It’s always good to encounter a band who act like the nineties and its botched, two-decades-long hangover never happened. Album number three finds Algiers picking up where they left off on 2017’s The Underside of Power, singularly and refreshingly devoid of irony and escapism, unambiguous and confrontational, coming at you head-on with a barrage of earnest, uncomfortable questions.

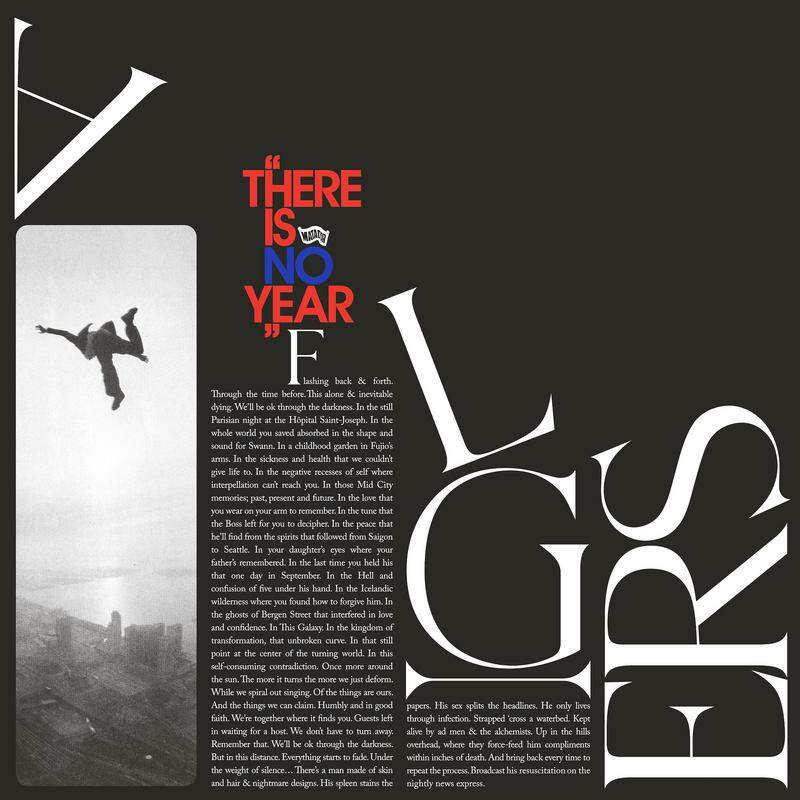

Originally hailing from Atlanta, Georgia, by way of New York, London, Bloc Party, Gillo Pontecorvo, Skype and a lengthy stint as Depeche Mode’s warm-up act, their sound has been unfairly pigeonholed as industrial music meets gospel. Yes, there’s more than a hint of Skinny Puppy, but There is No Year is an album that exposes deep strata of music and history and which has an inquisitive attitude to music-making that perpetually threatens to position Algiers as heirs to Radiohead or even Bowie. Plus, their latest video has the band with their backs to us at the end of a long, dark corridor, performing their new single to the fire exit. What, I beg of you, is there not to like about that?

A big factor in the industrial-meets-gospel misperception is the sure-footed vocals of Franklin James Fisher. Have you ever secretly fantasised about what could happen if an industrial band ever got hold of someone who could really sing? If Throbbing Gristle hadn’t been pissing about when they promised us 20 Jazz Funk Greats? It’s nothing short of revelatory what a foil these noises make for a vocalist like Fisher – the R&B flourishes of ‘Chaka’, which rise against a chaotic backdrop of Cabs induced funk or the mounting, soulful fury of ‘Hour of the Furnaces’ – the tropes of industrial music haven’t sounded this plainly disorienting in a long time.

Amidst the confusion, however, there is nothing confused. There is No Year doesn’t let up for a moment. But where traditionally, industrial artists work hard to avoid sounding like musicians, there’s a surface slickness to Algiers music that belies the textures of the sounds they employ. They can make a sound that might be an aircraft engine dropped into a cement mixer and somehow make it pop. And things shift imperceptibly with each listen – you make a single step here or there and the light and the angle changes and find yourself confronted with a new illusion. Each time around it’s a different record.

Fisher culled the lyrics of There is No Year from his epic poem Misophonia, and I haven’t felt such a keen sense of rightness since I first heard about Bowie’s abortive Diamond Dogs musical, with its promise of roller-skating cockney space urchins and totalitarian balladry. There’s something both tantalising and warmly satisfying about the idea of a work of art, perhaps a greater work of art, barely glimpsed out of the corner of your imagination. Particularly if it sounds enormously mad. An epic poem? Yes, please. Can we somehow reverse engineer the epic Misophonia? Hint at what the muses sang to Algiers?

Misophonia is a condition that we might understand as fear of, or allergy to, sound itself. It’s a real thing, a kind of a response to aural stimuli that has been compared to dyslexia – and where people with dyslexia are often said have an excellent grasp of spatial relationships, and can make successful engineers or artists, so misophonia, with understanding and encouragement, is sometimes claimed to confer similar benefits on people who experience it. They can hear things we can’t, and it sometimes hurts.

The plot? It’s a story all about desire. There are lovers here, undoubtedly revolutionaries of some kind, surrounded by enemies and conspiracy. A world upside down, a society collapsing, burning. As well as desire, there is denial – indeed, we run up against denial more than once. ‘Hour of the Furnaces’ sounds like it could be right up in the face of Scott Morrison, or anyone else getting on with their business while the climate disintegrates around them. ‘Waiting for the Sound’ starts with the streets burning, and ends with our protagonist watching someone (an ally or lover?) turn away. There’s violence, a sensation of intense commotion that surges through the first act. The choir of voices in ‘Dispossession’ warn us, “You can’t run away”, but the world is ashes and shadows and soldiers and kings, and the freedom that’s coming might be a breakdown. The margins burn with anxiety. There are promises we mean to keep (“You’ll never be alone”) and the ever-present heat (“We all dance into the fire / La la la la”). It feels like betrayal is around every corner and in the tracks ‘Nothing Bloomed’ and ‘Losing is Ours’, a terrible engine overhead sounds like the end of hope itself.

‘Losing is Ours’. Ouch. Can’t disagree. Losing does seem to be ours. How prescient do you need to be to come up with this stuff? Like the Manic Street Preachers in their heyday, Algiers’ slightest gestures seem to imply that other bands really could put it a bit more effort. That they could read the papers now and then. Or visit a library. Algiers also share the Manic’s ability to make something intensely personal a question of global politics. Every love song is also always a protest song and it has always been thus, a fact that the music business tries constantly to obscure, even while it exploits it.

There is No Year is the music we need right now, fired up, political and anxious, staring the end of the world in the face, but not giving up. It’s the sound of a band who can hear things we can’t. Algiers have rediscovered Depeche Mode’s always present implication that any experience of desire or act of love, no matter how marginal, how strange, contains the seeds of revolution, of a better world. That desire can free all of us.