Gainsbourg, hip hop, electronica and club culture and beyond.

Independent and small label artists had been bubbling under through the early ‘90s; there were brilliant acts of all kinds at that time. The early part of the decade saw independent label bands find favour, labels like Heavenly, Rough Trade, Echo, Mute, 4-AD, Warp, and Creation housing acts that pushed sonic boundaries (My Bloody Valentine, Spiritualized, Lush, Catherine Wheel, Cranes, Slowdive et al), the crate diggers of the hip hop, the dance music pioneers of the trance and rave scenes.

“There were enlightened A&R guys around who would be up for just letting the band try something, not necessarily with a view of what’s going to be a hit single or whatever,” recalls Audrey Riley, an accomplished cellist and arranger who spoke to me in depth about her work with her quartet on some key records of the ‘80s and ‘90s including, The Smiths, The Go-Betweens, to New Order, Swervedriver, Blur and Dubstar and many more to this day.

“There were some really good people around. There was the Echo label, the guy who ran that had a real vision. 4-AD, Mute, and then there was Geoff Travis of course, I know that he got reined in and that was really sad because actually, Geoff was responsible for some amazing experiments in music and, in my view, you can’t have successful records unless somewhere else there’s some experiments going on,” Audrey Riley tells me.

Originally released in 1989 and sticking around in the charts at the beginning of the 1990s, Electronic‘s ‘Getting Away With It’ had its trademark keyboard motif going hand-in-hand with a memorable, fluid and full orchestral arrangement from Anne Dudley. Dudley’s favourite composition she worked on, it marries the infectious bittersweet melodies of Sumner and Tennant, the guitars of Johnny Marr, synth textures of Chris Lowe and an elegant arrangement, with the final three stings offering a fantastic full stop to the track. Folklore says the lyrics written by Neil Tennant are about Morrissey. Above all, it’s a fantastic pop song.

Dudley is a keyboardist, composer and arranger who made a mark on string arrangements on pop records and soundtracks throughout the ’80s and ’90s and beyond from working with the Art of Noise, Frankie Goes to Hollywood to ABC, Pulp and Pet Shop Boys. She also scored films like The Crying Game and The Full Monty amongst many others; she is another unheralded figure in music.

Talking about Electronic’s elegant ‘Getting Away With It,’ David Stubbs noted in the Guardian, “her accomplished arrangements and classically-trained playing have lent these artists an aura of finesse they could never have achieved alone. Without Anne Dudley, ABC’s The Look Of Love would be a mundane sequence of chords plodding up a keyboard in search of a flourish.”

Released in January of 1990, Sinéad O’Connor‘s single ‘Nothing Compares 2 U’ is a startling and heart-breaking track from the tail end of the year. From a artist with a striking voice who shared her vulnerability, she reworked this Prince song along with her producers into an incredible moment in pop music, one that Sinéad, who sadly passed away last year, will always be remembered for.

It turns out the string sound was created using a combination of keyboards and samplers. This light touch string sound that envelopes and gives O’Connor space to emote, adding a dramatic and mournful atmosphere to the track. It was created by drummer and Japanese acid jazz virtuoso Gota Yashiki. Previously he had played with the Tokyo-based reggae/dub outfit Mute Beat and, together with fellow band member Kazufumi Kodama, formed the duo Kodama & Gota. During the late ’80s he also worked on records for Soul II Soul. The producer of ‘Nothing Compares 2 U’ Chris Birkett would later describe him as “a genius” for his work.

“The engineer was a female named Arabella Rodriguez, who had also recorded and mixed Soul II Soul.” Yashiki told Sound on Sound “At first, we did pre-production at Nellee’s house, where I did most of my work using an Atari with Notator software and an Akai S1100 sampler. Then we began recording at Pink Floyd‘s studio, Britannia Row, where I did some overdubs — a little drums and playing keyboards for a cello part. The track was really slow, and the bass drum and snare drum sounded great, but the programmed hi-hat just wasn’t working. So I asked if a hi-hat and cymbals could be hired, and I played those live. Then the cello part still wasn’t gelling together, so I overdubbed that at Britannia Row using the Akai sampler with a keyboard.

“I wanted to be really sure that everything felt right, and this meant the strings had to sound natural, which I think they do.”

Another key record in this period was ‘Unfinished Sympathy’ by Massive Attack. Released in 1991 it was the second single from the band’s debut album, Blue Lines. Shara Nelson had met the members of Massive Attack when they were part of the Bristol sound system collective the Wild Bunch.

Massive Attack, Nelson and Dollar worked on the song during a jam session, and using a drum machine, keyboards and Nelson’s vocals it became a rolling piece of revelry. The title ‘Unfinished Sympathy’ – was a pun on Franz Schubert‘s 1822 ‘Unfinished Symphony’ – and during this session, Robert Del Naja said: “I hate putting a title to anything without a theme, but with ‘Unfinished Sympathy’, we’d started with a jam… The title came up as a joke at first, but it fitted the song and the arrangements so perfectly, we just had to use it.”

‘Unfinished Sympathy’ is a hymn to heartbreak featuring the soul tones of Horace Andy as well as Shara Nelson. It’s all filtered through the trip hop prism of trippy beats, samples and unobtrusive string arrangements – this was a watershed moment for both.

The orchestral section was originally played on synthesiser, but, according to the Massive Attack member Andrew Vowles, “The synth sounded too tacky, so we thought we may as well use real strings. The orchestra definitely changed the feeling of the song, making it heavier and deeper with more feeling.” Dollar contacted the music producer Wil Malone to arrange and conduct the strings, which were recorded in Abbey Road Studios, London. According to Vowles, the orchestra “were really good [but] it took them about five takes to do it because they were slightly behind the beat”.

“I remember, the track was originally eight minutes long and they let me hear many demos of the song; all sorts of constructions and different ways of doing it. I asked them what they had in mind for the string arrangements of the track and it was Massive’s producer Jonny Dollar – he was highly responsible for putting together the track – who said: ‘do what you feel like’,” remembers Wil Malone for the Abbey road website.

“The reason for inclusion of the string arrangements was to be supportive. In my view, in pop music, strings have to be supportive to the vocal, although they also have to give a boot and a sense of tension. If you have a rough track, it’s good to have the strings as a classical contrast sound so that you create a tension, a suspense going on all the time between the roughness of the track and the purity and classical feel. In pop music you’re usually working on a track with bass, drums, guitar, synthesizer, vocals and the strings have to blend with all that. My approach for Unfinished Sympathy was that it’s a really open track: basically it’s just a groove – keyboards, and a great vocal by Shara Nelson – so you just let it drift, just let it chill.”

The strings particularly have a billowy grandeur on the final record. “With most string arrangements that I do, the strings are ‘put back’ in the mix. In other words they are so quiet you don’t really hear them, or they’re mixed up, so that you can just hear the top lines; but on Unfinished Sympathy, the strings are exposed. You can really hear them and I think that makes something different. The string arrangements were played by 42 session players in Abbey Road Studio One. I wanted to make the sound rich so that it vibrates in your chest and stomach, but to also keep it cool, so not so much vibrato – hit the bar lines very accurately. When you are writing, descriptively, in classical music there are emotions that you want the orchestra to have or play, but in pop music that isn’t true. There is no point in writing instructions like ‘dolce’ unless it really means something; basically it is a different way of writing for strings in pop music as you’re writing to a mix, you’re trying to blend your sound into the sound that is on the track.”

According to reports, Massive Attack had not taken the cost of the orchestra into account when planning the budget for Blue Lines, and had to sell their car to pay for it.

“I remember the tracks R.E.M. were producing at this time were really influential,” remembers Audrey Riley. R.E.M’s 1991 album Out of Time was woven with lush orchestral elements arranged by composer Jay Weigel: cello, violins and woodwind are garnished throughout, typified by cooing melodies of string-led instrumental ‘End Game’. Out of Time has the qualities of a stage show, where each guest plays a part. The band swapping instruments and bringing “non rock” instruments to the party including memorably on their best known song ‘Losing My Religion‘ that is decorated by Peter Buck‘s fantastic mandolin riff, while memorably ‘Half A World Away’ pairs longing vocals, staccato strumming and gorgeous string sweeps that lend the song a cinematic grandeur.

For their follow up 1992’s classic album Automatic For The People, the grand folk-inspired gothic framing was arranged by former Led Zeppelin bassist John Paul Jones. Touchstone tracks include ‘Drive’, ‘The Sidewinder Sleeps Tonite’, and particularly ‘Night Swimming’ with its tender reminiscences of Michael Stipe added to a piano motif: cellos, violins, oboes and a winding accordion is particularly touching.

“Scott Litt had heard some old string arrangements I did for Herman’s Hermits in the 1960s, so they got in touch,” Jones says. The four demos were duly dispatched, along with “a nice little hand-written letter from Michael.” He was impressed and agreed to take on the assignment. When the composition was complete, R.E.M. and Jones convened in Atlanta’s Bosstown Studios to record the parts with the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra, conducted by George Hanson.

Elsewhere in 1991, P J Harvey‘s ‘Dress’ from her debut album Dry, the sawing attack of the double bass added an impressive heft to Harvey’s whip-smart vocals. The thrilling guitars bristle with the agitation – a tale of a woman wearing a dress to please a man, who doesn’t appreciate it, and ends up resenting the effort.

James who had been joined by violinist and guitarist Saul Davies (who was recruited from an amateur blues night), keyboard player Mark Hunter, and trumpeter/percussionist Andy Diagram (who had previously played with The Diagram Brothers, Dislocation Dance, The Cotton Singers and Pale Fountains) for their third album Gold Mother and scored a big hit with the anthemic indie-disco standard ‘Sit Down’ and in 1992 released the howl of ‘Born of Frustration’ from the album Seven, with its accompanying keyboards, dancing melodies and horns which would become their trademark.

Also, Bryan Adams clogged up the number one spot for a ridiculous sixteen weeks, with dire power balladry of ‘Everything I Do I’ll Do It For You’, unfortunately.

Serge Gainsbourg was a key influence upon the artists in this period, especially after his death in 1991, his records were picked over for samples and influence, particularly the looping sound of his ’60s singles particularly ‘Je t´aime moi non plus’ with Jane Birkin, and the orchestral pop of his album Historie De Melody Nelson: “He’d already become a bit of a hit with crate diggers with samples turning up in unlikely places such as De La Soul records,” remembers excellent journalist Jeremy Allen who wrote the book Relax Baby Be Cool: The Artistry And Audacity Of Serge Gainsbourg. “More than anything though it was the rediscovery of Histoire de Melody Nelson that became so influential – I think these rediscoveries are often incremental, word of mouth affairs. That record was actually a flop when it came out in France in 1971 – it only sold about 20,000 copies on release and didn’t go gold until 1985 in France. It really entered the pantheon after his death which I’m sure would have pleased him. The fact it bombed commercially hurt him and I don’t think he ever really recovered, although commercially he was yet to have his biggest successes. “

De La Soul spliced two Serge samples into 1991’s landmark De La Soul Is Dead, an album recorded before his passing. Tapping into the funky sound within ‘Les Oubliettes,’ working it into ‘Talking Bout Hey Love’.

The looping sound of Gainsbourg’s ’60s pop work and ’70s orchestral sounds, were cited as a influence upon many ‘90s acts including Massive Attack, Tricky, Stereolab and Portishead who took the influence and and reinitiated it into their sonics. “You can definitely hear that influence writ large across the ‘90s, but as I say, it really coincided with the culture of taking strings and textures from other records and doing something else with them. It’s important to state that Gainsbourg was very reliant on his arranger Jean-Claude Vannier, who did some extraordinary work during the ’60s and ’70s. Gainsbourg took a lot of the credit – and the writing credits too – which Jean-Claude clawed back a little bit in recent years, getting some co-writes and royalties that he should have been entitled to. Neither could have made a record as great as Histoire de Melody Nelson without the other one, and it certainly couldn’t have existed without Jane Birkin, who was the inspiration.”

Another outfit influenced by Gainsbourg were Saint Etienne, a group made up of former music journalists and crate diggers Bob Stanley and Pete Wiggs who were later joined by singer Sarah Cracknell. Following up their hit reworking of Neil Young‘s ‘Only Love Can Break Your Heart’ in the previous year, Saint Etienne released the marvellous single ‘Nothing Can Stop Us Now’ on Heavenly records in May 1991. Lifted from their debut Foxbase Alpha album, the song is a magpie pop delight, based on a chopped up and looped sample from Dusty Springfield‘s recording of ‘I Can’t Wait Until I See My Baby’s Face’. Joyously and affectionately working it into a heady bricolage of their affection for Northern Soul and ’60s records, it’s lush post-modern sounds is underpinned by a ’90s clubby beat and decorated in sunny horns, glistening guitars, delicate strings and chirruping flutes. With Cracknell’s delicate monologue unfurling into a wonderful chorus, it sounds positively radiant. Their 1994 album Tiger Bay would fully realise their sound with instrumentation and strings brought in to lend warmth to the recordings, one of the standout moments is the lush ‘Hug My Soul’.

Spiritualized’s 1992 Lazer Guided Melodies saw Jason Pierce explore the universes of sound harnessing meticulously arranged strings and horns to craft swelling soundscapes, ripe with details, space rock guitars and woozy and intimate melodies, this was a head music album with an adventurous grandeur. “If there’s a rush to be got from a church or religion, hopefully you can get it off our music,” Pierce told Melody Maker before the arrival of 1992’s Lazer Guided Melodies. He was true to his word, non-electric components added by the strings of the Balanescu Quartet. See the transportive ‘Step into the Breeze’ with it’s enveloping suite of strings gradually rising to an awe inspiring crescendo. Pierce later said the album cost £3800 to produce. He would go on to push the envelope further on the 1997 album Ladies and Gentlemen We Are Floating In Space, more on that later.

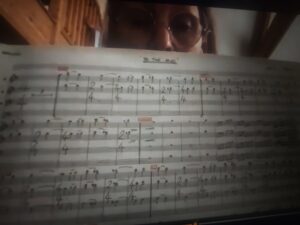

“In my very earliest arrangements there were no computers, nothing really. I think for my first few I used a Philips double cassette recorder and the piano, and then just sitting and writing out a pencil score, literally, then giving parts to the quartet,” recalls Audrey Riley. “The very first one was for the Go-Betweens on ‘Liberty Belle (The Wrong Road)’. So I’d get asked, will you come to the studio? I would write an arrangement that we were going to record, but because I play the piano but I play slowly, the very first time I would have heard the arrangement for real, often, was when we played it in the studio. Hearing it for the first time at the same time as the band. Before that it was all in my imagination.”

“That’s how it was for ages, until I started getting Portastudios and keyboards and I could multitrack my ideas. Then later I used a reel to reel tape recorder, so I could hear my ideas over the track that I’d been sent. My brother sorted out a system for me with an R8 and and so on. But for a long time, it was guesswork and paper scores and then it would be the quartet in the studio that would bring it to life. And because we’ve been working together for so long, they know exactly what I want now. So that they just turn these scribbles on paper into beautiful music. So no, it’s very far from being just me, it’s the quartet together who have turned it into music. So the Quartet are Chris Tombling (violin), Sue Dench (viola), Leo Payne (violin) and myself. We played live quite a lot in the ’90s (with Terrorvision, Feeder, Moloko). Most recently we’ve been playing live with Birdy.”

“For me in the ’90s we weren’t well off you know, most of the time, but it was really exciting and I want to thank you actually for sending me that list of tracks yesterday because it sent me into my catalogue and the list of arrangements over the years.” Audrey Riley tells me, fascinatingly, as she shows us handwritten scores for records spanning decades. ” The scores are all here in the corner of my studio.”

“In the mid ’90s onwards, for about 10 years, there were smaller record companies who hadn’t much money, but enough of a budget to take a chance on string quartet with a band, who were probably going to sell a few albums,” remembers Riley. “So even with a budget 500 quid, for that they could get maybe an arrangement and a string quartet in a studio, on a track or two.”

“There would be types of artists that you’d be working with in the ’90s. I don’t really call it shoegazing but more independent rock (like Swervedriver, Catherine Wheel, Lush) where you’d be squeezing a string quartet in alongside all of the distorted guitars and experimentation, this fantastic music in Livingston or Church studios,” Riley recalls.

“Then there would be the more synth based bands who are working with samplers and keyboards and very tightly playing to the click, everything really organised and very produced and that would be New Order, Dubstar and Blur.” Riley worked on arrangements for New Order’s Republic in August 1992, including the mournful single ‘Ruined in a Day’, that matches electronic synth sounds and click beat with Riley’s long floating cellos and her quartet’s sensitive framing.

David Barnett told me “the fact the music industry was quite rich facilitated a lot of this – it’s incredible to think that Menswear got an orchestra but The Smiths never did!” he remembers. ” The Kick Horns are crucial here. They played on EVERYTHING but most significantly on Blur’s Popscene (1992) which is arguably the first (’90s) Britpop single. The Kick Horns were session players who added horns to alot of the key records of the era.”

In 1993, Suede were the most exciting new band in the country playing ‘Animal Nitrate’ to a nonplussed audience of penguin-suited Brit Award executives. They always had a fascination with orchestral sounds, even from the release of their debut album, it’s something they would go onto explore in greater depths on its follow up Dog Man Star. David Barnett recalls, “I think the first song that had proper strings was probably ‘Sleeping Pills’ – interestingly that was earmarked as the third single quite early on, until they came up with Animal Nitrate and everyone went “that’s the hit!” – but it’s interesting to speculate how Suede might have been perceived if they had gone down the original route …”

Hailing from Nottingham and wearing dusty second hand suits, Tindersticks crafted intimate, well-worn bedsit epics influenced by the laments of Scott Walker, Serge Gainsbourg’s more luxurious works, smoky jazz and the muted work of American artists like Low. Their live performances were often augmented by large string sections and even, on occasion, a full orchestra.

Lifted from their debut album, their 1993 single ‘City Sickness’ is a key example, seductive and enveloping of baritone lead Stuart Staples‘ lyrics are literate and achingly personal and daubed in deep melancholia, pathos and humour. This is a man who has felt pain and can barely express it; he sounds despondent, barely able to exhale, yet reveal inner monologues, big city alienation, heartbreak and tiny fragments of life. Featuring a rich palette of instruments produced by Lee Hazelwood, including strings and woodwind it swirls up brilliantly in its final section. It has a a fine and richly detailed character, a mini symphony on a down-at-heel budget, more likely to be played on battered pianos, tea chests and knackered out violins. These compositions were aided by the orchestrations of multi-instrumentalist Dickon Hinchliffe (who left the band in 2006). It’s a sound they would build on with with their excellent self titled album in 1995 and Curtains in 1997, more about these in part two.

Released in 1993 ‘Play Dead‘ by Björk is another of the standout string-led pop songs of the era, originally written for a film called The Young Americans it would appear on an updated version of her first album debut. Produced and originally written by David Arnold for his first score, he draws a grandly cinematic arrangement of strings with three pointed notes around this head-spinning collision of the bold beats of Björk’s debut album and her incredibly emotive vocals that inhabit the feeling of acting numb to prevent trauma. “The character in the film was suffering and going through hardcore tough times and at the time I was at my happiest,” Björk explain. “In the film, he had a girlfriend who just wanted him to be happy and in love and he just couldn’t get his head around it. It was just me trying to imagine what he would say to her. Things he never actually said to her in the film but things he would have said to her”

David Arnold said: “… I had written a song called ‘Play Dead’ for my very first film The Young Americans and I wrote that after seeing Tori Amos do a songwriter’s showcase in London before she was well known. … So I went home that night wanting to write a Tori Amos song, and I thumped out what became ‘Play Dead’.” The final version was written by Arnold, Jah Wobble with Bjork adding words and song writing collaboration,

‘Play Dead’ would be included on later versions of Björk’s debut album that she produced with Nellee Hooper it also contains other innovative arrangements, particularly ‘Venus as a Boy’ that uses ‘Bollywood’ strings and twinkling tip-toeing tablas of collaborator Talvin Singh, as the backdrop for her doleful narrative. Mixing a range of influence from club culture and electronica to prog pop and folk sounds she told Time magazine: “As a music nerd, I just had to follow my heart, and my heart was those beats that were happening in England. And maybe what I’m understanding more and more as I get older, is that music like Kate Bush has really influenced me. Brian Eno. Acid. Electronic beats. Labels like Warp.”

The Divine Comedy is an ensemble founded in 1989 by Neil Hannon who moved from Derry in Northern Ireland to London in the late ’80s, inspired by Noel Coward, Burt Bacharach, Hal David, Ira Gershwin, Cole Porter, Jacques Brel, also early Scott Walker. With their second album Liberation in 1993 they began to carve out their distinctive and charming chamber pop sound delivered with a literate, arched eye brow, teaming up with co-producer/drummer Darren Allison. As well as the literary references ‘Bernice Bobs Her Hair‘ is recalls a short story by F. Scott Fitzgerald; ‘Lucy’ features William Wordsworth poems put to music. It’s the track ‘Your Daddy’s Car’ that’s perhaps the most indelible, a suite of plucked cellos and violins, and Quentin Hutchinson‘s French horn framing bountifully this bouncy melodic tale of mischievous yet bittersweet escape. It’s a sound he they would develop further on subsequent albums.

There is a retrospectively retro “Britpop narrative” of fresh faced kids wielding perky singalong melodies of caricatured British lives with guitars to the fore, Select Magazine, The Good Mixer in Camden, Pulp at Glastonbury, Oasis vs Blur, Geri’s Union Jack dress, Noel’s handshake with Tony Blair, Knebworth and then it was pretty much, over.

But this simplistic rose-tinted narrative ignores how this wave of bands started and it was nothing to do with Union Jack flags or lads, these were actually a series of outsiders, independent bands. Suede, Pulp, Blur, Denim, Saint Etienne were trumpeted on the “Yanks Go Home!” front cover of a 1993 edition of Select Magazine as being at the vanguard of a new “Britpop” wave (a name first used for the UK music scene back in the ’60s) by journalist Stuart Maconie. But beyond Blur it was an ill-fitting description for a mainly “English” group of acts that didn’t fit into this jingoistic mood anyway; instead they actively rejected it. For me, like most “waves” it peaked musically prior to its commercial height anyway and the constant rehashing of this period of a few years, obscures the breadth of sounds in that era.

Looking back on that issue of Select, in retrospect what was meant as a playful jab at grunge and the American alternative music that dominated the airwaves in the early ‘90s, (this was the same year that Kurt Cobain passed away), and this grouping of a set of new bands of different kinds from this country looks, well, a little silly, and worse, this idea wrapped in a Union Jack harks back to an outdated and caricatured “British” psyche with its reverence for a faded, Dad’s Army view of British Empire with all of its privilege, contradictions and shameful past. Whilst its initial success was fleetingly exciting and chimed with a national mood, it later become a byword for simplistic anthems. Others argue its illusions to a nostalgic Britain that never existed anyway and overly nationalistic attitude sowed the seeds for Brexit.

By the mid part of the decade labels had more cash, and bands began to compete with each other for bigger arrangements. By the end of the ’90s, string sections were seemingly bolted onto every ballad you heard on the radio. It had become a parody of laddish festival and football terrace style singalongs that followed in the slipstream of Oasis, but more of that later.

Sheffield’s Pulp had been ploughing their own furrow throughout the ’80s and early ’90s to not as much attention apart from that of Fire records and John Peel. Influenced by Serge Gainsbourg, and Roxy Music, Pulp sardonically skirted the line of bedsit glamour, and ’70s kitsch, and in Jarvis Cocker they had a wiry, enigmatic frontman who used wryness, overt at times sexuality, and humour offering you a window into bedsit heartbreak and tiny moments of beauty in working class lives.

They were joined by violinist/guitarist and songwriter Russell Senior in 1987 and began to expand their sound live and on record. In 1991 they released the brilliant ‘My Legendary Girlfriend‘ that hinted at their potential and adds an atmosphere with synth strings. On its parent album Separations, Senior plays violin with the attack of a baroque classicism on the title track; the string sound on ‘Countdown’ is actually a cello sample.

Released in April of 1994, on their excellent fourth album His’n’Hers Senior plays violin, most notably on the rising sexual tension of ‘Acrylic Afternoons’ about the snatched secrecy of an illicit affair behind twitching curtains, drawn vividly by Jarvis’s breathless delivery. Senior also played it on ‘She’s A Lady’ live, but criminally that part wasn’t used on the record.

Serge Gainsbourg’s passing in 1991 led to reappraisal in this country. On records like ‘Babies’ Jarvis Cocker shows off why he is a particular devotee. His wry humour found in the shock and tales of sexual encounters, taboo and thwarted desires, a knack he may have also found in Gainsbourg records. It tells the story of a teenage boy who hides in his sisters wardrobe who overhears his older sister with a boy in her room, sparking his interest in girls. “‘Babies’ is just a thing you get up to when you are fourteen and certain things are still taboo and you get into situations because of curiosity.” Cocker told Poptastic fanzine.

“You can definitely hear it in Pulp – Jarvis was clearly besotted with Serge,” Jeremy Allen explains. “You don’t hear that sort of overt sexual imagery wrapped up in a bit of class war like on I Spy anymore do you?” Pulp would hit their commercial peak on Different Class, more on that later.

Luke Haines is often credited as an influential figure in the early wave of British bands emerging in the early to mid ’90s, wielding “the celloist” James Bradbury (as he describes him in his book Bad Vibes: Britpop and my part in its downfall ) and influenced by the likes of the Velvet Underground, his band the Autuers released their first single ‘Showgirl’ in 1992. Their debut album New Wave followed in 1993 and is regarded by many as the scene’s first album. 1994’s Now I’m a Cowboy took their sound up another level spawning perhaps their best single ‘Lenny Valentino’ with its twin guitar and cello stabs, breezy percussion and lip curling delivery, it’s vivid and literate. In Haines’s view, Britpop could have been creatively interesting, but there came a tipping point when a dumbing down took over.

“I felt I was up against a rollercoaster of stupidity. Instead of The Incredible String Band and Interstellar Overdrive, they were harking back to Freddie and the Dreamers. Even Oasis were about as dangerous as Herman’s Hermits. It wasn’t oppositional. All those bands were very on-message. They were all keen to be seen as top of the class and part of the music industry.”

Suede‘s Brett Anderson actively spoke out against having a Union Jack transposed behind him. Anderson deliberately distanced himself from the so called “Britpop” scene, which prompted his relocation to Highgate. “ I liked to throw these twisted references to small-town British life into songs” he told The Guardian.

” This was before we had that horrible term Britpop. We were never really at the party, and Britpop was like a big party: people slapping one another on the back and getting beery and jingoistic.” He told the Guardian in 2008 “We could not have been more uninterested in that whole boozy, cartoon-like, fake working-class thing. As soon as we became aware of it, we went away and wrote Dog Man Star. You could not find a less Britpop record. It’s tortured, epic, extremely sexual and personal. None of those things apply to Britpop.”

“My Life Story were very influential on the whole strings in Britpop world. I have a feeling that they played the music on Morrissey and Siouxsie‘s 1994 track ‘Interlude” mostly forgotten but massively influential single of the time …” points out David Barnett..

For Suede’s second album Dog Man Star, released in 1994, Anderson and Butler had been heavily influenced by Scott Walker‘s largely Wally Stott-orchestrated Scott 1 – 4, records. As the Quietus pointed out they pushed further away from the pop music of the era and plunged deeper into existential epics; “Walker’s people sang silent songs and dreamt all day just like those in Anderson’s. One album of Walker’s was a particular Anderson favourite, his third, which included not only ‘Big Louise’ (“guaranteed goosebumps,” says Anderson).

“The important thing to note here is that Brett only got into Scott Walker after Suede kept getting compared to Scott Walker – specifically in reviews of DMS but also things like The Big Time,” remembers David Barnett, “so he only retrospectively became a fan, although a big one!”

Much was mentioned about the Scott Walker influence, which was indelible, yet Anderson’s father’s love of classical musical also seeped through these recordings.

“I would say Brett’s Dad (Peter Anderson) was probably a bigger influence early on – he was a massive classical music fan,” explains Barnett. In Anderson’s first book he describes the “deafening roar” of his father’s classical music. Wagner, Berlioz, Elgar, Chopin and the ubiquitous inescapable Liszt.” He says his own “musical education must have been forged in this turbulent crucible.”

“Brett and Bernard were both very ambitious and keen to bring in outside musicians,” Barnett continues. “The Flugelhorn on The Big Time was an obvious turning point, but even ‘The Drowners’ had a cello on it. Still Life had a SEVENTY piece orchestra. That’s insane.”

The second single, ‘The Wild Ones’ may have stalled at no. 19 in the charts, but it’s still my favourite Suede song. It’s also the best example of string orchestration on the album, acting as a subtle atmosphere that adds textures to the rises and falls.

Directly inspired by Jacques Brel ‘s ‘If You Go Away’, ‘The Wild Ones’ became an anthem for Suede, summing up their sombre mood as Bernard Butler departed the band in 1994, its spiralling chorus line “oh if you stay/we’ll fly through the skies/ suburban greys” was draped in a grandeur of longing, romance and loss, and is utterly spellbinding. It’s melody that is both reflective and imperious shoots across the sky.

Bernard Butler was absent for the orchestration of ‘Still Life’, he would leave the band mid way through the albums recording. A song that had been conceived initially by Butler during the final stages of recording their debut album. But the band weren’t sure how to arrange it yet. Scott Walker records again provided a clue, with Walker’s late-period arranger Brian Gascoigne drafted in to score the song, conducting the Sinfonia of London’s at Wembley’s CTS Studios. It’s certainly memorable, building from intimate, introspective beginnings Anderson’s baritone deepening against swelling strings into another epic soaring song. It’s a show-stopping finale that split opinion, but it’s an outstanding exclamation point to Dog Man Star particularly in its final portion where the orchestration stops to allow Anderson to deliver a haunting vocal as the entire arrangement sweeps back in. Some felt the arrangement was overwrought, “too much”. As Anderson explained, it’s the “story of someone waiting in vain for their lover to come home, sat by the window wondering who the approaching set of head lights belongs to. I suppose I cast myself as the housewife in this song and remember accessing a lot of latent pain in order to summon up the bleak imagery.”

Its grandiose production is a bit over the top even for some in the band and producer Ed Buller‘s tastes. “’Still Life’ is the only track that I really think fails, because it’s too over-the-top!” He told REPEAT fanzine in 2010. ” It was a nice idea, but it is so pretentious. Sometimes I listen to it and I think we pulled it off, but other times I listen to it and I think, “Ok, that was a step too far.” It’s difficult, because on Dog Man Star, a lot of it was experimental, I didn’t know what a lot of these songs sounded like, because on the first album, they could play them as a band, but on the second album, they really couldn’t play anything as a band. In fact, half of it was recorded with everybody separately, partly because of the difficult relationship Bernard was having with people at the time. So, it’s difficult and I can’t think of a Suede track that we really radically altered in production, no. I think they all pretty much turned out the way we intended.”

Without Butler’s involvement some argue it descends into gaudy camp, others like me love it. “Filmic but in a clichéd way,” says the band’s Mat Osman. “It was an ocean liner we couldn’t turn around,” he says now. “It’s rarely the things you thought were a good idea that people remember you for,” he concedes.

Releasing their first album in early ’90s with Too Pure, Stereolab were also fans of French pop. Led by songwriters Tim Gane, Mary Hansen and Lætitia Sadier they surfed the waxing and waning krautrock rhythms, Sadlier and Hansen’s melodies, playful organs and Gane’s ability to stretch a grab bag of kitsch samples. They were often joined by part time member Sean O’Hagen who adds choral string and keyboard parts influenced by his love of The Beach Boys‘ album Pet Sounds.

‘Ping Pong’ released in 1994 from the album Mars Audiac Quintet in particular takes influence from Gainsbourg, its breezy, cyclical sound, shot with the entwined lilting vocals of Sadier and Hansen, organs, gathering strings, horns and woodwind. It has a pleasingly slightly rough around the edges recording threaded with a hooky melody, jaunty guitar licks and deceptive lyrics about historical cycles, economics, economic cycles and wars. It’s a charming carousel of pop sound, replete with minimal classical arrangements that houses a weightier message.

Having produced songs like ‘Popscene ‘ and the choppy guitars, jabbing strings and London imagery of ‘For Tomorrow‘ perhaps the song that formed the template for Britpop on Blur’s 1993 album Modern Life is Rubbish. In April 1994, they would release Parklife, a massively acclaimed record, it contained songs that took their interest in grander arrangements up a notch with the influence of The Beatles and George Martin‘s work with the band at at Abbey Road. The Kinks and David Bowie are also more to the fore, most noticeably on, the music hall influenced ‘End of A Century’, the epic ‘This is a Low, and ‘To The End’ . This waltzing song with its bing-bong xylophones describes a couple unsuccessfully trying to overcome a bad patch in a relationship and features full orchestral accompaniment with a choric refrain in French by Sadier of Stereolab, it has a touch of Serge Gainsbourg echoing his duet ‘Bonnie and Clyde‘ with Brigitte Bardot about it. The song was produced by Stephen Hague, unlike the rest of the Parklife album, which was produced by Stephen Street.

Audrey Riley was called in to work on an arrangement for the track with her quartet following a lot of time spent recording in RAK studios. “I’d been working with Stephen (Hague) for a long time by then. So he would have sent me the track, (and the monitor mixes are probably upstairs somewhere), He would have sent me a CD of a monitor mix and I would have found a way to write an arrangement over it. Sometimes in the scores there’ll be extra markings or bits crossed out, if it’s been changed during the session, but there were no changes made here. We just recorded it as it was it. Then that would be that. I’d leave them with it and they’d mix it.”

“The only other thing I remember about the Blur session is Damon opening the door to the studio and saying ‘hello, you don’t remember me, do you?’ And I actually didn’t and then it turned out back in the 1980s, there was some idea that I might write songs and sing at one point and Geoff Travis was supporting me, but it didn’t work out. I was making a demo in a studio in Kings Cross and it turned out he had been working as the tape op that night. I remember thinking ‘I hope I was well behaved!?!’ But it was quite funny. You know, I think we both found that amusing.”

Part two to follow shortly.