2017 then saw a rallying cry. The “Save Womanby Street” campaign pulled both public and political support whilst the “Reboot The Moon” campaign by workers of the Full Moon established a new venue from the ashes of the old one. The political moves made – especially in response to the upcoming Cardiff Council elections – strengthened legislation and even direct action helped the music scene in Cardiff recover. A building set to threaten Clwb Ifor Bach was taken over by Cardiff Council to protect it – rather than it being turned into flats. An “agent of change” principle was implemented into Welsh Government planning policy. The Moon re-opened under the guidance of the forward-thinking “Creative Republic of Cardiff” and the much feared Wetherspoons hotel has still yet to open. Even noise complaints made against Fuel Cardiff thankfully failed to affect the venue, and so Womanby Street remained the home of music in Cardiff, instead of becoming a ghost street.

A resurgence of Cardiff music began. Tiny Rebel (formerly Urban Tap House) opened its own music room, Blue Honey Café started to host music nights and Hub Festival in 2017 marked one of the best years in its history, drawing in huge crowds who had become more aware of the music scene after its slip into peril.

The year ended with the announcement that Cardiff would become a “Music City” under the newly elected Cardiff Council. The city council would work with a consultancy company called “Sound Diplomacy” whose previous work has included strengthening the music of cities like Vancouver in Canada, Barcelona in Spain, Brisbane in Australia and San Francisco in the US. The yearlong consultancy would assess the strengths and weaknesses of Cardiff as a city in relation to music, from education to grassroots music to large-scale events.

2018 saw the continuation of Cardiff’s music growth across the UK – especially in the form of bands like Boy Azooga, Estrons, Himalayas and Buzzard Buzzard Buzzard – and it seemed the scene could only get stronger. Cardiff itself became more prominent in the wider UK scene; accepting more live shows and tours on the bills of venues from the Principality Stadiums to the smallest of the “toilet venues” (named after the idea that you would change in the toilet for a gig rather than a dressing room). Hub Festival returned and the prestigious Sŵn Festival transferred to the promoters behind Clwb Ifor Bach after 11 years of independent success. Clwb Ifor Bach also expanded its remit also, booking bands such as Mogwai in St David’s Hall and Low in Tramshed.

Then towards the end of 2018 it was announced that one of Cardiff’s smallest – but most loved – venues Gwdihŵ would close. The block of buildings where Gwdihŵ is situated is one of the last areas of Cardiff centre not to be redeveloped or modernised, and although the venue had been threatened by many of the issues that music venues face, it appears that the potential profit to be made by its landlord has closed the venue in the end. Echoing the Save Womanby Street campaign, a petition was filed and an online campaign started to save the venue. Gwdihŵ will remain open until the end of January but after that, its fate remains uncertain.

Then, as 2018 turned into 2019, another venue announced it had closed. Buffalo Bar on Windsor Place in Cardiff was less a music venue in 2018 and more of a bar and club. Nevertheless, under various managements the venue had hosted various acts big and small, from Adele and Disclosure to the newest up and coming bands in Cardiff. The venue had a back and forth relationship with music over the years, but always hosted it in some form or another. It was mainly known in its later years for hosting one of Cardiff’s most popular club nights “Bump & Grind”, a hip hop/r’n’b party that never failed to sell out every Monday. With 2019, it was gone, and a legacy gone too.

What had closed Buffalo? Their final post indicated high business tax rates – especially those given to bars and restaurants (there is no business rate specifically for grassroots venues) – and high rent were the death knell, matched in part by not enough custom to the venue. The business rate for Buffalo was £115,000 a year – only outmatched on Windsor Place by the Wetherspoons “Central Bar” at upwards of £180,000. Outrage at two closed venues in quick succession was fair but possibly misdirected. The public turned to the city council, wondering what they were going to do about both Gwdihŵ and Buffalo closing and what had happened to Cardiff becoming a “music city”.

Sadly, the issue does not lie solely in the hands of a city council. Both Gwdihŵ and Buffalo were affected either wholly or in part by their landlords; private entities with no public accountability to a council. In fact, Gwdihŵ was set to be protected by the council alongside its neighbours in its status as one of the last original areas of Cardiff. Perhaps anticipating this, the landlords who owned the buildings decided not to renew the leases for the occupants so they could demolish the buildings before they could be protected.

Business tax rates (set by the Welsh Government) affected Buffalo and continue to affect existing music venues across the country. Elsewhere in Wales, The Parrot in Carmarthen closed for good at the end of December and the Muni in Pontypridd closed as well with its future uncertain. Even further afield, the DIY Space For London (which The Moon in Cardiff somewhat echoes) is under threat of closure due to a quiet summer in 2018 and rising rent. There is a lot that threatens music venues across the UK and even the world. However, the action that Cardiff Council took in 2017 to help protect the music in Cardiff is far more than other less active bodies have done. In London across ten years from 2005 to 2015, music venues in the city dropped 40%. Thankfully, since then both Mayors Boris Johnson and Sadiq Khan have taken massive steps to improve music & culture in the city.

What can be done for music venues in Wales and beyond? Setting a new business rate standard for music venues might alleviate some of the pressure for music venues. Dropping the rate for music venues in particular is key to protecting grassroots venues and could in turn see more being created in the long-term. As for the Sound Diplomacy report, it has been handed over to Cardiff Council and is currently being considered, however public backlash to the recent closures may drive a wedge between Cardiff’s councillors and their constituents. The sooner the report is published and the council’s response is known, the sooner the landscape in Cardiff can recover. How much the council can do with the financial pressure that already exists after years of cuts levied by central government remains to be seen, but a promise made at the end of 2017 should be honoured.

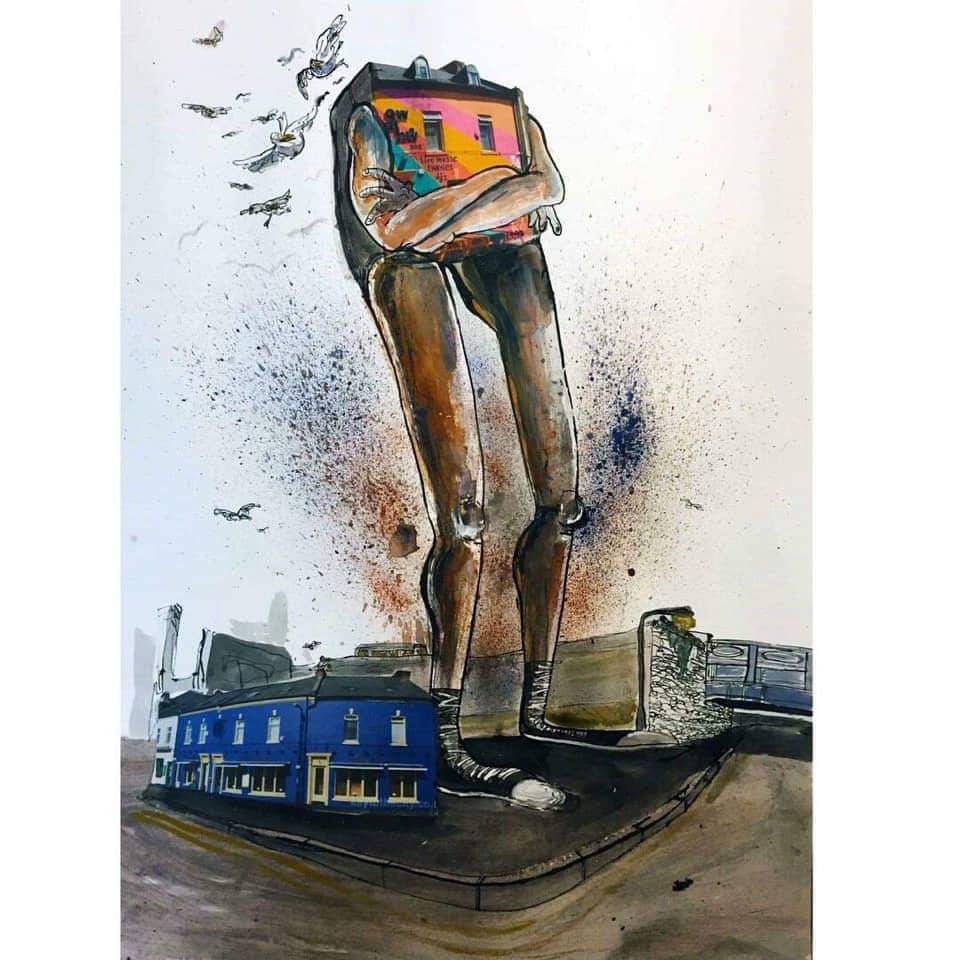

Illustration: Jack Skivens