“Like a leper Messiah, when the kids had killed the man I had to break up the band.”

“Not only is it, not only is it the last show of the tour,” David Bowie announced breathlessly to an enraptured audience packed into Hammersmith Odeon on the 3rd July 1973, “but it’s the last show that we’ll ever do. Thank you.”

The young frenzied crowd, adorned in glitter and make-up, duly cheered on cue and banged on the barriers as they yelled up at the stage, but then, quickly, fell into a disbelieving hum of incredulous, shocked mutterings whilst exchanging confused and anxious glances; the last few words from their newly discovered alien messiah slowly washing over them. David Bowie had just killed Ziggy Stardust live on stage, as prophesied.

“It had only lasted, what little over a year?” Elbow’s frontman Guy Garvey supposes, “but it changed the world: David Bowie had changed the world… Everything was suddenly full of bright colour and kaleidoscope dreams.”

“When he came out with Ziggy Stardust, it was like an art installation. It was like, ‘Wow!’” Elton John says, before going on to readily admit that, “Without Ziggy Stardust, without Starman there would have been no Rocket Man.”

“It still sounds amazing,” he told the B.B.C. for their documentary, David Bowie and the Story of Ziggy Stardust.

“What I did with my Ziggy Stardust was package a totally credible, plastic rock and roll singer,” Bowie would say, looking back on his most famous, most inspirational alter-ego, “much better than the Monkees could ever fabricate. I mean, my plastic rock and roller was much more plastic than anybody’s.” He hadn’t known it at the time, but his “plastic rock and roller”, with those beautifully sculptured cheek bones, tight colourful androgynous costumes and highly sexualised gestures, would go on to change the world.

“He revolutionised the music business,” says the late Mick Rock in the documentary, whose photographs of Ziggy and The Spiders, both on stage and in the studio, are now iconic.

“It is one of my favourite LPs, still,” Joy Division bassist Peter Hook revealed to the B.B.C.

“It lit the blue touch paper of imagination,” according to Holly Johnson.

“The initial framework in ’71, when I first started thinking about Ziggy,” Bowie told MOJO magazine, “was as a musical-theatrical piece… it kind of became something other than that.”

Okay, so where were we? Oh yeah, Hunky Dory.

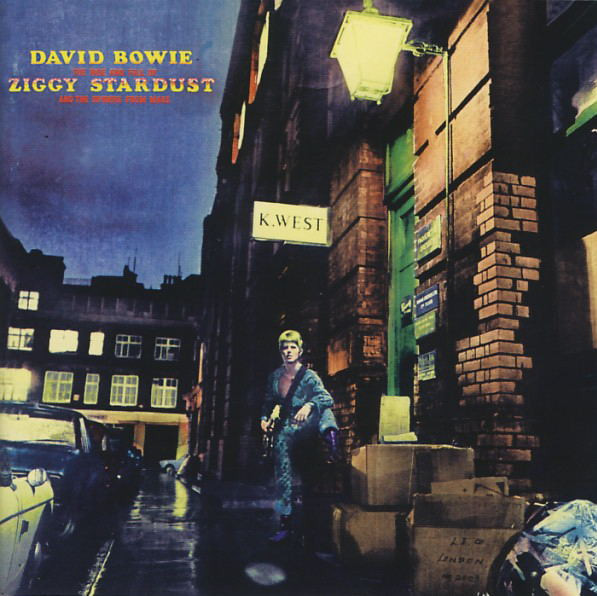

The album Hunky Dory had been released in November, 1971. Critically it had been well received, but, as its first single Changes was released, David Bowie had already moved on, and the songs that would go on to grace The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and The Spiders from Mars, had already been written. Bowie may have taken to the stage of The Old Grey Whistle Test to perform songs from Hunky Dory, but he was already looking and acting like Ziggy, and his band were, already, The Spiders.

As drummer Mick “Woody” Woodmansey revealed: “We only had a two week break between Hunky Dory and starting Ziggy. It was all kind of written and ready to roll,” he told the B.B.C.

Tucked away on the B-side of Hunky Dory though, after the tributes to Warhol and Dylan, was ‘Queen Bitch’, a song largely inspired by, and dedicated to, Lou Reed and The Velvet Underground. Unbeknownst to those listening to ‘Changes’ and ‘Life On Mars?’, or trying to work out the meaning, if any, behind ‘The Bewlay Brothers’, this song, lasting little over 3 minutes, was a sign of the mania that was about to land. It may have started with gentle strumming upon a 12-stringed guitar but it had ended in a rocking cacophony from the roaring, gold 1968 Gibson Les Paul Custom belonging to Mick Ronson.

“My Jeff Beck,” as Bowie always alluded. “I sort of hoodwinked him into working with me.”

Alongside ‘Queen Bitch’, Bowie had written another song. It was still without flesh, without a title, but it had the makings of what would become a chorus and the verses were almost complete, but the imagery it began to conjure, as Bowie cut up individual words and lines and then continually rearranged them, excited the singer and sparked his creative imagination. He continued to work on it whilst sitting cross-legged in the garden of Haddon Hall, that battered 12-string resting in his lap as he scribbled and toyed with a tune that would soon be called, ‘Moonage Daydream’.

Whilst ‘Queen Bitch’ made the final cut of Hunky Dory, ‘Moonage Daydream’ was put to one side, but the germs of an idea were beginning to take root in Bowie’s mind as he planned the next step forward: Arnold Corns.

So okay, The Arnold Corns project, designer Freddie Burretti miming along to a rather underwhelming, poorly disguised Bowie vocal, was again, thankfully, another flop – for who knows what the future of music would have looked like then? – the single not so much sinking without a trace, as rather crashing and exploding. But, as Bowie soon came to realise whilst staring at the still smouldering embers, if he was comfortable writing for a character, and more than happy for someone else to take the spotlight, whether it be Burretti or even Peter Noone, then why didn’t he just become that character himself? Why didn’t he take on a totally different persona for one final attempt at stardom? He could immerse himself in it and, more importantly, hide behind it? After all, he had already admitted to being “the actor”, and the songs, beginning with ‘Daydream’ and ‘Hang Onto Yourself’, had promise. And what if he cut off the flowing hippy locks, and then dyed what remained a dazzling shade of red? Experimented with all the wonders to be found inside his wife Angie’s make-up box and combine that look with the colourful if slightly effeminate outfits and tight catsuits that Freddie Burretti had so artfully designed?

As Bowie would later tell Michael Parkinson: “It was really the music and the showmanship of it all… I never thought that I could sing very well,” he revealed. “I used to kind of try on other people’s voices, if they appealed to me when I was a kid…” The voices of Anthony Newley with the showmanship of Little Richard?

“But when did you first start being camp?” Parkinson asked Bowie in the 2002 television interview.

“When I first put those clothes on funnily enough,” came the reply.

Trying to get his band – three rockers from the staunchly northern town of Hull – to wear the clothes however, would be a totally different story.

“Fuck off!” was, allegedly, Woody’s initial reaction.

“I’m not wearing that,” and Mick Ronson was adamant! “My mates’ll all be watching this.”

“To be honest, if Ronno had refused to wear the outfits?” Bowie later pondered for an Australian interview, “I probably would have dropped the idea… I wouldn’t have risked losing him, or the band.”

Thankfully, it was a decision he would never have to face, for after the first few shows it was becoming obvious that something was happening.

“All these girls were all over them,” a relaxed, witty Bowie revealed to Parkinson, “and suddenly the dressing room procedure was really different. ‘Right, who’s got the blush? Eh, Trevor! Have you finished with that mascara?’ It was a phenomenal thing.”

“I don’t think there ever was a concept to it,” producer Ken Scott once said in an interview with Guitar Player, “but somehow that became applied to the record. People find small things to put a story together.”

“There was a bit of a narrative,” Bowie explained to MOJO magazine, “a slight arc, and my intention was to fill it in more later,” to become the stage musical he had always wanted to create. “And I never got round to it because before I knew where I was we’d recorded the damn thing… I couldn’t afford to sit around for six months and write up a proper stage piece, I was too impatient.”

“He always described how he’d take bits and pieces from all over the place, from what he’d read, from what he’d seen,” Scott recalls. “Put them in a melting pot and they’d come out being him.”

The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and The Spiders from Mars begins slowly, innocuously; Mick “Woody” Woodmansey’s minimalistic drum resounding throughout the opening track, ‘Five Years’, like doomed Earth’s last desperate heartbeat, simply, continually beating out a rhythm to the dystopian scene of girls off their heads hitting tiny children and desperate cops kneeling to kiss the feet of priests:

“News guy wept when he told us, earth was really dying”, and Bowie’s voice had never sounded so emotionally raw, so full of forlorn yearning that was both heartfelt and urgent. He didn’t hold back, as Ken Scott remembers, watching from the production booth on the other side of the studio glass.

“By the end of it he was in tears, they were streaming down his face. Most of what you hear on the albums I co-produced with him, 90, 95% of the vocals were recorded in one take. It was amazing. He was amazing!”

“London was extremely poor,” and still very much carrying the scars of the war, Spandau Ballet’s Gary Kemp told the B.B.C. for the 2012 documentary, David Bowie and the Story of Ziggy Stardust. “In 1972 there were bomb sites still everywhere. There was a recession. There was a Cold War as well… He sang there’s only 5 years left of the Earth, and actually, in 1972, you did believe there was probably only 5 years.”

The relentless doom-ladened imagery that Bowie was describing so vividly, quickly resonated with a youth long bored of blue denim and beige patterned tank tops.

“I’m an alligator, I’m a mama-papa comin’ for you. I’m the space invader, I’ll be a rock’ n’ rollin’ bitch for you”.

Ziggy is first introduced during ‘Moonage Daydream’, along with ‘Hang Onto Yourself’, originally released by The Arnold Corns project. Here though, fully adorned and uninhibited, both songs reign brash and unashamed, out and proud, demanding to be taken seriously at this “second coming”: Hang Onto Yourself screaming impatiently that, “She’s a tongue twisting storm, she will come to the show tonight, Praying to the light machine”, warning that, even now, when all-consumed by fame, “The bitter comes out better on a stolen guitar, You’re the blessed, we’re the spiders from Mars”. The “She”, perhaps the character so softly described in the Bolan inspired song, ‘Lady Stardust’? The only still-devoted follower Ziggy has left, and ever loyal to the end, even as the now leper messiah is fallen upon and torn apart on the stage before her.

“You’re not alone,” she screams at Ziggy at the end of ‘Rock N’ Roll Suicide’. “Gimme your hands”!

When RCA first heard the album, although they liked it, even if they didn’t quite understand it, their immediate concern was that there wasn’t an obvious, all-important track that they could release as a promotional single. So the band went back to Trident Studios and Bowie once more picked up his trusty 12-string. After three quick rehearsals, Woody and Trevor looking at each other for clues as to where the verses ended and when the chorus came in, or even if there was a chorus, recording on ‘Starman’ got underway.

“So, you’ve only just got the bare bones of it in your head,’ Woody reveals, “and then, okay let’s go for it… You knew from experience that he didn’t like going more than three takes.”

“If it didn’t work after three takes,” Ken Scott confirms, “then he got bored.” It’s not working, on to the next thing.”

‘Starman’ quickly replaced Bowie’s cover of Chuck Berry’s, ‘Round And Round’, and was released by RCA on the 28th April, 1972. It was catchy. It was poppy. It was everything RCA wanted and exactly what Bowie needed. But, again, nothing happened… Until two months later. And that appearance on Top of the Pops.

“He’d like to come and meet us, But he thinks he’d blow our minds”.

“And no one had ever seen anything like that before,” Elton John has since said in several interviews, admitting for him the importance of David Bowie, and Ziggy Stardust. And, when he pointed down the lens of the camera, Gary Kemp was like so many future stars of pop and rock, so many writers and artists all watching the broadcast that night.

“I was sure he’d picked on me.”

More was to come though, Bowie casually draping an arm around another man’s shoulders in front of a now, no doubt gawping audience of millions! It looks so tame today, fifty years later, but back then. Nothing would ever be the same again!

‘Starman’ quickly climbed the charts to reach number 10, becoming Bowie’s first hit since ‘Space Oddity’; at last, gone was the label of, “One Hit Wonder”. Within days, the album had reached number 5 and everyone, even “fat, hairy truck drivers”, had that Ziggy haircut.

On the B-side of the single was ‘Suffragette City’, a song originally offered to, and rejected by, Mott the Hoople, one of Bowie’s favourite bands who were on the verge of splitting up. As singer Ian Hunter later explained to Far Out magazine: “I didn’t think it was good enough.” Not to be put off, legend has it that Bowie simply went to another office in London’s Regent Street and quickly wrote, ‘All The Young Dudes’, another glam rock anthem that would go on to become an even bigger hit than ‘Starman’. As the Hoople’s drummer, Dale Griffin, later told Rolling Stone magazine: “I’m thinking, ‘He wants to give us that?’ He must be crazy!”

“If it had been the other way round,” Hunter admits, “I wouldn’t have given it to him.” But Bowie was in the midst of a creative maelstrom, writing for and producing Mott The Hoople, Lou Reed and Iggy Pop. Just weeks later, Bowie would write another song especially for The Hoople, although the band turned ‘Drive In Saturday’ down, preferring instead to write songs for themselves.

The influences for The Rise and Fall… most notably include Jimi Hendrix, “played it left hand, but made it too far”, singer Vince Taylor, whose act Bowie was inspired by and whose story he heavily borrowed from – Taylor took too much L.S.D. whilst on stage one night and pronounced himself Jesus Christ, thereby committing professional suicide – and the Legendary Stardust Cowboy, from whom Ziggy acquired his surname. One other heavy influence though, was Bowie’s friend Marc Bolan, on whom the gorgeous ‘Lady Stardust’ was based.

“Laughed at his long black hair, his animal grace, The boy in the bright blue jeans, Jumped up on the stage, And lady stardust sang his songs, Of darkness and disgrace”.

Bolan was, at that time, widely regarded as the leader of this new music and arts movement coined Glam, but with Ziggy, Bowie was about to take it to a new stratosphere and Bolan could not keep up with his old friend. By the time he had caught up, Bowie had grown bored and jettisoned the make-up and extravagance of Ziggy Stardust, and all The Spiders, for a monotoned and cocaine ravaged thin white duke.

Ziggy was with us for little more than a year, but in that time music had been changed and the fabric of culture had been altered: here we are, fifty years later, still talking about Bowie, and writing yet more articles about The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and The Spiders from Mars, and the influence both exalted. The problem of linking artists who have been influenced by David Bowie ever since is, as music journalist Neil Norman admits, not where do you start, but where do you stop?

“Let’s start with New York Dolls,” he suggests on Sky Arts’ Discovering: David Bowie. “Let’s end with Lady Gaga,” who currently sports her own version of Bowie’s iconic lightning bolt, albeit smaller and all in blue. In between you have Punk and New Romanticism; the likes of The Clash and The Sex Pistols; Duran Duran and the aforementioned Spandau Ballet. Then there’s Oasis – listen to ‘Star’ and their song ‘Rock N’ Roll Star’ – and Blur; not to mention Suede, Pulp and Radiohead. Even Madonna! The list is endless, and continues to grow as new artists discover David Bowie and Ziggy Stardust.

Time Out magazine’s Kim Taylor Bennett agrees. “I don’t think you can underestimate how much of an impact the character of Ziggy Stardust has had on popular culture… he is the concept pop star!”

We’ll leave the importance of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars to the man himself:

“I’m very happy with Ziggy,” Bowie told Alan Yentob during the film Cracked Actor. “I think he was a very successful character. And I think I played him very well.”

The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and The Spiders from Mars was released on the 16th June, 1972.