I have worked as a tour manager for various bands over the years. This has meant many hours spent hanging round outside live music venues with no real purpose. You may say you feel you would do that for fun, but believe me the hours linger. I have never been so richly rewarded for hanging round outside the Moon in Cardiff during soundcheck than the day Mohamad Kebbewar wandered up to me and asked me about the music he could hear coming from inside one late afternoon. Usually these kinds of short exchanges end in nothing particularly satisfying, sometimes quite the opposite. This was the memorable exception. As we got chatting, and he joked that the music was too loud for his recently damaged ears, it transpired he was a poet from Syria. In town for a film festival, because of my links with music we talked about the performative aspects of poetry and struck up a professional respect for each other and I was excited to learn more about his work and this curiosity has been richly rewarding.

Mohamad Kebbewar was born and raised in Aleppo. Immigrating to Canada at age 19, Kebbewar earned a degree in history from Concordia University in Montreal and it was there that writing became his passion, especially for expressing his diaspora and alienation from a homeland he loved dearly. Poetry helped him express this feeling of being pulled between two worlds yet never belonging to either.

In 2016 Kebbewar took the brave, unexpected decision to go ‘home’. At a time when so many were leaving Syria, he returned to his beloved, “fallen” Aleppo; the city where his parents had proudly stayed. Incidentally it was a failed funding application that took him home. He bought a one way ticket to Beirut and quite ironically artistically flourished when reconnected with a home that had changed so dramatically and severely. He describes everyday life as survival:

“Life [in Aleppo] is difficult and unfortunately it’s not caused from the outside. It’s from within. The collapse of the currency and the lack of life’s essentials have led many young people to leave the country. Stress and anxiety are on everyone’s face. There’s no end in sight in the near future. […] If I compared my life in Aleppo with that of Canada I would say it’s seriously compromised if not shocking. We live below the level of human decency, below dignity. Staying warm in the winter and cool in the summer are our dreams. I am very happy when I have electricity. My mind is super occupied with having running water, electricity, cooking gas and enough money for daily surprises.

Kebbewar recently published two ‘chapbooks’ (a European tradition of a small stitched and bound book of around 40 pages or so) Children of War and The Soap of Aleppo. He has also written a collection called Evacuate. Currently he is working on a semi-autobiographical novel, The Bones of Aleppo. Each collection flows seamlessly, and his love for music, for lyrics, for rhythm is obvious when you read his words.

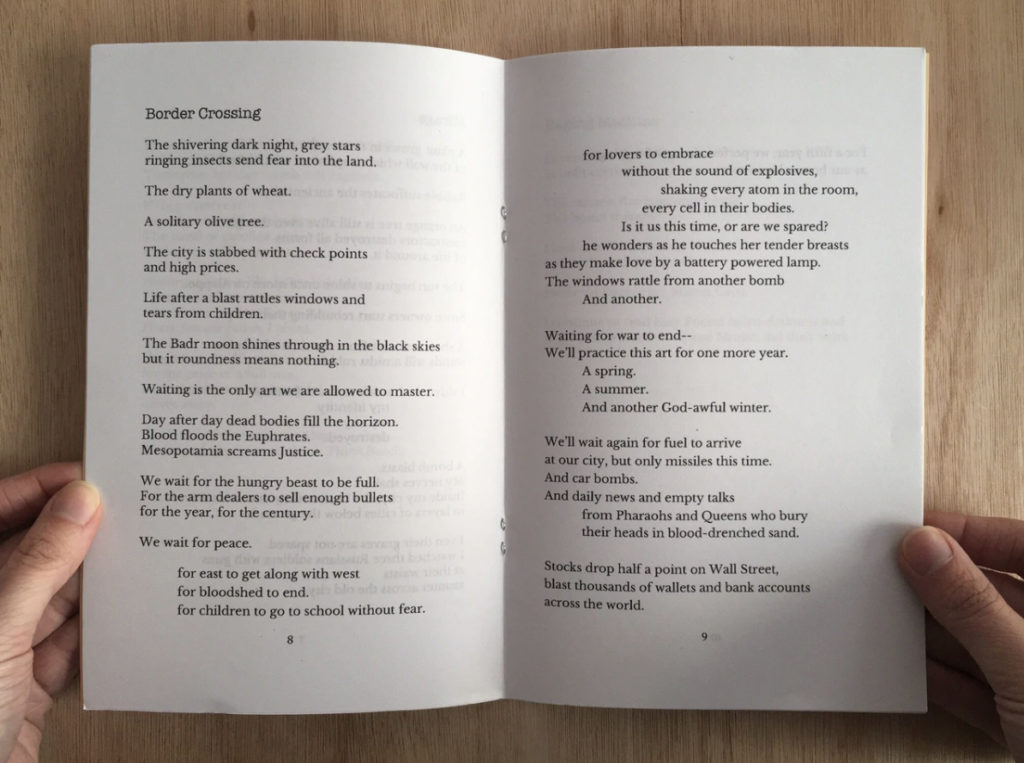

Kebbewar’s poetry evokes strongly the experience of those “left behind” trying to rebuild the country they love and the country they remember. This line from ‘Border Crossing’ (Evacuate) is one I somehow found more striking than anything else on that theme “A solitary olive tree”. It reminds us of a very everyday natural Syrian image, now lonely and stranded. A feeling Kebbewar often says he experiences when feeling torn between the two countries he has lived in: Canada and Syria.

At this crucially confusing and scary time when Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has created millions of refugees, echoing so fiercely what happened in Syria where, according to the UN, some 22 million have been displaced since 2010, it feels relevant and poignant to interview Kebbewar. Poetry has long been an established form of wartime art that truly conveys the more complex emotions of an impossible pain. By talking to Mohamad and revisiting his poetry and artistic reactions to his own experiences of a nation’s trauma, I wonder what we can learn from his experiences and how it can be used to understand more deeply what is happening now and also appreciate more the poetry and art from the besieged Ukraine.

Fascinatingly, a lot of sentiments Kebbewar expresses of destruction and noise by Russian bombs are echoed in similar phrases and imagery by poets who he shares so much with in Ukraine right now. Lithub has published a compelling series of five essays on contemporary Ukrainian poetry which gives such insight into the current artistic climate. For example there are incredible poets like Iryna Shuvalova who are writing in exile from China:

“but death is coming and death is buzzing

over plum trees over cherries and quince

the ruthless stinging of metal bees

spring is coming it’s already spring in nanjing

the columns move toward kyiv military columns” – Iryna Shuvalova

Her words evoke those of Kebbewar’s so directly for me. The concept that there is such longing for quiet as there is constant noise of death. For Kebbewar the noise is more literal: “The sound of each bomb depletes my senses’an ounce at a time” (‘Highway Robberies’, Evacuate).

Another notable poet highlighted by Lithub is Kateryna Kalytko who is active on social media and updates with poetic snippets regularly as she refuses to be forced from her home.

2019

“There are plenty of bullets, don’t spare them,

if they run out—

make new ones out of words,

only slender feminine fingers are suited to such manoeuvres.” – Kateryna Kalytko

(Translated from the Ukrainian by Amelia Glaser and Yuliya Ilchuk)

Boris Khersonsky in his article ‘Every hut in our beloved country is on the edge’ states the importance of poetry and the freedom to write at the time of war. Especially during this Russian invasion of Ukraine.

“In one very real sense, the current war in Ukraine is about language. Vladimir Putin has presented the defense of Russian-speakers in Ukraine as justification for a campaign of cultural and political domination. In an article posted to the Kremlin website last July, he went so far as to compare the institutionalizing of Ukrainian language and culture to “weapons of mass destruction.” Extending the metaphor, he continues: “Such a crude, artificial dichotomy between Russians and Ukrainians may have caused the total Russian population to decrease by hundreds of thousands, or even millions.””

With all this in mind it seemed so pressing to discuss the mechanics of poetry with Kebbewar. Why poetry? How does it help heal a nation by expressing anger and pain? And maybe more fundamentally in the light of Khersonsky’s article, what linguistic choices has Kebbewar made in his career that have been politically influenced? When asked about his decision to write in English rather than Arabic, for example, one reason given is ease of transmission. Kebbewar wants his feelings and his country’s pain to be as easily communicated as possible, particularly to the friends he has left behind in Canada. For him too there have been political considerations as he fears political or state repercussions if writing in Arabic about Syria in a negative light. Interestingly, perhaps because of the need to protect and defend their own culture so strongly, most of the Ukrainian poets Lithub featured chose to write in their native tongue.

During our interview there is also the more concerning issue that I was keen to discuss with Kebbewar about the potentially uneven treatment of refugees that many people have been finding distasteful. The closeted racism of a government paying people £350 per month to take in Ukrainian refugees vs the struggle of Syrian refugees to survive horrific boat, road and foot journeys to anywhere safe has been really problematic. I want all refugees to have a chance at a safe life, of course, and I want our borders open to Ukranians; I just want all other refugees to have equal opportunities.

When I asked Kebbewar for his first reaction to the invasion of Ukraine his words were simple and striking: “Not another war”. He continued: “I saw before me a replica of the Syrian War. Destruction and displacement everywhere.”

Here is our interview in full:

PB: When we first met, outside that music venue in Cardiff, you spoke of

what music and performance and the performative aspect of poetry meant

to you. I would love to explore this with you more….

MK: Performance and the musicality of poetry is an important part of being a poet. The ecstasy of being on stage is irreplaceable. The joy of reading my heart out on stage and watching people’s reaction while reading or after I go down to my table are often the most valuable gift to a poet. When I make an impact on as a few people as four each time I read at an open mic event I feel that I’ve done my job as a poet. Performing poetry also has a social function. I meet new people everytime I read a poem. People are often curious to learn something about the war, to expand their world view, or meet someone from a different culture.

PB: What music do you love, do you ever write to music, read to music?

Do you hear music when you read your poetry, or what do you hear when

you read your poetry?

MK: Even though I don’t play music, it has been a big part of my life. I grew up with classical music listening to the religious hymn of Bach and the passion of Beethoven, and the solitude of Schubert. When we immigrated to Canada in 1996 I got into Jazz music. I love the work of Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Ella Fitzgerald and Louis Armstrong. Later, I got intoMetallica, Guns N Roses, Radiohead, and Portishead. Led Zeppelin. I befriended a couple of musicians who were from Middle Eastern origins doing musical experiments in Montreal. I had a Canadian friend who grew up in Saudi Arabia. He formed a punk band. When I was in Canada I used to write in coffee shops but in a war zone when the act of writing in a public space can be considered suspicious I write at home to silence because silence has been part of the war—the silence of the international community of what was happening in Aleppo.

I had a wonderful opportunity to read with a bass player in Victoria, BC, the chemistry was fantastic. The bass player felt my poetry and blended his music with my words. When I read my poems

I hear the anger of the people who had to abandon their homes. I hear the anger of Aleppo.

PB: Have your ears healed now?

MK: Yes, they are much better now! Thank you for remembering.

PB: What are you listening to right now – playlist wise? Can you include some Syrian recommendations?

MK: Nelly Furtado, Promiscuous

Justin Timberland, Cry me a River

Abed Azrie, Fou de Layla

Bjork, Crystiline (Omar Souleyman)

Pional, In Another Room

Radiohead, The Numbers

Buena Vista Social club

John Coltrane, Equinox

Sting, Desert Rose

Jimi Hendrix, All Along the Watchtower

Syrian Playlist:

Asmahan, Ya habibi taala elhaani

Sabah Fakhry, Khamrat el hob, Qadukka Almayyas

Laure Dakhache, Aminti Bellah

Farid Elatrash, Hebeena Hebeena

Abed Azrie, Etre

PB: Are you still aiming to include your poetry in film making – can you

explain/outline/describe your ideas?

MK: Yes, film poems are much more accessible art form than written poetry. With the increasing role of social media and the decline of attention spans of readers film poem might be more effective in influencing public opinion.

PB: With your draw to performance/music… what is your view of the role

of poetry in literature and society. Is it a folk/oral tradition, is

it political, can it be both?

MK: Poetry is the oldest and densest literary form, it’s capable of abstraction and description. Its deep expression Gives it an edge over other literary genre but all genres are equally important. Poetry can be both folk and political. It can be self-expression or a political statement. I can imagine that my poems will be considered as primary source documents for writing history many years down the road. How one poet saw his country at the time of war, while being there himself.

PB: What poets have you admired as you developed your voice, what

contemporary poets do you admire?

MK: Beowulf, Shakespeare, Emily Dickinson, Seamus Heaney, Sylvia Plath, Ilya Kaminsky, Sheri-D Wilson, Lisa Robertson and Rob Taylor.

I wrote a poem that was inspired by two Shakespearean sonnets.

T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land was an important read as I wrote my collection of poems.

PB: Which poem, do you have a poem, you are most proud of or in an

inverse way perhaps most connected to?

MK: Children of War is the poem I’m most proud of for personal reasons because it’s the first poem I got paid for And it was published by a major Canadian magazine. It made me feel that now I’m a professional writer and that I have reached a new level in my writing journey. If I can choose another poem it would be Pistachio Orchard. I’m most connected to this poem because not only is it about my hometown but also about an orchard that my grandfather inherited, continued to plant new trees in it, we are now as a family several generation later still taking care of the land and reaping its benefits.

PB: What are your barriers – real or emotional – in writing your novel?

Thematically how is it developing?

MK: Writing my first novel has not been easy, in a way it’s my Akeley’s heels. I’ve been writing it for seven years And it still doesn’t want to be done. I went through it not realizing how much structure, organization, and craft It requires. My challenge was characterization and research. I’m going to Sweden next month to do some research about it. It’s a humbling experience to say the least. I can also say that poetry is a much more forgiving genre than fiction. […] My research in Sweden has to do with the last chapter of my novel where my protagonist ends up. I thought it would be interesting to be in the place I’m writing about. To capture the feel of the culture and the refugee’s experience in it.

PB: What would you like people to know about your motives for your writing?

MK: My pride and my pain. My pride in having lived in one of the oldest continuously inhabited city in human history if not the oldest and to continue to be inhabited even after such a long and vicious war. My pain in watching my city destroyed on international news channels, on social media, and later in person as I walked through destroyed neighbourhoods of the old city and lived through the Battle of AlZahraa neighbourhood. . I wanted people to look beyond news coverage and look through a personal lens of someone who is from Aleppo and passionate about its beauty, culture, history, and watch it being destroyed. I want the reader to feel my pain and pride in these poems.

PB: Could you elaborate on one of your quotes for me in the light of current political events: “Europe is young again/highway robberies”? (‘Highway Robberies’)

War is a money making machine. When war happens it create the instability for people to steal national libraries Museums and other treasures. People flee en mass. In the case of the Syrian war they were mostly families with Young people and children. A few years later they entered the workforce. Young people were schooled in European educational system and European culture

PB: It is undeniable that the invasion of Ukraine is relentless and horrific to see unfold. However, in the UK there have been some difficult issues in our country’s response to it that I would really like your take on. Our country has certainly not been unique in its outpouring of empathy for Ukraine to an extent that errs on virtue signalling. It is hard to watch the government offer people money to house Ukrainian refugees in their own homes, however, when refugees from other wars and ecological disasters have been treated like a “problem” and a political tool where it has been important for our right wing government to “keep them out”… It is hard to not see this as racism and in particular cases – Syria for example – islamophobia.

MK: For sure, solidarity with Ukraine means solidarity with Europe. If Ukraine falls then maybe Poland too and the rest of Europe will follow suit. A friend of mine left for Sweden today and she was scared that the war might spread there as well. I assured her that the war won’t reach Sweden, but the point is that Europeans are scared. The war in Ukraine is a war of values between the liberal west and Russia. It helps that Ukrainians are Christians.

At the same time I feel the double standards of many countries in Europe when the war started in Syria and Europe closed its borders at least for the first couple of years of the war. The main problem with Syrians was that they were mostly Muslims, there were Christians too but the majority were Muslims. This is surprising since Europe is mostly secular or at least promoting secularism.

There are no flags of Ukraine. The official position here is that of Russia since Syria and Russia are allies. Most People here sympathize with the refugees and oppose the use of such brute force. Living in a police state, we only have time to think about bread, frying oil, cooking gas, and fuel. We are reduced to life’s essentials so we don’t think about anything else. Most of the people I speak with, and Syrians who live in other Middle Eastern countries, say that Russia is doing a balancing act of world dominance. They also say

That the world is tired of a unipolar system and it’s time for a multipolar system. Like the war in Syria, the war in Ukraine is not an isolated incident, it’s the cold war all over again.

PB: Why did your parents stay in Syria?

MK: It was very difficult for them to relocate because their lives in Aleppo had been very well established. If they did leave they have to go to a country where they didn’t speak the language and knew no one there.

PB: How does a country handle trauma? How has Syria handled trauma, what

are your ideas of how it SHOULD or COULD have?

MK: A country can handle trauma in many ways. Through art and storytelling, improving education so that the new generation help the country stand on its feet, through economic projects. Instead people had to pay the cost of the war. With Covid-19 the currency decline rapidly and the economy was in shambles. Syrians are hard working people, a culture of entrepreneurs and industrialists. the return of essential services like electricity, fuel, and water will help the country heal itself.

PB: War comes again. You have to leave. What do you take?

MK: My clothes, my laptop, and my savings.