This month, Spotify announced a new model that rewards artists on its platform who are popular and further marginalises emerging and independent label artists whose tracks only rack up 1000 in a year. So better news for artists who already have good numbers, but it’s a further blow to independent and emerging artists who are already struggling to tour, record, and carry on.

Bandcamp’s sale to Songtradr laying off half of its editorial staff in the process further threw into question a key platform for record and merch sales for artists. We have seen 67 venues closing this year alone in the UK. Everywhere you turn the grassroots and independent music that feeds the mainstream artists is under threat, struggling to exist, let alone thrive.

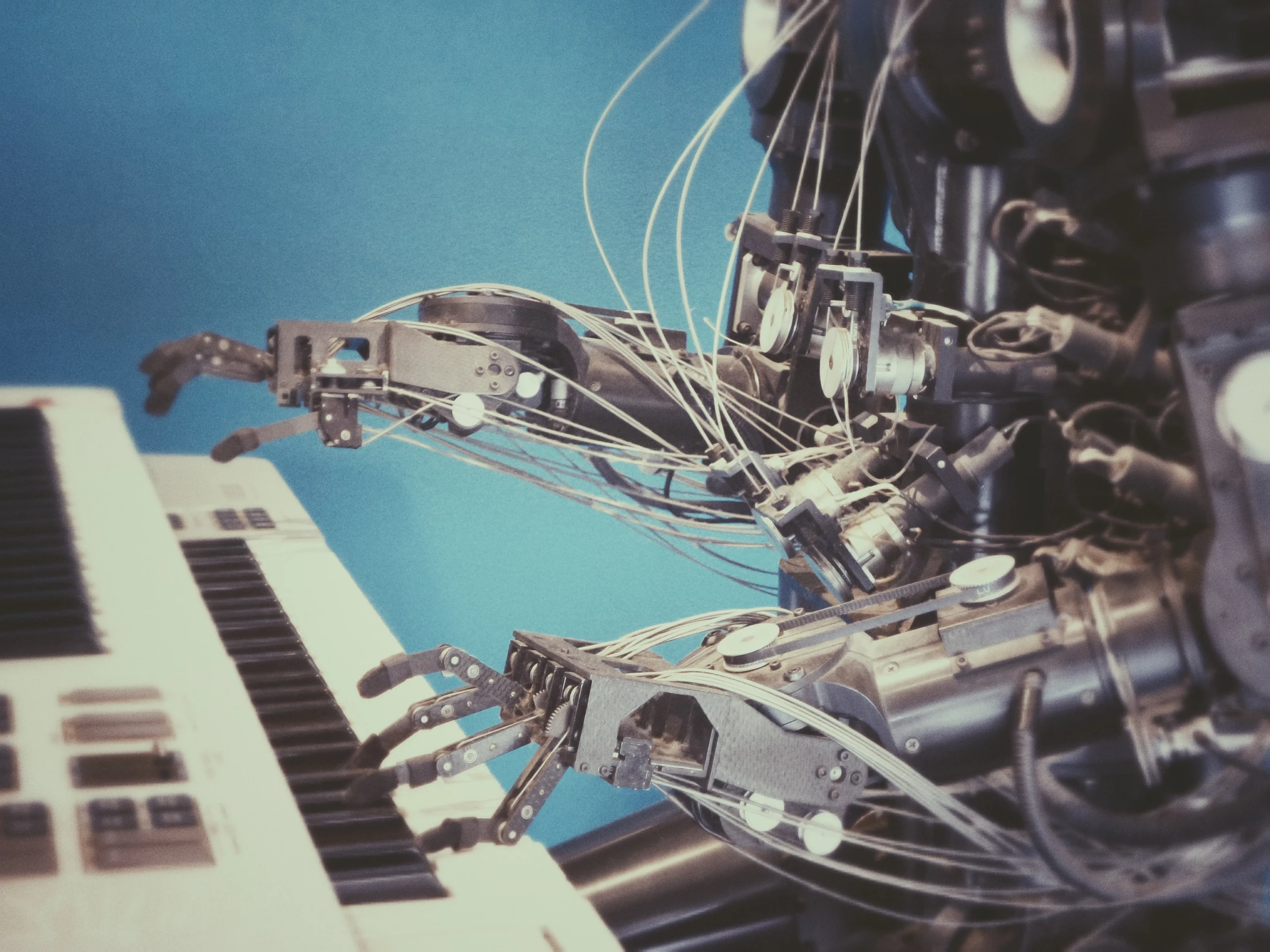

Now we turn to AI, a rapidly emerging and developing technology going far beyond just amusingly generic ChatGTP-generated lyrics (ask for a Coldplay-generated lyric and see if you can tell the difference between that and an actual Chris Martin lyric) or augmented AI-generated photography on your timeline. Deep fakes of images and songs created by AI models are being trained on copyright works without permission and generating new music that risks being indistinguishable from human-created music. As the technology gets more sophisticated it will be increasingly hard to tell which is human-created and which is completely created by AI. What’s real and what isn’t?

Examples from this year include a deep fake single ‘Heart on My Sleeve‘ that was billed as by Drake and The Weeknd taken down by their label and the band who made an album under the name AISIS with AI-augmented vocals that sound like Liam Gallagher‘s was described by the man himself as sounding “Mega“.

AI is rapidly changing the music industry, presenting both vast opportunities and new threats for independent artists and creatives. Some songwriters are using AI as part of their creative process embracing new technology to create songs more swiftly and dynamically.

Music has always evolved with technology and AI will be no different. Often it’s what an artist will feed into these technologies that produces the forward-thinking results. These new advances will potentially revolutionise production, songwriting, and how we consume music. But at what cost?

Copyright and likeness laws need revising and awareness of the copyright and ownership of an artist’s work need protecting. AI needs regulation because there is a real concern that platforms like Spotify and major labels will replace session musicians with AI-generated music, further squeezing the livelihoods of musicians. There’s a genuine fear that creatives could be erased from music and the arts altogether.

Sync and soundtrack opportunities are also areas where artists could be squeezed out by increasingly sophisticated AI technologies that can create music without human musicians. AI pop stars are already being signed to major label contracts, and when live shows feature computer-augmented music and visuals that don’t require the artists to perform in person such as ABBA‘s Voyage shows, is it really such a big leap?

Corporations always exploit new technology to make more profit. See Spotify’s latest move and the compromising of platforms like X now owned by Elon Musk, and Bandcamp being restructured shows that platforms targeting the bottom line over artists’ work will ultimately choose what’s best for their profit margins rather than investing in and promoting talent.

In this article, I will explore in-depth the way artists are harnessing AI technology to produce and promote new music and outline some of the very real threats and challenges that AI poses for music, culture, creatives, and the world.

STREAMING RECOMMENDATIONS

Social media and streaming applications already use AI. It’s already here, we already live with elements of it. Streaming services such as Spotify use AI to map their users’ listening habits. These algorithms break down a person’s tastes according to the tempo or mood of their favourite music, from this information they can build personalised recommendations for other songs.

General listening trends are also analyzed to customise playlists for users. Social media and internet sites are scoured for keywords about songs to build up profiles about how people are listening to them. For example, a song can be assigned a happiness rating, which can then be used to match it to a person who likes happy songs. It can also create playlists bulit on songs you like. These algorithms do manipulate listening figures, they also perpetuate streaming numbers of the most popular artists. They can also create passive listeners. Artists and campaigners, also argue that if Spotify is curating music playlists and playing songs on shuffle is this a form of broadcasting, and should it recompense artists in the same way PRS does?

As AI develops new applications will emerge allowing the user to ask for music by mood or to even create their songs by prompt, so if I want a chill track inspired by ‘The Orb’ with the vocals of Liz Fraser” it may be possible to call upon them in the future. Google have already launched an Application that can call up sounds based on mood on command so the next step may be coming.

Streaming platforms already marginalise artists. The Broken Record campaign has long argued Spotify needs a fairer royalties settlement for artists. Spotify’s new announcement that it would further reward bigger artists and defund artists who get less than 1000 streams annually on its platform has caused more anger and further squeezes struggling artists and labels. Competitions expert Amelia Fletcher – of Heavenly and Swansea Sound – pointed out that Spotify is so dominant in the digital music market that most grassroots artists need their tracks on the platform and will be forced to accept these new unfavourable terms. “Not only is it intrinsically unfair,” she said of the proposed new system, “but it is also anticompetitive and seriously risks constituting an abuse of dominance under UK and EU competition law.”

SONGWRITING

Emerging AI applications and tools are springing up to help make music production and song-writing to become swifter, giving users the ability to create tracks from scratch using prompts, by augmenting the songwriting and production process, creating endless possibilities for the artist and listener. Fully generative apps train AI models on extensive databases of existing copyrighted music. This enables them to learn musical structures, harmonies, melodies, rhythms, dynamics, timbres, and form, and generate new content that stylistically matches the material in the database.

AI is capable of helping with lyrics too: Audoir is an application for generating song lyrics and prose, Jarvis helps break writer’s block, ChatGTP can generate entire lyrics for songs that haven’t been played yet. Is this an extension of David Bowie’s cut-up lyrics technique? Or something more “manufactured” and “exploitive”?

“With all the love and respect in the world, the track is bulls*** and a grotesque mockery of what it is to be human,” responded Nick Cave on his blog, when a fan sent him song lyrics “in the style of Nick Cave”, generated by ChatGPT.

Crispin Hunt former front man of the Longpigs, and former Ivors Academy chair tweeted a quote: “It’s odd how often technicians tend to misunderstand the creative process assuming that imitation ( a necessary part of creation) is the same as appropriation. It’s not. Imitation breeds invention, appropriation never. AI creation is ipso facto derivative not transformative. It is a collage of the past disguised as the future.”

Boomy is an AI music generator that boasts it has created more than 16 million original songs since its launch in 2019. Using a simple prompt you can create a composition that sounds like “deep house with witch house vocals” for example. This year, Spotify purged thousands of these tracks from its catalogue following accusations that bots were being used to artificially inflate the streaming numbers and thus the revenues of these songs. They’ve since allowed the company to re-upload the tracks.

However, the growth in these applications throws up many questions and legal arguments around copyright and whose work they are appropriating. The algorithms powering these apps can infringe upon existing copyrights. These AI applications are created and modeled using the data of existing music to create new songs, which is certain to create similarities between the music in the data set and the generated content. But shouldn’t the artist be asked for their permission?

Streaming services like Spotify, Apple, and Amazon Music are are encouraged to develop their own AI music-generation technology. Spotify, pays 70% of the revenue of each stream to the artist who created and wrote it. If the company could generate that music with its own algorithms, it could cut human artists and musicians out of the equation altogether.

“The largest implication for AI and music is that creation is going to get easier,” Jessica Powell, CEO of San Francisco’s Audioshake told the FT.

Audioshake uses a form of AI technology called “audio source separation” to identify the components of a piece of music and strip them into individual stems. Audioshake can then be used to remix songs or turn them into instrumentals for sync opportunities or music libraries that license music for use in television, fitness, films, adverts and games. It enables a songwriter to experiment with different ideas, allowing users to select whether a female or male vocalist might work best in a piece of music. Among its clients is a futuristic Augmented Reality APP called Minibeats that allows people to create sounds through facial recognition and physical movements, a songwriting version of the Wii if you will.

Kat Five from the London electronic band Feral Five told me: “I’ve experimented with things like an AI bass player or a version of that, which is designed to be used as a production tool. And experimented with some of the generative AI like the Google one and the stable audio one. So I was trying things out.”

As part of this year’s Sŵn festival, the University of South Wales held a demonstration of DAACI, a new AI production tool that creates music to spec within seconds, with a form of remixing. One of our contributors and Boomtown promoter and DJ Kaptin Barrett reported on the demonstration on his blog:

“Now I know next to nothing about music theory or production so there are definitely things I missed on how it works exactly, but the demonstration was impressive, as the team took an original track by Welsh singer Kate Westall whose music I was introduced to through her Hospital Records collaborations with Fred V & Grafix, and using the tool, created 3 new remixes.”

“First they played the track in question, a lovely, folky, ukulele-led song called ‘Words’ into the system, then 10 seconds later DAACI had come up with a passable pop version, with a bit of a Glass Animals vibe. Producer Tom Manning then tweaked it a little, adding more chords and rhythm. Whilst I couldn’t work out exactly how he was doing that, it looked a hell of a lot easier than any recording package I’ve seen previously. What came out was admittedly pretty middle-of-the-road Spotify pop fodder but the time frame was impressive to rework the track like that.”

Kat Five says that there is a danger that some AI tools make very generic compositions: “I think one of the problems with AI very generally, is that, because it trains on math data there’s a certain kind of smoothing out and a certain blandness and blandification and a boringification, potentially occurring. Which means it’s also dangerous in terms of new genres, because, how do new genres spring up? They spring up when people are pushing the boundaries, and smashing things together, that aren’t normally smashed together. “

A project from Eryk Salvaggio under the title The Organizing Committee creates electronic pop music with AI technology they say their work “is an attempt to bring artificial intelligence into underground pop music, and do it in a reflexive way.”

Salvaggio says “Sometimes that means an AI is generating lyrics — usually produced by a customized GPT-2/GPT-3 model trained on cybernetics, situationist, and feminist texts. Sometimes it means building tracks around samples produced by generative means, be it from data produced by the GPS drift of a tracked eagle, or output from the OpenAI’s Jukebox. In all cases, the songs aim to push ideologies of computation “beyond the binary.”

MIXING AND MASTERING

Machine learning apps help musicians and producers with mixing and mastering: whether that’s balancing instruments or cleaning up the audio in a song. These are tools for those without the experience, skills, and time to pull off professional tracks that sound like they were recorded and mixed in a studio.

Over the past decade, AI’s use in music production has changed how music is mixed and mastered. The conversation points to “AI-driven apps like Landr, Cryo Mix, and iZotope’s Neutron can automatically analyze tracks, balance audio levels, and remove noise.”

These technologies can help speed up and streamline production, giving more time to musicians and producers to focus on the production choices and creative aspects of their work and leave some of the technical and time-consuming aspects to AI. Paul McCartney used AI to clean up hiss on a John Lennon vocal tape to help him complete the much-vaunted final song by The Beatles song ‘Now and Then‘ , something they couldn’t achieve in the 1990s.

It has also led people to ask if other demos from long gone artists will be digitally recovered using AI, it feeds potentially into a never satisfied nostalgia industry, always looking for a way to montezise the work of legendary deceased musicians. See the catalogues of Tupac and Hendrix that have been mined to exhaustion.

While these apps will take work away from professional mixers and producers, they also allow them to complete smaller jobs in less time, such as mixing or mastering for a local band, leaving more time for better paid commissions that require more work. Like Garageband before it these apps could democratise the production process, allowing DIY musicians to produce more professional-sounding work from their bedroom without involving an audio engineer they can’t afford. Although these also cause disquiet for critics and those working in the sector, increasingly putting producers and mixers out of work, also potentially causing a two tier system for those who can’t afford to use this technology.

The artist Kat Five says: “I think we need to be educating ourselves and also getting helped to, to educate ourselves. One of the things I worry about is, as much as I think AI can provide great new opportunities and tools and whole new ways of music creation, the last thing we need is like a digital divide, you know, where people who don’t have the time or the access and feel very left behind.”

INSTRUMENTAL AND VOCAL REPRODUCTION

This isn’t Sci-Fi, musicians and producers can already use AI to realistically reproduce the sound of any instrument or voice you can imagine. The drawback is that this technology can rob instrumentalists and session musicians of the opportunity to play on a recording meaning a loss of work for musicians. With “tone transfer” algorithms via apps like Mawf, musicians can transform the sound of one instrument into another one.

Thai musician and engineer Yaboi Hanoi’s song ‘Enter Demons & Gods,’ which won the third international AI Song Contest in 2022, used a reproduction of a traditional Thai woodwind instrument – the pi nai as part of its composition.

A variant of this technology is the Vocaloid voice synthesis software, which allows users to produce convincingly human vocal tracks with swappable voices. But there are issues this throws up around cultural appropriation, racial stereotyping and copyright.

In 2021, Capitol Music Group signed an “AI rapper” that was given the avatar of a Black male cyborg, but which was actually the work of Factory New a team of non-Black software engineers. The New York Times reported “ FN Meka, whose look, outlaw persona and suggestive lyrics were inspired by real-life music stars like Travis Scott, 6ix9ine, and Lil Pump, amid criticism that the project was profiting off stereotypes. The backlash was swift, with the record label roundly excoriated for blatant cultural appropriation.”

“There are humans behind technology,” Sinead Bovell, the founder of WAYE, which educates young people about technology told the New York Times “When we disconnect the two, that’s where we could potentially risk harm for different marginalized groups.

“What concerns me about the world of avatars, is we have a situation where people can create and profit off the ethnic group an avatar represents without being a part of that ethnic group.”

AI musical cultural appropriation is easier to become caught up in, than you might think say the Conversation. “With the extraordinary amount of songs and samples that comprise the AI data sets, there’s a higher chance that a user may accidentally upload a newly generated track that pulls from a culture that isn’t their own, or cribs from an artist in a way that too closely mimics the original.”

Vocal cloning is another area where AI is making an impact. Computer models are trained on recordings of people’s voices to create a near copy that can be made to say or sing whatever its user chooses. Often, this will be a funny juxtaposition in which an such as Kurt Cobain AI singing a Gorillaz track (see below). Other artists are using them to create and disseminate their voice. Grimes aka Claire Boucher, also unveiled an AI software, Elf.Tech, which allows other people to sing through her voice, and encouraged musicians to release songs using it, provided that they split royalties with her.

Kat Five explains how she used bespoke technology to augment her voice on Feral Five recordings “So for our album that was out early this year, we collaborated with some technologists from Berlin called Birds on Mars. They created a bespoke AI for us based around my voice, which we then play a bit like a synthesized AI can. It’s not a public-facing APP. That was great to experiment with it, to get to use it in a very creative way to get an alternative voice if you like, as a speaker of truth on our album, which is about truth and trust. “

Holly+ is an application created by the artist and commentator Holly Herndon. Time says: “Working with technologists she created a vocal deepfake of herself in 2021 by extensively training a neural network on her voice. Now, any amateur musician can use Holly+ to transform their pedestrian voice into hers, perfectly tuned and ethereal.”

The idea of handing over your voice for public manipulation might sound dystopic, by surrendering your voice to computers are you relinquishing control? But Herndon says she’s created Holly+ to spur her fellow artists to “gain agency over their careers and creative autonomy in the midst of a technological revolution” she feels will dramatically “shift how we make and process art.” The world is barreling toward an era of “infinite media,” where artists and fans can create their own songs. Herndon told Time “where anyone can rap as Drake or paint as van Gogh. She argued this makes it all the more crucial to give artists the power to determine what happens with their likenesses and voices.” She has also set up her own model for selling these re-works and spreading the royalties between herself and the artists reworking her vocals.

Kat Five is inspired by Herndon’s work “I love the fact that she’s not only been experimenting in this arena for years and creating her own AI. But she’s trying to democratize it with her Holly+ AI that anyone can use and use to create a track. Then if they want to submit it should consider releasing it and sharing the profit. That’s just such, you know, forward-thinking stuff.“

Bad actors misusing applications of this type are popping up outside of the musical realm. In politics, we have also seen deep fake videos of Trump and Biden plus shadowy tech figures pushing extreme positions through fake visuals. AI voice swapping has been used by criminals and fraudsters to scam people out of money.

Deep fake videos are being used by fans to put their spin on their favourite artist’s tracks too. Artists are also using deepfake imagery and sound, some misusing, others playing with notions of reality such as Kendrick Lamar.

KILL, THE ICON! created an AI music video for our single Deathwish earlier this year.

“Most people were overwhelmingly positive that we were able to use AI as a means of protest. “ Explains Kill, The Ion!’s Nishant “Our video was deliberately different from a typical “deepfake” – we wanted to subvert the concept of a deepfake, by putting their own words in their own mouths, but using my voice.

I learned a lot from the process, which was painstaking and arduous. It took weeks of 3am nights using AI software like Midjourney as well as a few different lipsync apps.

I explored it from an ethical point of view. There is a question about to what extent AI is trained on artists’ existing work, without explicit consent. I reasoned that this will be up in the air until legal test cases take place, and history tells us that early explorations of new technology are a sound basis for discussions around legal and ethical frameworks to be built.”

Following on from the AI-generated Weeknd and Drake track earlier this year, music business worldwide reported last month that Bad Bunny has “expressed his fury over an AI-generated track that artificially replicates the sound of his vocals, as well as those of Justin Bieber and Daddy Yankee.

The purported maker of that track, which has over 22 million plays on TikTok, calls themselves FlowGPT.

In a message responding to Bad Bunny published on TikTok, FlowGPT offered to let the artist re-record the AI-generated track “for free with all rights… but don’t forget to credit FlowGPT”.

There are also AI pop stars being signed too, with major labels signing them up and promoting them. A new one called Anna Indiana released a single this week called ‘Betrayed by This Town’. With heavily synthesized, auto tuned vocals and generic music: it claims to be the first ever completely “AI generated pop star” which is untrue as AI is trained on the work and likeness of artists and musicians. A disclaimer under the video on Twitter read.

“The vocals in this video are provided by Synthesizer V Natalie. However, it is against Synthesizer V TOS to utilize the voice database using a name that is not that of the database. Claiming that “Anna” is a singer while using Natalie is misleading, and violates this rule.”

“Synthesizer V AI Natalie (native language: English) is a feminine English voice database with a voice that presents a soft and clear upper range as well as rich and expressive vocals on lower notes.” The resulting song sounds very soulless, musically formulaic and creepy, a bit like a character from a Black Mirror episode. It brought a critical response from Music Venue Trust head Mark Davyd on Facebook:

“There’s a clip doing the rounds of the first completely AI generated singer/songwriter which has chosen the name Anna Indiana. The entire effort, the instruments, the voice, the image, the song, lyrics, melody, chords, everything, is AI generated.

It is, objectively, absolutely sodding dreadful. It has no redeeming qualities whatsoever. Every note of it sounds like it was crushed out the back of a waste disposal unit, stomped on to ensure it was lifeless, then inserted into a special machine that removes any accidentally remaining trace of empathy, grace, imagination or soul.”

BACKROOM PROCESSES

We all know independent artists often have to be everything these days, tour managers, social media managers, and press release writers, Kat Five believes AI will help with a lot of “backroom processes” in music.

“I think a lot of people are using it for press releases and there’s that horrible word ‘content’, artists are being driven by the need to make lots of content. It can be helpful if you’re writing press releases, I know someone running a festival who was using it to help with their their PR work. So it could help free us up with backroom processes and you know, the more help we can get with that the better.”

That is a potential positive of AI , but on the other hand, it could lead to big job losses in areas of PR, journalism, and the media. With entire sites created with AI and automated news aggregators, rather than actual journalists to update the news.

According to PwC: “Artificial Intelligence (AI) and related technologies are projected to create as many jobs as they displace in the UK over the next 20 years, according to their analysis.” They say around 7 million existing jobs could be displaced, this will disproportionately impact sectors with physical creatures and manufacturing. While the health and social sectors will see job growth.

This is a challenge for creatives and the media sector but no doubt it will also bring further opportunities to re-train, with the role of “prompt engineer” will be in demand. Kat Five agrees she says it is “people who can prompt AI in creative ways. It is really like the Wild West the whole thing. We really have to sort of make our mark and then carve a way through it that works.”

ARTIST RIGHTS

AI models are currently trained on the music and vocals of existing music. The hard work of artists are being cannibalised by AI applications to create AI-augmented and created songs, without their permission. We urgently need copyright and regulatory laws to protect artists, who should be asked for permission for their work to be used.

As these AI models and tools become more sophisticated and are programmed using artists’ work that already exists, strengthened regulation on AI and copyright laws will become even more crucial for artists. In visual art there is an ability to opt out of having your work used to form the basis of training for visual AI apps, there’s a website where artists can upload images and find out whether their work has been used to train tools in AI imagery. Maybe the same will be true of music in future years? Where you can upload a track and see all of the tracks created in its likeness of sound, finding their watermarks and seeking royalty payments or to opt out of this.

The Council of Music Makers of which the Ivors academy is a founding member, recently released a letter that can be sent to artists publishers, explaining why it’s important to send a letter of non-consent for the use of their music to train AI models.

“It is important for you to be aware of your rights and to take steps to protect your work. One way to do this is to send a letter of non-consent to your publisher. This letter states that you do not consent to your music being used to train AI models or to create derivative works and has been created by the Council of Music Makers of which the Ivors Academy is a founding member.”

American lawyer Craig Averill told NPR “The author has to be a human as the law stands. It can’t be completely computer-generated.”

But Averill explains questions remain about the amount of human intervention needed to make AI-generated musical works copyrightable. Asking the pertinent question if the face of the work isn’t a human, then who’s the copyright holder? “If you come up with a composition and then you have an animated character that’s front-facing for it, and you don’t have to really pay that entity any royalties, what does that look like?”

“Artists stand on the shoulders of giants. AI eats said giants.” said arts advocate Neil Turkewitz on Twitter “Let’s be really clear here. The AI companies that don’t want to negotiate with artists over usage terms for training AI have sought to portray this as a fight over technology. As the past resisting the future. It is not. “

A strand of its champions argue that critics of AI are scaremongering luddites, but Turkewitz argues that argument is too simplistic: “Artists are contesting exploitation, not technology. Anyone that characterizes this as pro AI v anti AI artists is both failing to understand reality, & being a useful tool for exploitative AI companies. Any journalist that portrays this as the old guard resisting change is contributing to exploitation. So please don’t do it Artists & other creators should be paid for use of their works.

“Ascribing agency to [AI] diminishes the complexity of human creativity, robs artists of credit (and in many cases compensation), and transfers accountability from the organizations creating [AI] , and the practices of these organizations which should be scrutinized, to the [AI generators] themselves” argued Crispin Hunt on Twitter of vaunted AI created music.

The Human artistry campaign argues “there are fundamental elements of our culture that are uniquely human. Only humans are capable of communicating the endless intricacies, nuances, and complications of the human condition through art – whether it be music, performance, writing, or any other form of creativity.”

Developments in artificial intelligence are exciting and could advance the world farther than we ever thought possible. But AI can never replace human expression and artistry.”

As new technologies emerge and enter such central aspects of our existence, it must be done responsibly and with respect for the irreplaceable artists, performers, and creatives who have shaped our history and will chart the next chapters of human experience.”

Jessica Powell argues that fears of an AI takeover in music are overblown. Human talent will continue to be central even as the work itself becomes ever more technologically driven. “What is the story behind a song?” she says. “Who is performing it? What is their larger social or cultural context? How are they interacting with their fans? Taylor Swift is far more than a Taylor Swift song.”

REGULATION

The UK government has said it will refrain from regulating the British artificial intelligence sector, even as the administrations in the EU, US and China push forward with new measures. The UK’s first minister for AI and intellectual property, Viscount Jonathan Camrose, said at a Financial Times conference that there would be no UK law on AI “in the short term” because the government was concerned that heavy-handed regulation could curb industry growth.

Oxford’s Institute for Ethics in AI senior research Elizabeth Renieris told BBC News, she worried more about immediate risks: “Advancements in AI will magnify the scale of automated decision-making that is biased, discriminatory, exclusionary or otherwise unfair while also being inscrutable and incontestable,” she said. They would “drive an exponential increase in the volume and spread of misinformation, thereby fracturing reality and eroding the public trust, and drive further inequality, particularly for those who remain on the wrong side of the digital divide”.

Ms Renieris said. Many are trained on human-created content, text, art and music they can then imitate – and their creators “have effectively transferred tremendous wealth and power from the public sphere to a small handful of private entities”.

The EU has led the field, with its legislation on AI regulation expected to come into force before the end of this year. The UK government said it did not intend to legislate the domestic AI sector in the immediate future. “As we have done throughout, we will develop our approach in close consultation with industry and civil society, maintaining a pro-innovation approach,” it said. In a white paper published in March, officials put forward a proposal “to split responsibility for AI supervision between exiting bodies — including those for human rights, health and safety, and competition — instead of establishing a bespoke regulator.”

In contrast Labour have suggested they would look into a toughing regulations were it to enter office in the next twelve months.

Labour leader Kier Starmer was reported to have said “We are nowhere near where we need to be on the question of regulation.” Starmer said he was struck by the pace of development in AI, he said it could have a transformative impact, helping the NHS diagnose illnesses and enabling public services reform. But he said the technology carried serious risks, including misinformation and widespread job losses. The impact on jobs would require a renewed focus on skills and training, he said.

Labour has been working on a tech policy paper for months, which is being led by Shadow Digital Secretary Lucy Powell.

Kat Five thinks the dangers are great to artists getting rememorated, recognised and further demonetized by AI. “I think there is a real danger that artists and musicians will be at the bottom of the pile when it comes to getting rewarded for their work, or even getting work at all.

“I think it’s really necessary that we find ways of raising our voice in this environment and mechanisms of holding big tech companies to account because also they themselves say they want to be held to account,” says Kat Five “They are also pushing for some kind of oversight and even regulation, because I think one of the problems of music is that often people see music in isolation. And actually, the things that musicians are facing are the same thing that writers are facing and artists are. What we’re seeing is some sort of Pan creators rights organizations emerging. But we need a lot more transparency, I think we need generated AI generated music to be clearly labeled, and again, watermarked.”

Following the announcement that the Department For Culture, Media & Sport has convened a roundtable on AI and the creative industries. The Council Of Music Makers wrote a open letter:

“We greatly welcome the acknowledgement from Culture Secretary Lucy Frazer that “creatives rightly have concerns – and proposals – about how their work is used by artificial intelligence now and in the future”, as well as her commitment to listen to and consider those concerns and proposals. But to do this, it is important that the voices of music-makers themselves are a key part of the conversation. “

We are hugely concerned that the government is forming a roundtable which only gives one single seat to a representative of all creatives across all media (including film, theatre, literature and music), but has three seats for executives from major record companies. This is profoundly unbalanced and tone-deaf.

It is crucial to understand that when corporate rightsholders make decisions about digital polices and digital business models, they do so without consulting the music-making community. These decisions are made unilaterally in secret and are rarely even communicated to music-makers and their teams.”

The last 25 years have also demonstrated that – when making these decisions – corporate rightsholders always prioritise the interests of their shareholders. It is true that sometimes the interests of those shareholders and music-makers are aligned, but sometimes they are diametrically opposed.

“With streaming, the corporate rightsholders worked in secret with the streaming services to develop a business model that served the interests of their shareholders. Music-makers had to employ considerable detective skills to figure out how this model worked and then undertake significant lobbying efforts to instigate a discussion about the issues with the model.

However, the corporate rightsholders are now making changes to the streaming model, while also developing brand new business models with AI companies. Again, the music-maker community is not being consulted, with decisions being taken unilaterally by record labels and the technology companies. Deals are being done in secret, with decisions only communicated through press releases.

“Of course, both corporate rightsholders and music-makers believe that AI companies must respect copyright and other creator rights – on that we are aligned. But corporate rightsholders cannot and do not speak for music-makers, and it cannot be assumed they are making decisions in the interest of music-makers.”

“We urge record labels and the technology companies to actively engage with music-makers on AI. And we call on government to ensure that human creators are at the centre of its valuable work to ensure that the opportunities of AI are achieved in a way that benefits everyone, and especially the people who create the music we all love and which makes a significant contribution to the UK’s public purse. “

Neil Turkewitz argues artists “shouldn’t be indentured servants forced to cultivate the tools of their own demise. This isn’t about technology—it’s about human conduct. Let’s be the best version of ourselves.”

CONCLUSION

To return to the question I posed in the title, the answer is this fast advancing AI technology is both a vast opportunity for artists and creatives and also a threat to their work and livelihoods. When asked, Paul McCartney said that AI represents a “scary” but “exciting” future for music, which sums up both the dystopic trepidation, excitement and fear about this new technology.

Music has always evolved with technology but the AI trend in music, also throws up huge questions around copyright, regulation, and about whether AI can ever replicate the work of artists and musicians or is it simply appropriating them? Productional advances in AI both give artists new tools to explore but also throw up existential questions about the nature of art and humanity.

A big proponent of this technology, Grimes, argued on a podcast recently that AI is at the point where it will develop beyond our own thinking “I feel like we’re in the end of human art, Once there’s actually AGI [Artificial General Intelligence – the point at which AI surpasses human intelligence in most tasks], they’re gonna be so much better at making art than us.”

Champions of AI appear to be in love with the process and the democratizing idea that AI can make anyone an artist, and to an extent there’s some merit in that, but the idea that machines can totally erase and demonetize creatives is both troubling and currently untrue, when the very technology used to create this AI music relies on the work of artists to form its modelling, and the likeness, sound and brand of the artists in the case of deepfakes. The parts of the music that aren’t perfect are often what excite and pushes it forward, human beings are messy and often what shines through are the moments inspired by emotion and soul, that AI can’t replicate. As Mark Davys says “The excited rush to use AI to replace human creative activity needs a serious rethink. Maybe robots could, I dunno, do practical and repetitive tasks that we don’t want or need to?“

Also in this era of social media, STANS want to get even closer to their favourite artists, they want a closer connection not blank automation. There’s been a rise in vinyl sales and gig tickets are increasingly in price, AI artists can’t provide that human connection that we crave, that expression that closeness, the queuing before a show or a signing, the reading and dissecting of lyrics and how they relate to actual events and human experiences.

Artist Conal Kelly, told the Independent “I do worry AI will dilute people’s music tastes to the extent that it’s either impossible to tell what’s been written by a machine vs human, or the public will prefer AI songwriting. That’s a dangerous place for the world to be. For an artist, anyway.”

Iranian electronica composer Ash Koosha argued in the Independent “In music, the person is the product. From Billie Eilish to Nick Cave… we care about their life story. Even if it’s the year 2200, we’ll still be looking for that person that has a story to tell. I wouldn’t bet on [music] labels being able to use AI to find the next The Weeknd. I believe in humans more than many marketing or tech companies would like to.”

Kaptin Barrett says: “There’s no escaping AI so I’d urge creatives to embrace it to whichever degree they find it useful. The last thing I’d like to see is it being put solely in the hands of those who wish to erase creatives from the process entirely. The risks are definitely there, especially for things like soundtracks and other sync opportunities which can serve as a lifeline for musicians when revenue from sales themselves appears to be ever decreasing.”

He explains that as we are at the formative stages of AI in music, and much of what it produces is generic copy currently, but what maybe the exciting part is when artists learn how to break it apart, misappropriate it like the best remixes and mashups can. He continues, “The best that can happen is it pushes, and facilitates artists to become even more creative in their work. There was another Hospital recording artist at the demonstration, Landslide. He made a good point, that the moment AI becomes really exciting is when people learn how to properly misappropriate it. I’m sure that’s already happening and I look forward to seeing how that plays out.”

We are already drowning in music with thousands of tracks added to platforms every month, the risk with AI is that we will see another deluge and the quality could be watered down. In future years we may be often asking ourselves, whether a song involves a human or not and does that matter? Maybe rather than Parental Advisory sticker on records in future should have a sticker labelled “created by AI?” YouTube are already flagging AI music.

As augmented reality and the metaverse potentially becomes a place where we interact and intersect with the world, is it really much of leap to enjoy the work of a AI avatar? Not for some younger people it seems, some people won’t care if the music sounds good. Although the market as always decides, when a AI generated Beatles inspired song called ‘Daddy’s Car’ created by patterning of their entire catalogue was released in 2016, it didn’t take off. “People will always want original music and the likes of Milli Vanilli and Ashlee Simpson are living proof as to how audiences feel about authenticity.” Nishant points out.

Whilst questioning is always valid, there is a danger we enter a black and white “real music” argument which has constantly pushed back against advances in music, from the cries of “Judas!” at Dylan when he plugged in an electric guitar in the 60s, the snobbish attitude adopted to synth pop bands like Depeche Mode by the music press in the 80s, right up to the current day when artists like Billy No Mates who got criticised for using a backing track on stage at Glastonbury, which is crazy when many pop stars do the same. This kind of snobbery is the other extreme and no doubt there will be those that will never accept AI enhanced or generated music on principle but isn’t it the case that technology is often used in music as a way of expressing? Not everyone has to use guitar, bass and drums. That’s how art evolves, and artists have constantly pushed the boundaries in their quest for expression, some AI technologies can clearly aid and compliment creativity and songwriting.

By the same token soul and humanity is an essential essence of art and expression, how we see the world and how we navigate it and relate to each other as human beings. That’s why the potential erasure of humans from music and creativity is so scary and should be opposed as another way for corporates to erase the presence of artists and musicians in the search for more profit. The topic is both fascinating complex and throws up questions. Without human input would AI generated music even exist? How much AI augmentation robs music of its humanity? What is human? If we can’t create, connect and express our inner worlds through music and the arts, how do we leave our mark on the world? Who are we as humans?