“Do you know what you’ve done?”

“Yes. I just shot John Lennon.”

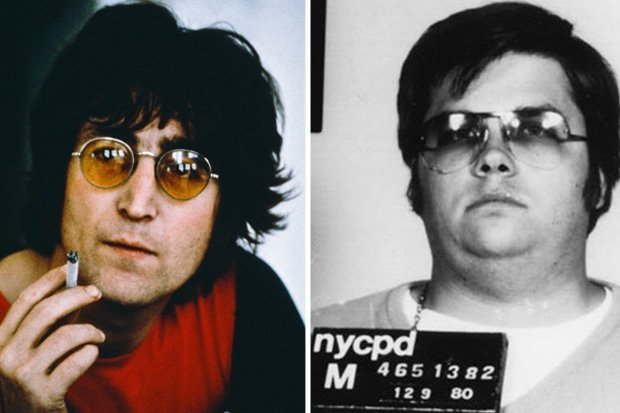

The 8th of December will mark the 40th anniversary of John Lennon’s brutal assassination in New York. This August, by some quirk of fate, will also see his killer, Mark David Chapman, launch his 11th bid for freedom from a 20-year-to-life prison sentence. Considering what the anniversary will no doubt mean to Lennon’s family and friends, as well as to the millions of music fans the world over, the parole board due to sit in New York to consider Chapman’s new plea, cannot contemplate releasing him this year, can they?

At about 10.50, on the evening of the 8th December 1980, Mark Chapman stepped from the curb outside the gothic Dakota Building opposite Central Park, walked just a few small steps, turned and took up what the police describe as the classic “combat stance”, before calmly and coolly calling out to the man who had just strode by, who had just glanced at him inquisitively, and who had, hours earlier, happily paused to sign an autograph for him.

“Mr Lennon,” Chapman is reported to have called out, before firing 5 hollow-point bullets from his Undercover .38 Special revolver. The first bullet smashed a window but the other four slammed into the back and upper left arm of one of the greatest songwriters and performers the world has ever known. Then, as Yoko Ono screamed desperately for help and tried to comfort her dying husband, a still remarkably calm Chapman leaned back against the wall of the apartment block and returned to reading his well-thumbed copy of, The Catcher in the Rye, in which he had scrawled the words: “This is my statement”.

“Do you know what you’ve done?” Jose Perdomo, the doorman on duty at the Dakota that night, asked him. “Do you know what you’ve done?”

“Yes,” the killer replied matter-of-factly, slowly removing his hat and coat in preparation for the imminent arrival of the police. “I just shot John Lennon.”

Five shots, four gaping bullet holes, and the world would never sound quite the same again.

At his last hearing two years ago, Mark Chapman quietly recounted the events of that fateful night yet again. He told the parole board about finally acquiring an autograph from the former Beatle, from his one-time idol, when standing outside the star’s home, and of how he had returned to the very same spot to kill him just a matter of hours later. Chapman told them of how he battled with his demons, of how he had begged God for the strength to just walk away, to fly home, back to Hawaii. Chapman told them of the constant struggle he fought, as to whether or not to go through with the murder.

“I was too far in,” he admitted. “I do remember having the thought of, ‘Hey, you have got the album now. Look at this, he signed it, just go home.’ But there was no way I was just going to go home.”

In an interview given to Larry King in 1992, Chapman revealed that Lennon had been very kind to him during that first fateful meeting. “Ironically, very kind and was very patient with me,” he told the television host from Attica Prison. “The limousine was waiting… and he took his time with me and he got the pen going and he signed my album,” a copy of his latest release, Double Fantasy.

“He asked me if I needed anything else. I said, ‘No. No, Sir.’ And he walked away. A very cordial and decent man.”

“Are you sure there’s nothing else?” Lennon is said to have repeatedly asked, almost as if he had known? Something that Chapman admits to pondering on when alone in his cell. He wonders now if Lennon had perhaps sensed that there was something suspicious about him, something strange and sinister about the man still waiting outside the apartment building that night?

Today, Chapman calls the murder his “senseless” act and admits to knowing full well that he was only seeking out notoriety and fame, insisting though, that he felt no personal ill-will towards the rock star who had just emerged back into the spotlight from a 5-year hiatus, with a brand new album and a whole new outlook to life; happy and content. Nevertheless, and as reports have shown, Chapman chose to use a hollow-point bullet for the task, far deadlier than any “regular” bullet.

“I secured those bullets to make sure he would be dead. It was immediately after the crime that I was concerned that he did not suffer.” But, as he admitted to the board in 2016, he finally felt regret for the actions he had carried out, and for the pain that he had caused.

Photographer and longtime Lennon fan, Paul Goresh, was to capture their first meeting that day when he took that now-famous image of the killer beside his chosen target; Lennon, head down, signing the cover of his new album, and Chapman, smiling, standing calmly beside him, just in frame.

Chapman has repeatedly claimed that he tried to get the photographer to stay, and that he had begged another young Lennon fan who had been loitering around the building’s entrance to go out with him later that night. He even goes so far as to suggest that if the girl had accepted his invitation, or if Goresh had stayed, as Chapman had so desperately wanted, then maybe he would not have gunned down Lennon that night… But, when pushed, he also freely admits that he probably would have tried again, on another occasion, on another day. That he was by then already, “too far in”.

For the parole panel little then had changed over the last 38 years. In their view he was clearly still revelling in that same notoriety originally sought, and basking in his infamy, that he was still so obviously enjoying all the attention it brought, despite claiming to be burdened by guilt.

“Thirty years ago I couldn’t say I felt shame… I know what shame is now,” he insisted in 2016, according to the written transcripts of the meeting. “It’s where you cover your face, you don’t want to, you know, ask for anything.”

The three-person panel, ever conscious of the loudly expressed feelings of politicians and always wary of the mood of a still outraged public, as well as being seen to be mindful to the concerns of John’s widow Yoko Ono – whose letters to them at every hearing speak of the constant fear for her safety and for that of John’s children, Julian and Sean – was still not to be convinced, reminding him that that evening he had, in their words, “admittedly carefully planned and executed the murder of a world-famous person for no reason other than to gain notoriety… While no one person’s life is any more valuable than another’s life, the fact that you chose someone who was not only a world-renowned person and beloved by millions, regardless of the pain and suffering you would cause to his family, friends and so many others, you demonstrated a callous disregard for the sanctity of human life and the pain and suffering of others.” They informed him of their decision to reject his appeal again in writing and concluded that, “Your criminal history reflects that this is your only crime of record. However, that does not mitigate your actions.”

The board also went on to reiterate their concern that Chapman’s release could put the public at risk, voicing the very real fear that someone may attack him in search of revenge, that his release at that time, “would be incompatible with the welfare and safety of society and would deprecate the serious nature of the crime as to undermine respect for the law”. Two years on, as we approach another milestone anniversary, has anything changed that could conceivably alter their collective decision?

Chapman claims that he is now a born-again Christian. He is said to be a model prisoner at the Wende Correctional Facility in New York State. He has earned trusted responsibilities and with that comes tasks that he carries out with pride and diligence, including cleaning, painting and removing wax from the prison floors.

His supporters, including his long-time wife, Gloria, and friends who claim to have known him since long before he carried out the dreadful deed that December night, and who claim that he possesses a gentle and generous soul, have convinced themselves that Lennon himself would have wanted Mark to be free now, pointing towards the star’s well-known thoughts about forgiveness and for reconciliation. And, as incredulous as it sounds, Gloria even suggests that if Yoko and Paul McCartney were to take the time to meet with Mark now they would like him? But can society ever forgive this man? Does he have the right to even ask for society’s forgiveness?

One person who adamantly believes not is Herb Frauenberger, a former New York cop, who, along with his partner Tony Palma, arrived at the Dakota apartment building just minutes after the shooting. They were to find Lennon facedown, having somehow managed to crawl up 5 steep steps and into the reception area.

“When we got inside, we saw a man lying facedown with his arms outstretched in a pool of blood,” Frauenberger remembers. “We approached and, when I saw the blood, I wasn’t even sure if he was still alive; there was a massive amount of blood.” Frauenberger claims that he then turned Lennon’s head and tried to see if he had a pulse. He did, but it was faint.

Immediately realising the severity of his injuries the two officers decided not to wait for the ambulance, that there was simply not the time left to waste.

In an interview given to his local newspaper, The Altamont Enterprise, in 2015, the by then retired cop told them: “One of the other units had called for an ambulance but it was eight minutes away and that wouldn’t work. So, we took his legs and his arms and we carried him like a sack of potatoes to the police car outside. We really had no choice,” Frauenberger insists. “It wasn’t something we would do under normal circumstances, but this wasn’t normal circumstances.”

Frauenberger and Palma’s radio car was hemmed in, so they had no choice but to carry Lennon to a car that would be able to get out, that would be able to navigate through the already growing crowd of shocked and disbelieving on-lookers massing around the Dakota, into a car where they laid him along the backseat as gently as possible.

“We told those officers to take him to the hospital and we would follow with Yoko.”

Another officer, James Moran, is said to have then asked the fatally wounded star, “Are you John Lennon?”, to which Lennon nodded and apparently replied, weakly, “Yes.”

According to another account, this time given by Moran’s partner, Bill Gamble, Lennon nodded slightly when asked his name, trying to speak but only managing a, “sort of gurgling sound”. It was shortly afterwards that the singer-songwriter apparently lost consciousness, as their squad car sped off towards the nearby Roosevelt Hospital. He was never to regain it, in spite of all the best efforts.

Herb Frauenberger also relived for the newspaper the moment a doctor delivered the devastating news.

“The doctor who had been working on him came out and looked at me and he didn’t even have to say anything; I knew… He told me they couldn’t save him.” The doctor then went to notify Yoko, who Frauenberger recalls as being in total and absolute shock, screaming out, “No!”, and refusing to accept the news, insisting that there had to be a mistake.

Of Chapman, Frauenberger clearly recalls catching a glimpse of him later that night, when finally back at the precinct, and of hearing about him repeatedly apologising to other officers for, unbelievably, “ruining their night”.

Chapman was, apparently, just sitting in the precinct handcuffed, calmly chatting without an apparent care in the world, “like he had no emotional reaction”, despite the utter chaos erupting all around him, all over New York and all over the world as the news got out.

“He just looked like a normal, every day guy,” Frauenberger told his local paper. A normal, everyday guy who had just slain arguably the most famous rock star in the world. Can any parole board, especially this year, dare to release Mark David Chapman?