A cornerstone of the British music press since its birth in 1986, the demise of Q magazine has brought an outpouring of hyperbole, grief and assertions about the death of the music industry (not just the music press).

It is particularly understandable coming from people losing their livelihoods and the realisation that the industry has failed to mitigate a changing climate, seeing the money drop out. The majority of music/culture writers are now working for very little, or no, cash. But that is a separate discussion to be had at another time.

Of course, much of the reasoning offered for this “death” is inherently ageist. In various forms, claims have been made that younger audiences “don’t read”, “don’t value music and art as WE did (the WE including everyone from the age of 30 upwards)” and that all music press “is just clickbait and regurgitated press releases anyway”. None of which is entirely true and is indicative of the head-in-the-sand approach to change of much of the music industry has had since the advent of downloading.

Younger audiences do read, they do value music and, often, do want great music journalism. They just don’t consume it in the way older generations do (or understand)!

Ironically, it is the rose-tinted looking back that made Q a success in the first place. While the music press in the 80s was looking forward, seeking out exciting new scenes, Q dared to be “uncool” looking at legacy acts and a middle-of-the-road that other titles scoffed at. As the CD buying age came in and older audiences began to replace their vinyl collection with shinny discs, Q was the bible they needed. Q thrived in the 80s and 90s by being the conservative voice of music, the antithesis of titles like the NME.

It might be hard to accept, but it is this grasping onto the past, that is Q’s undoing. Having maintained their focus on the obvious legacy acts (how many Oasis covers do you need?), done very little with design or format, and remained mass focus and mass market, they trod the path to obsoletion a little too readily. A lack of any real digital strategy was a nail in the coffin.

With the audience they service dwindling into old age, there was no creative or radical re-thinking of the content to mitigate this and attract a new audience.

In, hardly an official piece of research, but quite telling, we asked 10 people who posted about the sad demise if they had been buying Q. The result was only one person had bought it in the last five years, and most had not bought it in over a decade!

As the dust settles on the death of Q, these are some takeaways from the news:

Print is not ‘dead’, it’s just no longer mass market…

We haven’t needed to purchase print magazines to get our music content for a long time! The problem with the mainstream music press is that is has failed to accept this fact. Print publications are now specialist entities, collectable items not the mass market publications needed to get our music news, reviews and features.

But this doesn’t mean that smaller run, highly focused titles aren’t working. More on that in a moment.

… and music journalism is not dead either!

There is an abundance of incredible music journalists, creating exceptional content every day. The death of the classic print music press does highlight a problem, the industry has not worked out how to monetise the changing climate and as such, it is harder for writers to justify working in-depth for little or no money.

Older music journalists sometimes have an issue grasping the changing role of the music writer in 2020. The traditional voice of the critic has less value in an age where music is easily accessed online. Why do you need the opinion of anyone else when you can make up your own mind?

In its place comes a greater focus on curation, trusted voices sifting through the barrage of music to guide fans to the best sounds.

The reality, for those that wish to see it and engage, is that music “journalism” is diversifying online providing a more connected experience between artists and fans, the journalist is part of a much bigger mix. We connect directly via social media, listen to streaming, watch Youtube for music videos, interviews and short documentaries, listen to podcasts for a range of reasons. Tim Burgess’ excellent Twitter Listening Parties have created a new way for fans to engage directly with the music they love, going places and uncovering information no journalist has ever been!

Many traditional music journalists are struggling to find their place in this changing dynamic.

Print is art

Because printed material is not needed to share information on a mass scale in the digital age, it needs to have something special to be worthwhile. The quality of paper and often throw away design of classic music mags won’t cut it anymore. To get people to invest, print needs to be a collectable object in its own right, not just because of the writing but the design, photography and quality of print.

Alongside this, publishers need to look at smaller print runs, at a higher quality, and potentially with less frequency. For the right product, subscribers in print are willing to pay much higher cover prices than previously deemed acceptable.

Niche is king/queen/other

Mass appeal is not something that is achievable with print magazines any longer, so the real wins come from crafting a niche and becoming the stand-out voice for a chosen genre or scene.

While obviously not part of any discussions at Q regarding its future or editorial policies, from the outside looking in, it would appear that the above realities were not considered by the owners who continued to try and continue as usual. In this situation, its demise was inevitable.

The fact is that, at some point, as technology changes (improves?), audience needs alter and environmental concerns bring the consumption on unnecessary physical objects into question, print media might eventually die out altogether.

Is this the death of the medium in the way some people are predicting? Not likely, what these hyperbolic expressions of loss feed into is the fetishization of the object rather than the art, the packaging rather than the content.

And sure, it is hard to downplay the very real role physical objects have had in culture, the artwork, the liner notes, the tangible feeling of owning something and, not least, the simple way to monetise such objects. But the music, the art, will not cease to exist because the way it is delivered has changed. This is the same for music journalism.

What is working in music journalism right now?

Looking at the situation with Q, and even publications like the Guardian, it would be easy to assume that there is nothing happening in print music-wise. To the contrary, there are some vibrant titles doing great things in the media.

A bible for electronic music, Electronic Sound, has a solid model for what a print publication can be in 2020. Starting life as a digital-only magazine, the current print version with its exceptional design, quality niche writing and willingness to cover even the smallest new acts, has become a firm favourite for fans in that musical realm.

A bible for electronic music, Electronic Sound, has a solid model for what a print publication can be in 2020. Starting life as a digital-only magazine, the current print version with its exceptional design, quality niche writing and willingness to cover even the smallest new acts, has become a firm favourite for fans in that musical realm.

But it is their subscription package, that comes with a limited edition 7” vinyl single, or CD, tied into the cover content of that issue, that has set them apart. Releasing rare cuts from big names such as Devo, Jarvis Cocker, Hannah Peel, Amon Tobin and Factory records, these records have become collectable items in their own right. Doing very little online, they have found a new way to harness the object fetish for their own good.

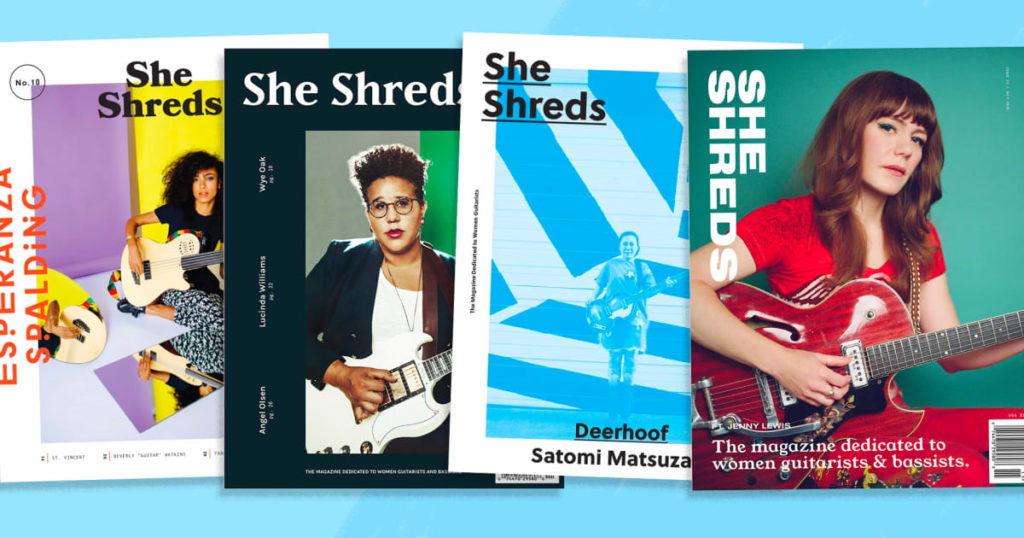

Although, it has now ceased to be a print magazine, She Shreds, is a perfect example of how finding interesting niches and covering underrepresented voices can pay off. Flipping the often sexist coverage of guitar players on its head, the magazine took female “shredders” seriously focusing not so much on their gender and appearance (certainly not writing with surprise that woman can play guitar) but more on their art, their playing and their creativity. It obviously struck a chord. The brand is now She Shreds Media working in a much wider capacity for the community they serve.

These are just some examples of how print is having some dynamic success. When we look online as well, platforms like Bandcamp Daily are taking curation to the next level, doing excellent deep dives into genres, labels and artists all tied into music for sale on their platform.

And of course, this only talks about the written word and doesn’t delve into how video, podcasts and mixes are doing great work in the field as well.

This is an off-the-top-of-our-heads thought on what is working and can work, with music press in this new age.

While the demise of Q is sad, it highlights how the whole industry has to adopt an “adapt or die” approach to the future.

The answers aren’t all there by any means, and this is a tough period for music journalism, but the outlook needn’t be 100% pessimistic. Instead of fantasising about the past, the industry needs to start looking at solutions for the future.

Q didn’t do this, and the reality is, it has cost them their existence.

James Thornhill runs new music marketing community Proxy Music, helping artists and record labels promote their music more effectively through learning, discussion and collaboration.