Published last week in an interview with Music Ally, Spotify CEO Daniel Ek’s misjudged remarks that appeared to treat artists and musicians as mere “content creators” as he demanded more and more “continuous engagement”, they sounded like the clinical kind of directives an unscrupulous sweat shop owner would trot out, it also revealed just how out of touch he is and the double standard at the heart of the broken Spotify model.

“There is a narrative fallacy here, combined with the fact that, obviously, some artists that used to do well in the past may not do well in this future landscape, where you can’t record music once every three to four years and think that’s going to be enough.” he remarked “The artists today that are making it realize that it’s about creating a continuous engagement with their fans. It is about putting the work in, about the storytelling around the album, and about keeping a continuous dialogue with your fans. I feel, really, that the ones that aren’t doing well in streaming are predominantly people who want to release music the way it used to be released.”

Reflecting upon how Spotify and the streaming model has obviously changed the frequency of releases and the way artists engage directly with their audience, as seen by the increased speed and length of releases by the likes of The 1975, Ed Sheeran and Taylor Swift in recent times. But given how the Spotify model doesn’t work for most artists, this billionaire tech exec is in no position to demand more and more for less and less. His patronising comments were rightly rounded on by artists who rebuked him for putting a deluge of “content” that suits the Spotify model over artistic creation, that fails to understand the finances required in a funding recording, in investing in instruments and travel costs, thrown into even more sharp focus by the lack of a live music circuit due to Covid 19.

As part of a long and fantastically detailed Patreon post entitled “Music vs Daniel Ek” Zola Jesus commented that “(the billionaire CEO of Spotify) is saying that musicians need to look at themselves less as artists and more as content creators. We have no muse to serve but the marketplace, and without adhering to the rapid heart rate that is Spotify’s demand for new food for their algorithm, our careers are bound to perish. His lack of awareness about what it takes to write and create music is sort of strange given he’s the founder of a music streaming platform. You’d think somewhere in there would be a person who is a fan of the arts, and thus sensitive to the realities of what it means to make art.”

Holly Herndon tweeted her dismay at Ek’s comments. “I want to spend my time getting better at music, a craft I have dedicated my life to. I have very little interest in “continuous engagement”. I find it to be a distracting imposition. I want for every record to be rich and fecund enough to do that work for me. ”

Ek continued in his interview: “Even today on our marketplace, there’s literally millions and millions of artists. What tends to be reported are the people that are unhappy, but we very rarely see anyone who’s talking about… In the entire existence [of Spotify] I don’t think I’ve ever seen a single artist saying, ‘I’m happy with all the money I’m getting from streaming.’” adding, “In private they have done that many times, but in public they have no incentive to do it. But unequivocally, from the data, there are more and more artists that are able to live off streaming income in itself.”

Zola Jesus rejects this idea, disputing Ek’s claims and arguing that the Spotify algorithm rewards a certain kind of sound. “Really? Because as a musician I have not met a single peer that is satisfied with the income they get from streaming. In fact, the only ones who could potentially live off the income are the ones who are either already very successful, on a major label, or are making music that is rewarded by Spotify’s algorithm. It’s no surprise that certain music does better with streaming — anything that can be put on a “chill out” playlist, that’s easy enough to listen to, thrown on in the background while you’re cooking… but that music isn’t music as much as it’s muzak. The artists that are attempting to create something new, different, or deeper than what is required to make it onto one of those playlists… the real culture creators cannot survive. Because the system isn’t made for them. Spotify even has a special metadata set for “valance” – in that, they rate the happiness of a song and this helps drive what playlists it would go on. Which means, if you’re not making music that makes people feel happy, good luck getting heard.”

Ben Sizer argues that there are clear financial reasons why not every artist can ‘continuously’ release new music “I wonder if Daniel Ek realises that bands like mine only release records every 3 or 4 years because we have to fit it around our day jobs – jobs we need to pay the bills precisely because streaming services underpay artists.

The band Beauty Sleep also tweeted about a relevant and dangerous issue, how the constant creative pressure of being a independent artist, the pressure to constantly engage with your audience and promote yourself, whilst touring and recording often alongside a full time job can affect mental health too: “This kind of rhetoric hurts my soul. You just gotta be on it, all the time, build, engage, more content on all platforms, fund it yourself, keep going, dont stop or it’ll go away. No wonder musicians mental health is in the toilet. This leads to burnout & bad art dont fall for it.”

Zola Jesus continued to dissect how Spotify works ultimately for Spotify’s profit margin. “This model works for Spotify and Daniel Ek, because Spotify requires the labor of artists to generate their content. It is not in their interest to give artists a break, because we’re the ones that are driving the entire system. Without new content, there’s no new traffic. In Daniel’s world, it is a numbers game. The more artists the better. The more songs the better. The more content, the more profit. But we cannot ignore the consequences of a market saturated with shitty music. …Or the subtext of why Spotify is moving towards podcasts and away from music. Music is inherently an art form that requires space and time; time to make and time to listen. It’s not like a podcast, which exists under an entirely different scope and timetable.”

Ek concluded with “As you very well know, a lot of the income today that artists are getting [pre-Covid-19] is from touring and live performances. A lot of artists are struggling because of that.”

Zola retorts “Interesting that Daniel is cognizant enough to see the impact that touring has on an artist’s financial stability today. I’d like to ask Daniel why is it that touring has become the backbone of a musician’s income? It can’t possibly be because he’s created a platform that has exploited the work of artists and not properly compensated them, so they’re forced to slog it out on the road 10 months a year. Don’t forget, we’re also supposed to be putting out two records a year on his schedule.”

It is becoming ever more clear that Spotify is not a place for artists or musicians, but for content creators intent on dumping their incessant stream of product into a saturated market for the algorithm to chew up and spit out. In my meager opinion, nothing is worth listening to under those standards.”

Some of these shifts are driven by streaming culture and the appetite instant consumption, but Ek’s demand upon artists to produce more and more content has led to Spotify outsourcing and had the affect of making playlists more important than artists on the platform at times, it has also diluted the quality of music as we are deluged by a saturated market increasingly stripped of old music press gatekeepers and reliant on algorithms. Who can possibly listen to their multiple specifically curated new music playlists every week? I know I can’t. Richard Pike, of the label Salmon Universe Records remarks: “Playlisting’ makes artist connection quite anonymous too, which has been highlighted by the well-known fact that Spotify funds and owns numerous ‘fake artist’ accounts. I run a label mainly involved in ambient and experimental music. It is upsetting to be involved with the worldwide ambient community to open a Spotify ‘Sleep’ playlist and not recognise one artist (because they are made up names).

Aside from that, I can’t count the number of times I’ve been at a venue, party or barbecue and I ask the host about the artist playing from their Bose Soundlink to see a shrug of the shoulders and ‘I don’t know, I just put on a playlist’. The platform breeds the opposite of engagement. In terms of my small label, I can tell you for a fact that Apple playlisting has paid much more than anything that has happened on Spotify for us.”

Mike Turner of Happy Happy Birthday to Me Records points out: “Music is nothing but admin work these days and the line of tech middle-men who produce and create nothing all standing in line to dip their hands into the artists pocket is just never ending. It’s really rich to have some code-bro tech douchebag to just solve all the artists problems with maybe not making a living at music. You just have to make more music and product. It was that simple. I figured artists were having trouble making a living considering tech has devalued music to the point where younger generations see no problem in it being free 24/7. I’ve never been a fan of the service, but the recent addition of a tip jar that was set up for artists during COVID-19 was even more insulting. Give it a few more years and most of the playlists will just be filled with AI making the exact sounds that people want based on algorithms.”

An immensely popular and very useable application, Swedish streaming giant Spotify has made streaming the central way many people access new music in today’s world over the last ten years, and certainly as a consumer even one like me who is still invested in owning records, it is very handy and convenient. Its development came in response to illegal downloading from the likes of Napster, and the failure of companies like Apple.

The issue is their model only works for a tiny fraction of those artists and labels on the platform. It has also created a devaluation affect for recorded works and an expectation that music should be virtually free (with ads) or only ten pounds a month, not nearly enough to properly reimburse artists. In a recent interview with us, Tom Gray recently talked about the Broken Record model. “Here are the money splits from streaming: Streaming company keeps 30%. The Recording gets 57%, the Song gets 13% (of which publishers get 20-25%). So that’s 8-10% that goes to the writers of which, on any song, there may be multiple. What an artist earns from that 57% varies enormously.

A few self-releasing and successful artists do very well out of this situation. But most artists labouring under Major Label contracts are unlikely to make as much as 50% of it. 20% in most cases. When you consider how little the money earns from each stream (approx £0.005 per play), you need a lot of plays to make any kind of money.We do not get a fair cut.”

I’d like to talk more about how the consumer is being let down. How their money doesn’t go to their choices, and how streaming is unsustainable in the present situation, and will ultimately lead to them losing choice. 80% of an average Spotify listener’s money goes to music they do not listen to.”

But what is the solution? “Increasing the amount we pay for streaming marginally: Stop saying it’s price-sensitive; Kids pay £8 for a skin in Fortnite and we can’t ask for £12.50 for the entirety of all recorded music? Give me a break.

As for the independent labels go 50/50 with your artists across the board. It was always the ethical way.We need to support our record shops through their online businesses.”

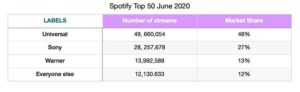

1% of artists whose work earns 90% of the income from streaming. It *still* means if 75% are major artists then the figure who are actually making a decent living (on average) is still only 11,000.

that “according to Spotify’s Q2 results, the firm generated €1.89 billion ($2.05 billion) in the three months to end of June. We can therefore broadly assume that 52% of this money, or $1.07 billion, is being paid in recorded music royalties to labels and distributors, who will carry a portion of that over to their artists.

Now, if 43,000 artists are pulling in 90% of the royalties, that means those people are getting $963 million of the $1.07 billion. As a mean average, that’s $22,395 per artist, per quarter.

A salary of around $90,000 a year can certainly provide the average “top tier” Spotify artist with the “opportunity to live off their art.” But this is skewed in itself, of course, because across the 43,000 “top tier” artists, the majority of the $963 million would actually have been captured by the world’s biggest superstars. (And that’s not to mention how big of a cut the labels and distributors are commanding via individual artist deals — some of them slicing quite significantly into the totals.)

But what about everyone else who isn’t in the so called ‘top tier’: “We know that Spotify had over 3 million creators on its service in 2018, and that this figure is likely considerably larger today. Yet even relying on this conservative 3 million number suggests that 98.6% of the world’s artists — i.e. 2,957,000 separate performers — are currently operating outside of Spotify’s “top tier.”

Well, we know that they share 10% of Spotify’s recorded music payments (outside the 90% of streams claimed by the “top tier”). And, according to our estimates here, in Q2, we know this 10% amounted to $107 million in royalties. Divided amongst those 2.96 million artists, this means the average non-“top tier” Spotify artist earned just over $36 in the quarter. Or $12 per month.”

The second flaw in Spotify’s aim to provide “a million creative artists the opportunity to live off their art” is tied to the pace of growth amongst the size of the firm’s “top tier” artist group. It seems like in order for creators on Spotify to “live off their art”, they also have to enter the “top tier” of artists sharing 90% of streams on the platform. If so, Spotify won’t satisfy its own mission statement — Daniel Ek’s central visionary, democratic aspiration — for three-quarters of a century.”

The artist Bryde tweeted that streaming is clearly the reality and is not going anywhere, but a platform can’t dictate the pace of creative process. “I use Spotify and streaming in general and there’s no going back, but business people should not be dictating how artists make art. Advice on marketing? Sure. But keep your hands off our creative processes. They are as unique as the music we make.”

There are success stories when it comes to streaming but they are very few and far between. The band Tugboat Captain explained “As a band we’ve benefited greatly from Spotify with continued exposure from playlists and therefore income we most likely would not have otherwise been able to garner. That said those benefits are basically only evident because we’re totally DIY and independent and keep every penny of our streaming income. The danger of that though is the psychology of working towards Spotify and fighting against the urge to write music that would cater to that – our song ‘Don’t Want To Wake Up My Own’ is our most popular track and in hindsight is perfect for play listing. Although it was never written with that intention, the attention that track has gained through algorithmic play listing has definitely had a massive effect on the way we approached making music and its very difficult to shake that and remember that what you make is an art form… I could ramble forever on this haha but thats basically my two cents. Ek is out of touch and the streaming model doesn’t work for artists as it currently stands – the only alternative is raising the cost of Spotify and redistributing the income made on streaming. And of course also encouraging people to actually buy physical releases!”

Aidan Stevens of You The Living remarked on facebook: “I think he made a good point in the worst possible way and in the worst possible context. The traditional “an album every three years” routine just isn’t compatible with modern sensibilities.

When YTL released an album, it flopped in comparison to when we just released singles and EPs every few months to a year. “Little and often” is much more engaging these days. That’s why we’re releasing our second “album” in chunks.

Rebekah Delgado differed arguing that art can’t always be rushed or the quality will suffer. “With that way of thinking we’d never have had Leonard Cohen! People work at their own speed and good artists need fucking investment or at the very least get paid if people like what they do.

Lou Reed used to write songs like a machine but in the end it was the quality not the quantity he put out there. Art almost always reflects the changes and upcoming changes in society before anything else. First it was music, then writing (journalism you will relate to). Jobs becoming automated were affected in factories decades ago but the general idea I’m trying to push is there needs to be a different model for the future of almost every livelihood as technology escalates.

Netflix and Amazon etc are investing in art in innovative ways and changing everything so there *could* be a different model for music.”

Spencer Segelov remarked in a similar vein “Whilst the proposed increase in release schedule suits someone like me, most musicians are not that prolific and also the more one puts out, the less the public is interested – Prince is a good example, people can’t keep up.”

Scott Causer of Northern Star label tells us he isn’t suprised by the Spotify CEO’s remarks: “Daniel Ek telling musicians to create more content to feed his site is not only taking the piss, but showing how entitled he is and how out-of-touch the rest of the industry is. However, what do you expect? He’s a billionaire programmer, not a struggling musician. The part I really fail to understand is musicians and indies are going in like lambs to the slaughter, giving them their art for a pittance and then shouting from the rooftops complaining about them whilst fully knowing what the outcome will be.

Spotify sucks as do most streaming services. The sound quality is iffy. The algorithms are all geared towards promoting the most popular musicians/labels. The three biggest labels have priority on the playlists which you have to pay to get on. The remuneration is a joke. Most musicians will know or should at least be aware by now that you need 10s of thousands of plays to earn enough for one beer with 4 straws for you and your band to share. However, there is still a myth that persists that musicians and labels are making tons of money. So for me, the fact that musicians and indies are putting up with this is completely unfathomable.

As a label owner and musician I took all of my music and our bands music off there a long time ago. Firstly, we were making nothing off digital services and putting full albums on there was severely impacting sales. Secondly, I’d be asked by bands for a full rundown of their streams, which is just not possible when you’re making your own music, running a label and holding down a day job too. I never got into rock n roll to become some band’s admin assistant, so I gave the digital albums back to the bands to let them manage theIt releases themselves while I concentrated on physical product.”

Retaining value in your music is important and not just rushing your work straight onto Spotify, maybe a more staggered approach is needed. He argues more strongly that changes need to happen “Streaming services do have their place, however that place should be limited to promotion only. The system is rigged. You’re never going to win them. They don’t value your art, so why value theirs? Now it’s time for independent musicians to reevaluate their strategies. What I do now is put a song or two on there as ‘singles’ for promotional purposes and point them towards my own site. If people really do value your music they will buy it direct off you. If they don’t, they won’t. However my concern really centres around the fact that this whole approach is completely unsustainable. Musicians and indies should be taking a stand as feeding a service that shafts musicians is quite frankly, foolish. Putting all of your music on a site that doesn’t give a fuck about you or the value of your music is tantamount to killing the culture you purport to love.”

“As musicians and indies, we create the content, therefore we have the power. We need to take a stand and take responsibility, because if we sit round feeding the system that’s fucking us over then when there’s nothing left, we’ll only have ourselves to blame.”

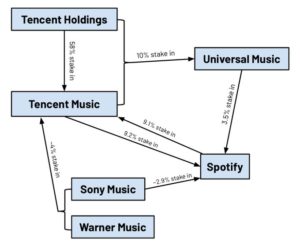

The Damnably label explains how major labels and big indie labels have a leg up when it comes to distribution and thus streaming numbers on the platform. He believes due to their links to the platform. “Spotify has become part of the goals labels are meant to chase so PR + radio pr = playlists and income but the system is not a level playing field so majors and indies that are actually sub labels of majors will get 10/20 times the streams even if the pr/radio/fanbase is the same. Indies can’t get a fair go from this system and we actually aid Majors hold on us via indie distribution as that is now mostly owned by majors, like Orchard was bought by Sony, even the ones that seem like Indie distro are using companies owned by majors and that’s a big problem. Indie labels could outperform Majors if we didn’t give a % of our income back to them for them to further control the whole music industry. So Spotify is very good for majors and their sub labels as they are taking money that should go to indies and that’s before thinking about a fair payment. Indies need entities like AIM to fight for them as the Muscians Union are and they really need a totally independent digital distribution system and even a DSP or version of Spotify that’s build to give 90% of the income to acts/labels like Bandcamp.”

Image courtsey of Cheri Hu.

The streaming figures prove that a massive majority of streams are of tracks from the three major label artists, they get prominent placements on playlists and on the platform, it’s a gamed system. He continues: “The general thing of renting music is a step back and Spotify playlists are incredibly bad, so it’s an awful system that only rewards those in power who manipulate it like Festivals, Awards, Radio playlists etc and the pandemic is showing that Majors/Sub labels are trying to claw back the lost money so Spotify and the whole industry will only get worse in terms of indies and acts having a fair shot.

“It’s quite interesting that while the overall pie is growing, and more and more people can partake in that pie, we tend to focus on a very limited set of artists.”

The Anchoress tweeted some tips if you are looking to get more streams and followers on the platform: “Getting on playlists is considered to be the holy grail but when you dig deeper into the numbers it doesn’t always add it (up?). If you aren’t converting playlist listeners then they are just fans of the playlist, not fans of you. The algorithm knows this. Pay attention to your followers to monthly listener ratios. If you’re around 10% apparently you are doing pretty well.

I was amazed to find mine up at around 33% – this means I have a very engaged fanbase of true listeners (no padding here!). Make a playlist that has your entire catalogue in it and whenever you release a new track, add it to the top.

Make this playlist the one destination that you send your fans to. Point everything here and pin these to your artist profile.Add a note to your calendar to refresh your “Artist Pick” every two weeks.

This can be anything from pinning your latest track, new show, to sharing your carefully curated playlist of sad summer songs to slowly go mad to.”

RecklessYes co-founder Sarah Lay explains how they structure their releases in the era of streaming: “For us as a label this means considering carefully the poor financial rewards and ethics of encouraging our artists to have their music on streaming platforms against the other parts of the industry it turns the wheels of – streaming figures interlink with coverage, and with bookings, and more. But streaming is less to do with discovery than many assume, and more to do with convenience for existing fans in most cases. Yet even with insulting payment models there are broader reasons to consider streaming for artists.

She expands on how they are retaining value in their releases: “Rather than pulling music from the platform we’re thinking differently about releases and will only partially release across these platforms for many releases in the future. The full album, or EP, will be available to buy as a download from a platform like Bandcamp (we as a label don’t take any cut of digital from there for our artists and releases), or as a physical product. This is us doing something small toward reinstating the need for listeners to directly pay for music they want to listen to a lot, and do so through means which more directly return money to the artist. If we stream in full it’s more likely to be through ethical platforms such as Resonate who have more respect for the artists, music, and fans.”

Adam Ficeck a professional musician and psychotherapist working with musicians sounds a ominous final warning “We are fast approaching a point of no return for the independent music creators who fuel ‘movements’ and paradigm shifts in the UK music industry.

I acknowledge that there has been a huge change in music industry culture since the advent of digital delivery and how this is in part fuelled by ‘fast food’ style demands of the modern consumer, but it is detrimental! Music and musicians are far more than a quick turnaround opportunity to generate easy income. We are in danger of losing a rich heritage of depth and longevity if a corporate like Spotify are allowed to dictate the rules.”

Ethical streamers like Resonate and Sonstream have emerged offering more ethical streaming splits to artists and labels (we will go into this in more detail next week). Bandcamp has been lauded for its fee waver Friday intuitive during the pandemic and Patreon and other direct to fan services and fan clubs can provide a more direct bridge between fans and artists cutting out the middleman.

The best way to support your favourite artist is still to buy their merch, their records or tickets as directly as you can. Spotify is a very convenient platform but ultimately those who run it don’t care about art or music its a way of driving consumption on their platform. The losses on the books year on year, show why its current model is unsustainable as it is, and is offset by a 2 billion pound share issue in 2018 and the sinking of a hundred million dollars into an exclusive deal with a global podcast from Joe Rogan.

The #brokenrecord campaign is arguing for a better deal for artists and regulations on the streamers, pressure needs to be brought to bare from law makers, artists, labels and fans upon the platforms and tech giants to share more of their wealth made off the back of musicians and art.

We need to reimagine a different future with better models for artists. We need to think about our choices and how we consume music, which streaming platforms we support and how we support the musicians and releases we enjoy, because the current streaming models won’t sustain the quality of music or most of the acts you love in the long term.